I'm sorry I've been a slack blogger of late -- I was finishing up another article for a journal, this time on blogging, anonymity, and the changing concept of "authorship." It would be a shame to neglect this blog just as I'm starting to write professionally about blogging!

*

At any rate, here's one recommendation: last week's Radio Open Source conversation with William Dalrymple. Many of the points Dalrymple makes will be familiar to people who have been following the reviews of his new book, The Last Mughal. (I blogged about it here)

What is new in this conversation is the attempt to make a direct parallel between the changing behavior of the British in the months and years leading up to the Mutiny, and the attitude of today's neo-conservative Hawks on the policy of "regime change" and "spreading democracy" around the Middle East.

The show was inspired by Ram Manikkalingam's excellent review of the book (along with Imperial Life in the Emerald City) up at 3 Quarks Daily.

Manan Ahmed, ("Sepoy" of Chapati Mystery -- highly appropriate to this topic) also makes an appearance in the last 20 minutes, talking about the work postcolonial historians have been trying to do to bring forward the kinds of stories Dalrymple's book focuses on.

The entire show is available for downloading as an MP3; if you are into downloading podcasts, this might be a good one. Otherwise, if you have 40 minutes, you might just want to listen to it right on the web.

Postcolonial/Global literature and film, Modernism, African American literature, and the Digital Humanities.

Four Talks in Three Days: North Carolina, New Hampshire

This was a busy week for me, as I did four talks in three days, over the course of visits to two different campuses, Catawba College and St. Anselm College.

The first visit was to Catawba College in Salisbury, North Carolina. Salisbury is a little town north of Charlotte, and Catawba is a small college with about 1200 students. It’s always nice to visit North Carolina in March, as the trees are already blossoming into life.

The main event was a talk on The Kite Runner, theoretically for the entire first-year class at the college. They put me up at an imposing guest house, which turned out to really be a small mansion decorated in fine southern style.

1. The talk on The Kite Runner is called “The Authenticity of The Kite Runner and the Problem of Cultural Translation.” It is a souped-up version of a general interest talk I’ve been doing at other places over the past year or so. The version I gave in Portland last year was perhaps still a little sketchy; this version was much closer to a fully-baked talk.

The students, generally, seemed to like it. But there's one thing I’ve noticed -- when you give talks about authenticity, even if you’re attacking the popular dependence on the concept of authenticity, people will wonder about your own ‘authenticity’ to speak. And every time I’ve talked about this, I’ve been asked something along the lines of “Are you an Afghan? Why are you doing this talk?”

On the one hand, as a literary critic I don’t feel any qualms whatsoever in saying, “well, I’ve studied it and thought about it, and that’s all the authority I need. Moreover, my point here is that authenticity is a value that readers cling to for the wrong reasons -– and insofar as they do cling to it, they’re probably going to be disappointed.” But even as I say that, I recognize that there is something to the idea that contemporary novelists are at their best when they’re writing about what they know, what they’ve personally lived through. (Interestingly, this wasn’t really true for writers like Dickens or Thackeray; perhaps “realism” has come to be defined in more exacting terms than it used to be.) Even if “authenticity” is a questionable concept for fiction, it is a concept that never entirely goes away. (Though it should still be said that the idea of an author's authenticity and a critic's connection to the subject she or he studies are two separate things.)

Critical authenticity or no, I am planning on rewriting this talk for one final time -- to turn it into a publishable (hopefully) essay –- on Afghan Expatriate Narratives (which will include a discussion of Nelofer Pazira’s book and films, Said Hyder Akbar, Saira Shah, Farah Ahmedi, and perhaps a couple of others).

2. At the same college I guest-lectured in a class on travel narratives, which was also fun. I could talk about my approach to teaching travel narratives at Lehigh, and build toward an argument that at the present moment of globalization it’s possible for writers to scramble the old codes and conventions of colonialist travel writing. As with much postcolonial literature in general, though, even as they aspire towards new forms, the legacy of the old forms is still in view. We’ve perhaps moved past the era of postcolonial revisions of colonialist classics (the Wide Sargasso Sea moment, if you will), but not entirely left it behind. One can’t entirely forget the Joseph Conrads and the Katherine Mayos even as one reads new work by people like Rattawut Lapcharoensap, whose Sightseeing is a form of ‘talking back’ to the conventions of western travel narratives, here with a focus on Thailand’s current status as a kind of sexual tourism destination.

I should also note that I enjoyed chatting with the faculty members I met at Catawba about diverse subjects, from the music Nitin Sawhney composed for the soundtrack of Mira Nair’s Namesake, to Lehigh’s famous advocate of Intelligent Design, Michael Behe. Despite the presence of superstar figures in the International Relations department and a top-ranked engineering college, the name most strongly associated with Lehigh –- especially down in Billy Graham country –- is still Dr. Behe’s.

