There’s a great research- and reporting-driven opinion essay by Lydia Polgreen in the New York Times about how Indian Americans have found themselves flat-footed after the surge in anti-South Asian rhetoric and policy from the right. There are two prongs of this – one is the expansion of policies designed to reduce immigration, and the other being a more insidious cultural turn towards xenophobia and open, unapologetic racism.

The Trump administration, led by Trump himself but also J.D. Vance and Stephen Miller, has been dead-set on reducing both legal and illegal immigration from all non-European countries. The administration can apparently act on this single-handedly – virtually eliminating asylum options, adding onerous fees and paperwork to H-1B visa processes, and making it more difficult and less appealing for Indian students to come study in the U.S. (Indian student enrollment at U.S. universities was down 44% this year.) The good news is that at least some of that may be at least partially reversible the next time there’s a Democrat in the White House. Then again, it is certainly possible that future Democrats, having seen how unpopular Joe Biden’s approach to immigration was, may be reluctant to look “soft” on immigration and keep at least some of the Trump policies in place. (The ICE raids, we can hope, will stop once Trump is out of office.) Without comprehensive immigration reform, it is not clear there is a way to fix everything that’s been broken in the immigration system.

That leaves the racism; this is something we can fight, but first we have to understand it. Some right-wing Indian Americans have been surprised to discover the rapid acceleration of racialized hostility on social media. After encountering an overwhelming array of hostility to his benign Diwali post on social media (choice example: “Go back home and worship your sand demons”), Vivek Ramaswamy asked his peers on the right to “cut the identity politics.” Even Dinesh D’Souza, a commentator who built a long career on anti-Black race-baiting, has finally decided to be a little bit offended (“In a career spanning 40 years, I have never encountered this type of rhetoric. The Right never used to talk like this. So who on our side has legitimized this type of vile degradation?”) To these folks, I would absolutely say, you made your bed, now lie in it.

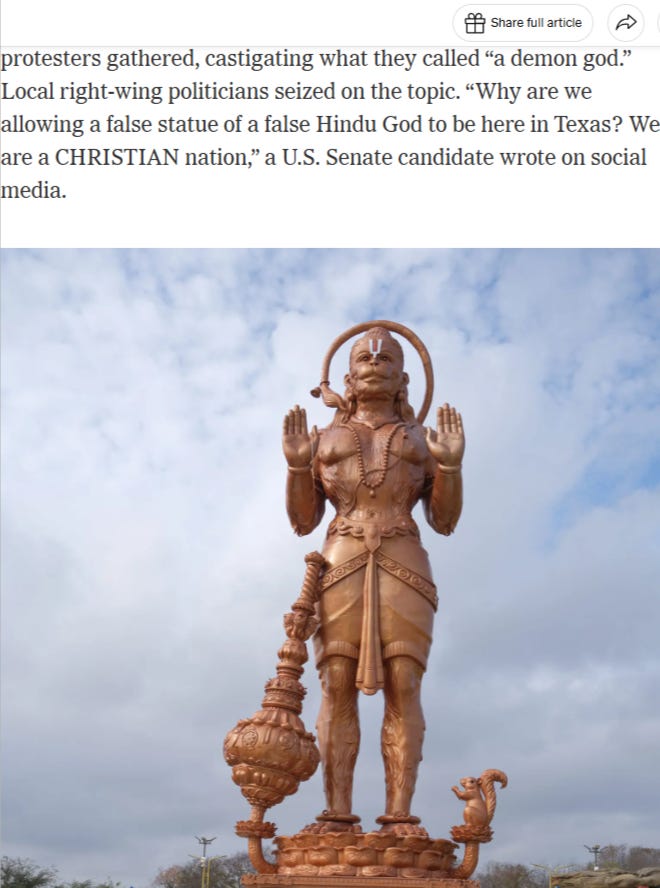

Others, like the retired doctor in Texas in Polgreen's story whose community built a 90 foot Hanuman statue at their local Mandir only to discover evangelical Christians in their town protesting at the temple gates, need to wake up to the new realities of American life. Below I have a couple of strategies for how South Asian Americans might toughen up a bit.

Some of what I have to say is hinted at in Polgreen’s piece itself. I would recommend reading through to the second half, where she has some helpful quotes from Suketu Mehta about the delusions some Indian Americans have harbored about how others really feel about them:

But Mehta also wondered whether Indian Americans had become a bit smug about their spectacular success in America over the past six decades, trusting that their wealth and status would shield them from the kind of bigotry that once barred them from entry and citizenship. Indian Americans, he said, tell themselves: “We are the richest, best educated people. We don’t commit crimes. We go to good schools. We came here legally. We’re not like the Mexicans.”

