This was a busy week for me, as I did four talks in three days, over the course of visits to two different campuses, Catawba College and St. Anselm College.

The first visit was to

Catawba College in Salisbury, North Carolina. Salisbury is a little town north of Charlotte, and Catawba is a small college with about 1200 students. It’s always nice to visit North Carolina in March, as the trees are already blossoming into life.

The main event was a talk on

The Kite Runner, theoretically for the entire first-year class at the college. They put me up at an imposing guest house, which turned out to really be a small mansion decorated in fine southern style.

1. The talk on

The Kite Runner is called “The Authenticity of The Kite Runner and the Problem of Cultural Translation.” It is a souped-up version of a general interest talk I’ve been doing at other places over the past year or so. The version I gave in Portland last year was perhaps still a little sketchy; this version was much closer to a fully-baked talk.

The students, generally, seemed to like it. But there's one thing I’ve noticed -- when you give talks about authenticity, even if you’re

attacking the popular dependence on the concept of authenticity, people will wonder about your own ‘authenticity’ to speak. And every time I’ve talked about this, I’ve been asked something along the lines of “Are you an Afghan? Why are you doing this talk?”

On the one hand, as a literary critic I don’t feel any qualms whatsoever in saying, “well, I’ve studied it and thought about it, and that’s all the authority I need. Moreover, my point here is that authenticity is a value that readers cling to for the wrong reasons -– and insofar as they do cling to it, they’re probably going to be disappointed.” But even as I say that, I recognize that there is something to the idea that contemporary novelists are at their best when they’re writing about what they know, what they’ve personally lived through. (Interestingly, this wasn’t really true for writers like Dickens or Thackeray; perhaps “realism” has come to be defined in more exacting terms than it used to be.) Even if “authenticity” is a questionable concept for fiction, it is a concept that never entirely goes away. (Though it should still be said that the idea of an author's authenticity and a critic's connection to the subject she or he studies are two separate things.)

Critical authenticity or no, I am planning on rewriting this talk for one final time -- to turn it into a publishable (hopefully) essay –- on

Afghan Expatriate Narratives (which will include a discussion of Nelofer Pazira’s book and films, Said Hyder Akbar, Saira Shah, Farah Ahmedi, and perhaps a couple of others).

2. At the same college I guest-lectured in a class on

travel narratives, which was also fun. I could talk about my approach to teaching travel narratives at Lehigh, and build toward an argument that at the present moment of globalization it’s possible for writers to scramble the old codes and conventions of colonialist travel writing. As with much postcolonial literature in general, though, even as they aspire towards new forms, the legacy of the old forms is still in view. We’ve perhaps moved past the era of postcolonial revisions of colonialist classics (the

Wide Sargasso Sea moment, if you will), but not entirely left it behind. One can’t entirely forget the Joseph Conrads and the Katherine Mayos even as one reads new work by people like Rattawut Lapcharoensap, whose

Sightseeing is a form of ‘talking back’ to the conventions of western travel narratives, here with a focus on Thailand’s current status as a kind of sexual tourism destination.

I should also note that I enjoyed chatting with the faculty members I met at Catawba about diverse subjects, from the music Nitin Sawhney composed for the soundtrack of Mira Nair’s

Namesake, to Lehigh’s famous advocate of Intelligent Design, Michael Behe. Despite the presence of superstar figures in the International Relations department and a top-ranked engineering college, the name most strongly associated with Lehigh –- especially down in Billy Graham country –- is still Dr. Behe’s.

3. On Friday morning I got on another plane and headed to

St. Anselm College in Manchester, New Hampshire -– a state where the trees are still deep in winter mode, but the political season is fully in bloom. Here the college had arranged with a car service to take me to and from the college and a local hotel. And without exception, every driver I talked to had strong opinions on national politics, as well as specific political candidates. The college itself is also a bit of a political wonk’s paradise, which fairly regularly hosts debates amongst presidential candidates during the primaries.

John Edwards, apparently, had come through last year, and in the same building where I gave my talk on Saturday morning (the

New Hampshire Institute of Politics -– which has its own, in-house television studio), the New Hampshire Democratic Party was holding an internal election to determine its new leadership. Nearly every faculty member I talked to knew the names of the candidates for the internal leadership of the state Democratic Party. It’s a far cry from a state like Pennsylvania, where only hardcore wonks would really know the ins and outs of a political party’s internal structure.

Again, the main event was a talk on

The Kite Runner, this time for a group of about 25 faculty members. Strangely, the talk I gave to first-year students, with only a few adjustments, seemed to work just as well for faculty. (Though it helped considerably that the faculty members were from a number of different disciplines –- everything from chemistry to theology to criminal justice. A talk just for the English Department would have needed to be entirely re-written.)

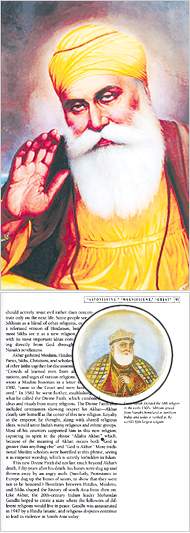

4. I also guest-lectured in a first-year composition class at St. Anselm. Here I was asked to talk about

Sikhism, beginning with the early period, and including a perspective on the Sikh experience in the U.S., up to and after 9/11. And, since this talk was sponsored by the English department, I was also asked to give a brief discussion of modern, secular Sikh literature -– people like Khushwant Singh, Shauna Singh Baldwin, Ajeet Cour, and Kartar Singh Duggal.

Partly because my training is in literature rather than religion per se, I tend to find it awkward to discuss Sikhism in academic settings. Even simple questions like “what is the significance of the turban?” end up requiring rather complicated, nuanced answers. (The Sikh turban, or dastaar, is a central symbol of Sikhism that isn’t actually named in the Guru Granth Sahib, or the ‘Five Ks’ laid down by Guru Gobind Singh.)

*

Over the course of these various travels, several of my flights into and out of Philadelphia were delayed -– usually for purely administrative reasons –- and I was struck to find how many passengers around me were ready to recite their various travel horror stories. It seems the plague of delayed flights, long lines, non-working self check-in kiosks, and worst of all, missed connections, has made travel misery a central fact of life for anyone flying into and out of Philadelphia in recent months. The mood of air travel has gotten pretty grim; it makes me extremely glad that I’m not in a field like Consulting, which requires almost constant travel. How long before the hordes of disgruntled passengers start rebelling?

*

And that’s it -- back to daily life, grading papers and changing diapers.

(Not that I equate the two activities, not in the least…)