3. On Friday morning I got on another plane and headed to St. Anselm College in Manchester, New Hampshire -– a state where the trees are still deep in winter mode, but the political season is fully in bloom. Here the college had arranged with a car service to take me to and from the college and a local hotel. And without exception, every driver I talked to had strong opinions on national politics, as well as specific political candidates. The college itself is also a bit of a political wonk’s paradise, which fairly regularly hosts debates amongst presidential candidates during the primaries. John Edwards, apparently, had come through last year, and in the same building where I gave my talk on Saturday morning (the New Hampshire Institute of Politics -– which has its own, in-house television studio), the New Hampshire Democratic Party was holding an internal election to determine its new leadership. Nearly every faculty member I talked to knew the names of the candidates for the internal leadership of the state Democratic Party. It’s a far cry from a state like Pennsylvania, where only hardcore wonks would really know the ins and outs of a political party’s internal structure.

Again, the main event was a talk on The Kite Runner, this time for a group of about 25 faculty members. Strangely, the talk I gave to first-year students, with only a few adjustments, seemed to work just as well for faculty. (Though it helped considerably that the faculty members were from a number of different disciplines –- everything from chemistry to theology to criminal justice. A talk just for the English Department would have needed to be entirely re-written.)

4. I also guest-lectured in a first-year composition class at St. Anselm. Here I was asked to talk about Sikhism, beginning with the early period, and including a perspective on the Sikh experience in the U.S., up to and after 9/11. And, since this talk was sponsored by the English department, I was also asked to give a brief discussion of modern, secular Sikh literature -– people like Khushwant Singh, Shauna Singh Baldwin, Ajeet Cour, and Kartar Singh Duggal.

Partly because my training is in literature rather than religion per se, I tend to find it awkward to discuss Sikhism in academic settings. Even simple questions like “what is the significance of the turban?” end up requiring rather complicated, nuanced answers. (The Sikh turban, or dastaar, is a central symbol of Sikhism that isn’t actually named in the Guru Granth Sahib, or the ‘Five Ks’ laid down by Guru Gobind Singh.)

*

Over the course of these various travels, several of my flights into and out of Philadelphia were delayed -– usually for purely administrative reasons –- and I was struck to find how many passengers around me were ready to recite their various travel horror stories. It seems the plague of delayed flights, long lines, non-working self check-in kiosks, and worst of all, missed connections, has made travel misery a central fact of life for anyone flying into and out of Philadelphia in recent months. The mood of air travel has gotten pretty grim; it makes me extremely glad that I’m not in a field like Consulting, which requires almost constant travel. How long before the hordes of disgruntled passengers start rebelling?

*

And that’s it -- back to daily life, grading papers and changing diapers.

(Not that I equate the two activities, not in the least…)

The first visit was to Catawba College in Salisbury, North Carolina. Salisbury is a little town north of Charlotte, and Catawba is a small college with about 1200 students. It’s always nice to visit North Carolina in March, as the trees are already blossoming into life.

The main event was a talk on The Kite Runner, theoretically for the entire first-year class at the college. They put me up at an imposing guest house, which turned out to really be a small mansion decorated in fine southern style.

1. The talk on The Kite Runner is called “The Authenticity of The Kite Runner and the Problem of Cultural Translation.” It is a souped-up version of a general interest talk I’ve been doing at other places over the past year or so. The version I gave in Portland last year was perhaps still a little sketchy; this version was much closer to a fully-baked talk.

The students, generally, seemed to like it. But there's one thing I’ve noticed -- when you give talks about authenticity, even if you’re attacking the popular dependence on the concept of authenticity, people will wonder about your own ‘authenticity’ to speak. And every time I’ve talked about this, I’ve been asked something along the lines of “Are you an Afghan? Why are you doing this talk?”

On the one hand, as a literary critic I don’t feel any qualms whatsoever in saying, “well, I’ve studied it and thought about it, and that’s all the authority I need. Moreover, my point here is that authenticity is a value that readers cling to for the wrong reasons -– and insofar as they do cling to it, they’re probably going to be disappointed.” But even as I say that, I recognize that there is something to the idea that contemporary novelists are at their best when they’re writing about what they know, what they’ve personally lived through. (Interestingly, this wasn’t really true for writers like Dickens or Thackeray; perhaps “realism” has come to be defined in more exacting terms than it used to be.) Even if “authenticity” is a questionable concept for fiction, it is a concept that never entirely goes away. (Though it should still be said that the idea of an author's authenticity and a critic's connection to the subject she or he studies are two separate things.)

Critical authenticity or no, I am planning on rewriting this talk for one final time -- to turn it into a publishable (hopefully) essay –- on Afghan Expatriate Narratives (which will include a discussion of Nelofer Pazira’s book and films, Said Hyder Akbar, Saira Shah, Farah Ahmedi, and perhaps a couple of others).

2. At the same college I guest-lectured in a class on travel narratives, which was also fun. I could talk about my approach to teaching travel narratives at Lehigh, and build toward an argument that at the present moment of globalization it’s possible for writers to scramble the old codes and conventions of colonialist travel writing. As with much postcolonial literature in general, though, even as they aspire towards new forms, the legacy of the old forms is still in view. We’ve perhaps moved past the era of postcolonial revisions of colonialist classics (the Wide Sargasso Sea moment, if you will), but not entirely left it behind. One can’t entirely forget the Joseph Conrads and the Katherine Mayos even as one reads new work by people like Rattawut Lapcharoensap, whose Sightseeing is a form of ‘talking back’ to the conventions of western travel narratives, here with a focus on Thailand’s current status as a kind of sexual tourism destination.