Mehta finds this exceptionalism both understandable and dangerous. The Indians who come to the United States are not just the most ambitious and educated. They also are mostly the beneficiaries of the durable hierarchies of caste, class and religion that stratify Indian life.

Following Mehta’s insightful comments above, it seems to me that the goal for South Asian Americans has to be to build generation-spanning institutions and spend both cultural capital as well as real capital on investments that benefit American society as a whole.

Nobody is impressed by “model minority” rhetoric, and some communities are actively hurt by it. A surprising number of South Asian Americans, especially of the older generation, blithely cite success statistics and low crime rates as if those all happened in a vacuum. And as if other communities haven’t been on the receiving end of generational institutional racism, cyclical poverty, and over-incarceration.

Nor is there much going to be much benefit in complaining about racism that mysteriously just appeared. Newsflash: it was always there; it’s just more visible now that there are politicians at the top who are willing to exploit it and mobilize it. The kinds of demonization that have been directed against Black folks and Latinos can also be directed against privileged brown immigrants. Indeed, it should not surprise us that this would happen.

So what can we do?

1. South Asian Americans could work together with other minoritized communities to fight anti-Black and anti-Latino racism, all forms of xenophobia, anti-Semitism, and anti-Muslim rhetoric wherever any of these may crop up. We need to learn to see those fights as our fights. (Note: this is why "South Asian American" – including immigrants from Muslim-majority South Asian countries as well as Nepal and Sri Lanka – is a better framework for organizing than “Indian American.”)

2. South Asian Americans could use our economic clout to build lobbying groups and PACs to advance South Asian community interests. If a politician running for the U.S. Senate starts posting about Hindu deities as “demons” on social media (as happened with the Hanuman statue in Texas), a strategic offer of a political donation if they can tone it down could do wonders. Otherwise, make a donation to their primary opponent and announce why we’re doing that to the media. Indian Americans have been happy to spend their money building massive, showy temples. In politics, they’ve been somewhat inclined to stay on the sidelines. It’s time for that to change.

3. South Asian Americans need to rally behind politicians who support South Asian communities -- and civil rights and secularism more generally -- and unify against those who don’t. Anyone who talks like Stephen Miller or J.D. Vance should not have a chance of getting our vote. I was not hugely surprised to see that in the 2024 election there was a small but noticeable shift in the Indian American community towards Trump – even at a time when Trump’s opponent was an Indian-American woman! (61% of Indian Americans still voted for Harris in 2024, but one might have expected that number to be higher.) Some of the interest in Trump, admittedly, was due to social media misinformation (see point #4 below), as well as the “economic message.” But some of the softness in support was due to lack of clarity and confusion about what the different parties actually stood for.

4. South Asian Americans probably need to invest in social media influence campaigns to correct falsehoods, misinformation, and out-of-context stories.

In conversations leading up to the 2024 campaign, a surprising number of my friends and acquaintances were citing an old story about Kamala Harris that had been circulating on social media about Kamala Harris’ role as Attorney General in a case in 2011, where a Sikh man with turban and beard sued to be able to hold a job as a prison guard, which requires people to be clean-shaven; Harris supported the state of California’s position on prison guards being clean-shaven to wear gas masks. This is apparently a real story, but it is hardly a reason to say that “Kamala Harris is anti-Sikh.” Again, if we were comparing Harris – a Black and South Asian candidate with a long history of supporting civil rights – to Trump, it should be clear to everyone who is likely more sympathetic to South Asian communities, including Sikh Americans.

Similarly, a number of my family members and friends were duped by the idea – again, popular on WhatsApp – that “Modi and Trump are best buddies, so nothing bad could happen with respect to India or Indians.” They seemed not to realize that Trump meant what he was saying on the campaign trail about radical changes to the immigration system, and what that might entail.

How exactly this might get fixed is not so easy. Some of it could be solved by the platforms themselves. But probably advocacy groups should be thinking about corrective social media influence campaigns to respond to out-of-context stories. These can be tricky to do well, but the incredible success of Zohran Mamdani on social media in the 2025 NYC mayoral campaign might be a model to emulate. Humor, wit, and charismatic messengers could go a long way here.