I should also note that I enjoyed chatting with the faculty members I met at Catawba about diverse subjects, from the music Nitin Sawhney composed for the soundtrack of Mira Nair’s Namesake, to Lehigh’s famous advocate of Intelligent Design, Michael Behe. Despite the presence of superstar figures in the International Relations department and a top-ranked engineering college, the name most strongly associated with Lehigh –- especially down in Billy Graham country –- is still Dr. Behe’s.

3. On Friday morning I got on another plane and headed to St. Anselm College in Manchester, New Hampshire -– a state where the trees are still deep in winter mode, but the political season is fully in bloom. Here the college had arranged with a car service to take me to and from the college and a local hotel. And without exception, every driver I talked to had strong opinions on national politics, as well as specific political candidates. The college itself is also a bit of a political wonk’s paradise, which fairly regularly hosts debates amongst presidential candidates during the primaries. John Edwards, apparently, had come through last year, and in the same building where I gave my talk on Saturday morning (the New Hampshire Institute of Politics -– which has its own, in-house television studio), the New Hampshire Democratic Party was holding an internal election to determine its new leadership. Nearly every faculty member I talked to knew the names of the candidates for the internal leadership of the state Democratic Party. It’s a far cry from a state like Pennsylvania, where only hardcore wonks would really know the ins and outs of a political party’s internal structure.

Again, the main event was a talk on The Kite Runner, this time for a group of about 25 faculty members. Strangely, the talk I gave to first-year students, with only a few adjustments, seemed to work just as well for faculty. (Though it helped considerably that the faculty members were from a number of different disciplines –- everything from chemistry to theology to criminal justice. A talk just for the English Department would have needed to be entirely re-written.)

4. I also guest-lectured in a first-year composition class at St. Anselm. Here I was asked to talk about Sikhism, beginning with the early period, and including a perspective on the Sikh experience in the U.S., up to and after 9/11. And, since this talk was sponsored by the English department, I was also asked to give a brief discussion of modern, secular Sikh literature -– people like Khushwant Singh, Shauna Singh Baldwin, Ajeet Cour, and Kartar Singh Duggal.

Partly because my training is in literature rather than religion per se, I tend to find it awkward to discuss Sikhism in academic settings. Even simple questions like “what is the significance of the turban?” end up requiring rather complicated, nuanced answers. (The Sikh turban, or dastaar, is a central symbol of Sikhism that isn’t actually named in the Guru Granth Sahib, or the ‘Five Ks’ laid down by Guru Gobind Singh.)

*

Over the course of these various travels, several of my flights into and out of Philadelphia were delayed -– usually for purely administrative reasons –- and I was struck to find how many passengers around me were ready to recite their various travel horror stories. It seems the plague of delayed flights, long lines, non-working self check-in kiosks, and worst of all, missed connections, has made travel misery a central fact of life for anyone flying into and out of Philadelphia in recent months. The mood of air travel has gotten pretty grim; it makes me extremely glad that I’m not in a field like Consulting, which requires almost constant travel. How long before the hordes of disgruntled passengers start rebelling?

*

And that’s it -- back to daily life, grading papers and changing diapers.

(Not that I equate the two activities, not in the least…)

Labels:

Afghanistan,

KiteRunner,

Me,

Sikhism,

TravelNarratives,

Travels

The Namesake

When you have a five-month old at home, you watch most of your films on DVD.

This weekend, though, we were able to arrange in-family babysitting (thanks, Abhit) so we could go see The Namesake.

We enjoyed it. I don't have too much to add to what Cicatrix and Sajit have already said at Sepia Mutiny, except that it makes sense to shift the center of the story from Gogol to his parents, as Nair does. For one thing, it fits Mira Nair's profile a bit more: she herself is a first-generation immigrant and parent whose kids grew up primarily in the U.S. (Indeed, she talks about how she only heard about the actor Kal Penn through her children, who had watched Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle.) But possibly the greater emphasis on Ashoke and Ashima also just makes the story more broadly appealing -- and it certainly doesn't hurt to have really talented actors playing the parents. Tabu and Irfan Khan are both terrific; they've left bollywood far behind in this film.

As for the commercial prospects of The Namesake, I'm not sure. I do think it could be pretty broadly appealing, though it's not quite as much fun as Nair's own earlier hit, Monsoon Wedding, nor does it have the same warm and fuzzy vibe of Gurinder Chadha's crossover, Bend it Like Beckham. The Namesake is great, but in my view it is more strictly an art film.

*

See my earlier comments on Jhumpa Lahiri's book, The Namesake, here.

This weekend, though, we were able to arrange in-family babysitting (thanks, Abhit) so we could go see The Namesake.

We enjoyed it. I don't have too much to add to what Cicatrix and Sajit have already said at Sepia Mutiny, except that it makes sense to shift the center of the story from Gogol to his parents, as Nair does. For one thing, it fits Mira Nair's profile a bit more: she herself is a first-generation immigrant and parent whose kids grew up primarily in the U.S. (Indeed, she talks about how she only heard about the actor Kal Penn through her children, who had watched Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle.) But possibly the greater emphasis on Ashoke and Ashima also just makes the story more broadly appealing -- and it certainly doesn't hurt to have really talented actors playing the parents. Tabu and Irfan Khan are both terrific; they've left bollywood far behind in this film.

As for the commercial prospects of The Namesake, I'm not sure. I do think it could be pretty broadly appealing, though it's not quite as much fun as Nair's own earlier hit, Monsoon Wedding, nor does it have the same warm and fuzzy vibe of Gurinder Chadha's crossover, Bend it Like Beckham. The Namesake is great, but in my view it is more strictly an art film.

*

See my earlier comments on Jhumpa Lahiri's book, The Namesake, here.

"The Cow" -- a Sufi Joke

I came across the following in Idries Shah’s Wisdom of the Idiots (Octagon Press, 1970). Idries Shah is an Afghan writer who emigrated to England in the late 1960s and early 1970s. He wrote several books, and was a kind of ambassador of Sufi philosophy in the west (his daughter is Saira Shah, a journalist, and the author of The Storyteller's Daughter). This collection contains a series of short Sufi anecdotes and sayings, some of them almost joke-like.

The present-day relevance of this story is:

a) Clearly, the cow is America's desire to spread democracy, and the milk is democracy itself.

b) Clearly, the cow is Pervez Musharraf's commitment to fight terrorism, and the milk is Al Qaeda.

c) There is no relevance, but did you hear the funny story about the cow in West Bengal who eats chicken?

d) Readers, please fill in the blank. What could the relevance of this story be?

The Cow

Once upon a time there was a cow. In all the world there was no animal which so regularly gave so much milk of such high quality.

People came from far and wide to see this wonder. The cow was extolled by all. Fathers told their children of its dedication to its appointed task. Ministers of religion adjured their flocks to emulate it in their own way. Government officials referred to it as a paragon which right behaviour, planning and thinking could duplicate in the human community. Everyone was, in short, able to benefit from the existence of this wonderful animal.

There was, however, one feature which most people, absorbed as they were by the obvious advantages of the cow, failed to observe. It had a little habit, you see. And this habit was that, as soon as a pail had been filled with its admittedly unparalleled milk – it kicked it over.

The present-day relevance of this story is:

a) Clearly, the cow is America's desire to spread democracy, and the milk is democracy itself.

b) Clearly, the cow is Pervez Musharraf's commitment to fight terrorism, and the milk is Al Qaeda.

c) There is no relevance, but did you hear the funny story about the cow in West Bengal who eats chicken?

d) Readers, please fill in the blank. What could the relevance of this story be?

Two Passages Briefly Compared: "Ulysses" and "To the Lighthouse"

This spring I'm teaching a course on Modernism, and I have many things I've been hoping to post about.

One topic we discussed might be described as "comparative stream of consciousness," though I generally don't emphasize the term "stream-of-consciousness" very much, since it is virtually impossible to define satisfactorily. In-class, I gave students two passages relating to the sea, one from Joyce's Ulysses, and the other from Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse.

Here's a passage from the end of Section I of Joyce's Ulysses ("Telemachus"):

Joyce caresses the music of the "wh" sound; this is virtually poetry. (Incidentally, at the end there, Stephen is beginning to remember the death of his mother.)

And here’s Woolf’s To the Lighthouse:

This comes from near the end of To the Lighthouse, after Mrs. Ramsay's death. Lily has been working on her painting near the Ramsay's summer house, while Mr. Ramsay, Cam, and James have gone on a day-trip to a lighthouse that is distant, but visible from where Lily sits. Augustus Carmichael has remained on shore with her, and figures here as the "very old man who had gone past her silently."

Both Woolf and Joyce aim to find meanings and moods in the landscape that are psychic rather than objectively descriptive. Both short passages also contain some kind of emotional or subjective turn, leading to a question ("Where now?"/"Where are they now?") But the two passages also show important differences in Woolf's and Joyce's respective styles, along the lines of sentence structure, theme, and sound of the prose.

Both Woolf and Joyce trade in moods, animating nature with reflections of human emotion. But Woolf's aim is to create a singular image (a "fabric") of grandeur, while Joyce seems more interested in doublings, pairings, and rhythm. Woolf meditates on the disappearance of the other through distance, while Joyce weaves the music of spoken language with the sound of water: "wavewhite wedded words shimmering on the dim tide."

Other interpretations? Are there parallels (or telling dissimilarities) I've missed?

One topic we discussed might be described as "comparative stream of consciousness," though I generally don't emphasize the term "stream-of-consciousness" very much, since it is virtually impossible to define satisfactorily. In-class, I gave students two passages relating to the sea, one from Joyce's Ulysses, and the other from Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse.

Here's a passage from the end of Section I of Joyce's Ulysses ("Telemachus"):

Woodshadows floated silently by through the morning peace from the stairhead seaward where he gazed. Inshore and farther out the mirror of water whitened, spurned by lightshod hurrying feet. White breast of the dim sea. The twining stresses, two by two. A hand plucking the harpstrings, merging their twining chords. Wavewhite wedded words shimmering on the dim tide.

A cloud began to cover the sun slowly, wholly, shadowing the bay in deeper green. It lay beneath him, a bowl of bitter waters. Fergus’ song: I sang it alone in the house, holding down the long dark chords. Her door was open: she wanted to hear my music. Silent with awe and pity I went to her bedside. She was crying in her wretched bed. For those words, Stephen: love’s bitter mystery.

Where now?

Joyce caresses the music of the "wh" sound; this is virtually poetry. (Incidentally, at the end there, Stephen is beginning to remember the death of his mother.)

And here’s Woolf’s To the Lighthouse:

So fine was the morning except for a streak of wind here and there that the sea and sky looked all one fabric, as if sails were stuck high up in the sky, or the clouds had dropped down into the sea. A steamer far out at sea had drawn in the air a great scroll of smoke which stayed there curving and circling decoratively, as if the air were a fine gauze which held things and kept them softly in its mesh, only gently swaying them this way and that. And as happens sometimes when the weather is very fine, the cliffs looked as if they were conscious of the cliffs, as if they signaled to each other some message of their own. For sometimes quite close to the shore, the Lighthouse looked this morning in the haze an enormous distance away.

‘Where are they now?’ Lily thought, looking out to sea. Where was he, that very old man who had gone past her silently, holding a brown paper parcel under his arm? The boat was in the middle of the bay.

This comes from near the end of To the Lighthouse, after Mrs. Ramsay's death. Lily has been working on her painting near the Ramsay's summer house, while Mr. Ramsay, Cam, and James have gone on a day-trip to a lighthouse that is distant, but visible from where Lily sits. Augustus Carmichael has remained on shore with her, and figures here as the "very old man who had gone past her silently."

Both Woolf and Joyce aim to find meanings and moods in the landscape that are psychic rather than objectively descriptive. Both short passages also contain some kind of emotional or subjective turn, leading to a question ("Where now?"/"Where are they now?") But the two passages also show important differences in Woolf's and Joyce's respective styles, along the lines of sentence structure, theme, and sound of the prose.

Both Woolf and Joyce trade in moods, animating nature with reflections of human emotion. But Woolf's aim is to create a singular image (a "fabric") of grandeur, while Joyce seems more interested in doublings, pairings, and rhythm. Woolf meditates on the disappearance of the other through distance, while Joyce weaves the music of spoken language with the sound of water: "wavewhite wedded words shimmering on the dim tide."

Other interpretations? Are there parallels (or telling dissimilarities) I've missed?

What did Guru Nanak look like? Textbooks in California

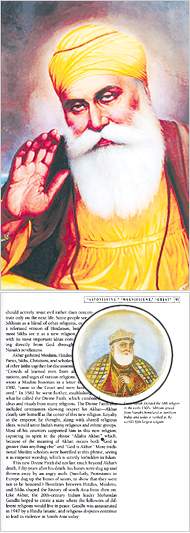

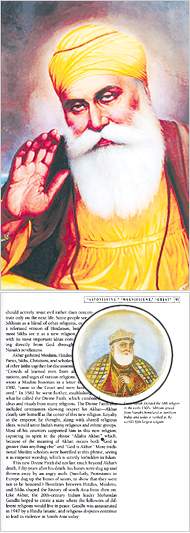

In California, the Times reports that the School Board unanimously voted last week to alter a seventh grade textbook image relating to Guru Nanak, the founder of the Sikh religion (or panth), after protests from the Sikh community.

The controversial image isn't the big one pictured, but the small one (I've added a circle to make it clearer). The image is a 19th century painting of Guru Nanak wearing a crown and what looks like a somewhat cropped beard. Both the crown and the beard shape are troubling to Sikhs, who are accustomed to seeing images of Guru Nanak more along the lines of the bigger image to the right -- flowing white beard, and humble attire.

Though the New York Times has good interviews with community members on this, the Contra Costa Times actually spells out the issue more clearly:

All of this raises the question -- what, in fact, did Guru Nanak look like? We don't have any images from his lifetime, and the later ones are clearly products of the values of their eras. What, historically, do we actually know? I went to Navtej Sarna's recent book, The Book of Nanak, to see what I could find out.

First off, I would recommend Navtej Sarna's book -- it's part of a series Penguin is doing, that also includes The Book of Mohammed. It's short, but it's well-written and accessible.

Secondly, Sarna states the obvious problem with any historical account of Guru Nanak: we don't have official (as in modernized, chronological) histories to work with, but rather a series of Janamsakhis, some of which were written down shortly after Guru Nanak's lifetime by personal associates, while others were written down a bit later -- at two or three degrees of separation. Some of the relevant manuscripts are mentioned, sketchily, at the Wikipedia site for Janamsakhis. (This Wikipedia entry could be improved!)

Some professional historians simply opt out of saying anything concrete about Guru Nanak's life. J.S. Grewal, for instance, in The Sikhs of the Punjab, goes right into textual analysis of passages from the Adi Granth, and doesn't mention any Janamsakhis. Sarna, for his part, acknowledges that his own work is based on the Janamsakhi materials, and proceeds on the basis that some of what is described is factual, while some must be under the category of folklore, and educated guesses have to be made. Along those lines, he comes up with a surprising description of Guru Nanak's attire:

Unfortunately, Sarna does not tell us which Janamsakhi this derives from -- and I'm sure people would be interested to know, since this is a bit different from the common image of Guru Nanak. Sarna does later mention that at the end of his travels, Guru Nanak gave up these "travel clothes" and adopted the ordinary dress of a "householder."

At every point, however, what's emphasized is the strength of Guru Nanak's personal humility and his rejection of personal wealth or political power (which is not the same as a rejection of the material world). So the crown that's pictured in the first version of the California textbook is certainly incorrect. The rest, however, is probably open to conjecture and argument.

*

One other thought: this controversy is obviously part of a new pattern of textbook contestation in California. An earlier chapter occurred last year, when the Hindu Education Foundation and the Vedic Foundation wrote long reports offering their criticisms and suggestions of the representation of Hinduism in California school textbooks. In a post on the subject, I reviewed the details of those reports, and came to feel that some were good suggestions, while others seemed to be cases of whitewashing history. Though some of the dynamics are similar, this is a very different (and indeed, much simpler) case.

The controversial image isn't the big one pictured, but the small one (I've added a circle to make it clearer). The image is a 19th century painting of Guru Nanak wearing a crown and what looks like a somewhat cropped beard. Both the crown and the beard shape are troubling to Sikhs, who are accustomed to seeing images of Guru Nanak more along the lines of the bigger image to the right -- flowing white beard, and humble attire.

Though the New York Times has good interviews with community members on this, the Contra Costa Times actually spells out the issue more clearly:

The image is taken from a 19th-century painting made after Muslims ruled India. The publisher used it because it complies with the company's policy of using only historical images in historical texts, said Tom Adams, director of curriculum for the Department of Education.

After Sikhs complained that the picture more closely reflected a Muslim man than a Sikh, Oxford offered to substitute it with an 18th-century portrait showing Guru Nanak with a red hat and trimmed beard. But Sikhs said that picture made their founder look like a Hindu.

The publisher now wants to scrap the picture entirely from the textbook, which was approved for use in California classrooms in 2005. There are about 250,000 Sikhs in California.

Sikh leaders say they want a new, more representative image of Guru Nanak, similar to the ones they place in Sikh temples and in their homes. The publisher has rejected those images as historically inaccurate. No images exist from the founder's lifetime, 1469 to 1538. (link)

All of this raises the question -- what, in fact, did Guru Nanak look like? We don't have any images from his lifetime, and the later ones are clearly products of the values of their eras. What, historically, do we actually know? I went to Navtej Sarna's recent book, The Book of Nanak, to see what I could find out.

First off, I would recommend Navtej Sarna's book -- it's part of a series Penguin is doing, that also includes The Book of Mohammed. It's short, but it's well-written and accessible.

Secondly, Sarna states the obvious problem with any historical account of Guru Nanak: we don't have official (as in modernized, chronological) histories to work with, but rather a series of Janamsakhis, some of which were written down shortly after Guru Nanak's lifetime by personal associates, while others were written down a bit later -- at two or three degrees of separation. Some of the relevant manuscripts are mentioned, sketchily, at the Wikipedia site for Janamsakhis. (This Wikipedia entry could be improved!)

Some professional historians simply opt out of saying anything concrete about Guru Nanak's life. J.S. Grewal, for instance, in The Sikhs of the Punjab, goes right into textual analysis of passages from the Adi Granth, and doesn't mention any Janamsakhis. Sarna, for his part, acknowledges that his own work is based on the Janamsakhi materials, and proceeds on the basis that some of what is described is factual, while some must be under the category of folklore, and educated guesses have to be made. Along those lines, he comes up with a surprising description of Guru Nanak's attire:

Nanak was accompanied by Mardana on his travels, who carried his rabab. He dressed in strange clothes that could not be identified with any sect and symbolized the universality of his mesage. He wore the long, loose shirt of a Muslim dervish but in the brownish red colour of the Hindu sanyasi. Around his waist he wore a white kafni or cloth belt like a faqir. A flat, short truban partly covered a Qalandar's cap on his head in the manner of Sufi wanderers. On his feet, he wore wooden sandals, each of a different design and colour. Sometimes, it is said, he wore a necklace of bones around his neck. (53-54)

Unfortunately, Sarna does not tell us which Janamsakhi this derives from -- and I'm sure people would be interested to know, since this is a bit different from the common image of Guru Nanak. Sarna does later mention that at the end of his travels, Guru Nanak gave up these "travel clothes" and adopted the ordinary dress of a "householder."

At every point, however, what's emphasized is the strength of Guru Nanak's personal humility and his rejection of personal wealth or political power (which is not the same as a rejection of the material world). So the crown that's pictured in the first version of the California textbook is certainly incorrect. The rest, however, is probably open to conjecture and argument.

*

One other thought: this controversy is obviously part of a new pattern of textbook contestation in California. An earlier chapter occurred last year, when the Hindu Education Foundation and the Vedic Foundation wrote long reports offering their criticisms and suggestions of the representation of Hinduism in California school textbooks. In a post on the subject, I reviewed the details of those reports, and came to feel that some were good suggestions, while others seemed to be cases of whitewashing history. Though some of the dynamics are similar, this is a very different (and indeed, much simpler) case.

Magic Realism on TV: "Heroes" vs. "Midnight's Children"

Am I the first person to think of shows like Lost and Heroes as the television equivalent of "magic realism" in the novel? These shows have elements of science fiction and fantasy, but remain grounded in realistic narration and human relationships. As a result, they can achieve mainstream respectability and broad popularity, while true Sci-Fi remains somewhat of a smaller, niche market.

This is going to sound blasphemous, but Heroes in particular actually reminds me a little of Midnight's Children in some ways. Remember this passage from Rushdie's novel:

Ah, Rushdie: the old passages don't disappoint. Of course, the different magical powers don't map precisely to the characters in Heroes, but there are certain overlaps:

Mohinder Suresh, oddly enough, resembles Saleem Sinai, in that he is the person who ties it all together. And Cihlar, as the villain, resembles Rushdie's Siva. Perhaps Clair Bennett as Parvati-the-Witch? Niki Sanders as a less villainous "Widow"?

I'm not saying the quality of the show could be compared, even remotely, to Rushdie's novel. It's more the idea of a large group of people who have supernatural gifts whose broader function isn't entirely clear. In Rushdie's novel, it becomes clear that the disintegration of the M.C.C. is a metaphor for the challenges to Indian nationalism -- and Saleem Sinai's special humiliation might be the humiliation of the first generation of India's ruling elite. But what social or political message is Heroes trying to convey? It hasn't become clear yet.

This is going to sound blasphemous, but Heroes in particular actually reminds me a little of Midnight's Children in some ways. Remember this passage from Rushdie's novel:

From Kerala, a boy who had the ability of stepping into mirrors and re-emerging through any surface in the land--through lakes, and (with greater difficulty), the polished bodies of automobiles . . . and a Goanese girl with the gift of multiplying fish . . . and children with powers of transformation: a werewolf from the Nilgiri hills, and from the great watershed of the Vindhvas, a boy who could increase or reduce his size at will, and had already (mischievously) been the cause of wild panic and rumors of the return of Giants . . . from Kashmir, there was a blue-eyed child of whose sex I was never certain, since by immersing herself in water he (or she) could alter it as she (or he) pleased. Some of us called this child Narada, others Markandaya, depending on which old fairy story of sexual change we had heard . . . near Jalna in the heart of the parched Deccan I found a water-divining youth, and at Budge-Budge outside of Calcutta a sharp-tongued girl whose words already had the power of inflicting physical wounds, so that after a few adults had found themselves bleeding freely as a result from some barb flung casually from her lips, they decided to lock her up in a bamboo cage and float her off down the Ganges to the Sunderbans jungles (which are the rightful home of monsters and phantasms); but nobody dared approach her, and she moved through the town surrounded by a vacuum of fear; nobody had the courage to deny her food. There was a boy who could eat metal and a girl whose fingers were so green that she could grow prize aubergines in the Thar desert; and more and more...

Ah, Rushdie: the old passages don't disappoint. Of course, the different magical powers don't map precisely to the characters in Heroes, but there are certain overlaps:

Claire Bennet (Hayden Panettiere), Mr. Bennet's adopted daughter, who lives in Odessa, Texas, and has a healing factor.

Simone Deveaux (Tawny Cypress), an art dealer and gallery owner whose skepticism and complicated romantic life are tested. She was killed by Isaac, who was trying to kill Peter and hit the wrong target.

D.L. Hawkins (Leonard Roberts), Once an escaped criminal, he has the power to alter his physical tangibility and phase through solid objects, both inanimate and organic.

Isaac Mendez (Santiago Cabrera), An artist living in New York who can paint future events during precognitive trances. He also writes and draws a comic book called 9th Wonders! which has also been shown to depict the future.

Hiro Nakamura (Masi Oka), A programmer[7] from Tokyo with the ability to manipulate the space-time continuum.

Matt Parkman (Greg Grunberg), A Los Angeles police officer with the ability to hear other people's thoughts.

Nathan Petrelli (Adrian Pasdar), a New York Congressional candidate with the ability of self-propelled flight. He is Claire Bennet's biological father.

Peter Petrelli (Milo Ventimiglia), A former hospice nurse and Nathan's younger brother. He is an empath with the ability to absorb the powers of others he has been near and can recall any ability he has used in the past by focusing on his feelings for those from whom the abilities originate. He has shown that he is capable of manifesting multiple abilities simultaneously.

Micah Sanders (Noah Gray-Cabey), D.L. and Niki's son and a child prodigy, Micah is a technopath, allowing him control of electrical signals, which gives him control of machines and electronic devices.

Niki Sanders (Ali Larter), The wife of D.L. and mother of Micah. A former internet stripper from Las Vegas who exhibits superhuman strength when her alternate personality, Jessica, surfaces.

Mohinder Suresh (Sendhil Ramamurthy), A genetics professor from India who travels to New York to investigate the death of his father, Chandra. Through his investigations, he comes into contact with people his father listed as possessing superhuman abilities. link

Mohinder Suresh, oddly enough, resembles Saleem Sinai, in that he is the person who ties it all together. And Cihlar, as the villain, resembles Rushdie's Siva. Perhaps Clair Bennett as Parvati-the-Witch? Niki Sanders as a less villainous "Widow"?

I'm not saying the quality of the show could be compared, even remotely, to Rushdie's novel. It's more the idea of a large group of people who have supernatural gifts whose broader function isn't entirely clear. In Rushdie's novel, it becomes clear that the disintegration of the M.C.C. is a metaphor for the challenges to Indian nationalism -- and Saleem Sinai's special humiliation might be the humiliation of the first generation of India's ruling elite. But what social or political message is Heroes trying to convey? It hasn't become clear yet.

Problems with Google Docs

You may be wondering where I've been. I've been working on some essays, most recently on E.M. Forster. That's about done, but now I have two more essays to write by April 1 -- one on the State of Postcolonial Theory, and the second being a revised/extended version of my MLA talk last December.

Shockingly, I've noticed that not blogging is sometimes correlated to getting more writing done. Amongst friends and colleagues, I've often argued that this actually isn't the case, that blogging and writing/publishing can in fact be fully complementary. At least for right now, for me, less blogging seems to mean more scholarly productivity. (I might yet change my mind, especially with the onset of Spring Break next week).

* * *

On my non-teaching days I've been doing research at the Van Pelt library at the University of Pennsylvania. I generally don't carry my laptop (it's both heavy and fragile), and for the most part that's not an issue, since most of one's time at the library is spent finding books and articles, photocopying them, and reading them. However, if you actually want to write at a computer, you have to use their public terminals. Some university library terminals have MS Word, but many times you just get a bare-bones Web browser.

But if you have Google, who needs MS Word anyways, right? Haven't we entered the golden age of "all you need is a browser"? (Wrong. And, No.)

For my session this past Monday, I uploaded my Word Docs to Google Docs to get around the public terminal problem. I then spent a couple of hours working on a paper in Google Docs on a browswer at a public terminal. And here's problem #1: there's no footnotes function in Google Docs! My MS Word footnotes do still appear in the document, but at the end. Instead of footnotes, Google Docs has a "comment" function, where you can insert the equivalent of a footnote. I tried using that to insert a few footnotes that needed inserting.

Upon returning home, I re-converted the files to MS Word, and noticed the second problem: the Google Docs Comments don't translate back to MS Word comments. Moreover, all the footnotes formatting in the original document is now gone. The footnotes are still in the text, but they aren't actually "coded" as footnotes anymore -- they're just text with a number attached.

Needless to say, if you have upwards of 30 footnotes in your article, this can be a huge pain. Until Google improves both its internal functionality and its compatibility with MS Word, I won't be using Google Docs for any serious writing.

Have other readers worked with Google Docs? Likes, dislikes?

Shockingly, I've noticed that not blogging is sometimes correlated to getting more writing done. Amongst friends and colleagues, I've often argued that this actually isn't the case, that blogging and writing/publishing can in fact be fully complementary. At least for right now, for me, less blogging seems to mean more scholarly productivity. (I might yet change my mind, especially with the onset of Spring Break next week).

* * *

On my non-teaching days I've been doing research at the Van Pelt library at the University of Pennsylvania. I generally don't carry my laptop (it's both heavy and fragile), and for the most part that's not an issue, since most of one's time at the library is spent finding books and articles, photocopying them, and reading them. However, if you actually want to write at a computer, you have to use their public terminals. Some university library terminals have MS Word, but many times you just get a bare-bones Web browser.

But if you have Google, who needs MS Word anyways, right? Haven't we entered the golden age of "all you need is a browser"? (Wrong. And, No.)

For my session this past Monday, I uploaded my Word Docs to Google Docs to get around the public terminal problem. I then spent a couple of hours working on a paper in Google Docs on a browswer at a public terminal. And here's problem #1: there's no footnotes function in Google Docs! My MS Word footnotes do still appear in the document, but at the end. Instead of footnotes, Google Docs has a "comment" function, where you can insert the equivalent of a footnote. I tried using that to insert a few footnotes that needed inserting.

Upon returning home, I re-converted the files to MS Word, and noticed the second problem: the Google Docs Comments don't translate back to MS Word comments. Moreover, all the footnotes formatting in the original document is now gone. The footnotes are still in the text, but they aren't actually "coded" as footnotes anymore -- they're just text with a number attached.

Needless to say, if you have upwards of 30 footnotes in your article, this can be a huge pain. Until Google improves both its internal functionality and its compatibility with MS Word, I won't be using Google Docs for any serious writing.

Have other readers worked with Google Docs? Likes, dislikes?

I'll take the bronze

Congratulations to Falstaff on winning "Best Humanities Blog" at the IndiBloggies, with 141 votes. Falstaff actually lives in the Philadelphia area, so it's slightly odd that we've never met. (Well, not that odd, considering that I spend most of my free time these days at Babies R Us, tussling with other "soccer dads" over who gets the last can of powdered Enfamil...) The incredibly prolific Chandrahas also got more votes than me (110). See his brilliant and scholarly comparison of William Blake to an Oriya devotional poet named Salebaga here.

To the 91 people who voted for me, thanks for your support! I appreciate you taking the time to navigate the Indibloggies' rather convoluted voting system.

I also wanted to congratulate Greatbong, for winning blog of the year. He is actually quite funny, and has a way with words -- both Hindi and English (though, perhaps, surprisingly, not Bangla). I'm not quite sure I'd be as quick to joke about the Samjhauta bombing as he is, but you can't go wrong finding silly stuff to laugh about and/or cringe over in big Bollywood multi-starrers.

To the 91 people who voted for me, thanks for your support! I appreciate you taking the time to navigate the Indibloggies' rather convoluted voting system.

I also wanted to congratulate Greatbong, for winning blog of the year. He is actually quite funny, and has a way with words -- both Hindi and English (though, perhaps, surprisingly, not Bangla). I'm not quite sure I'd be as quick to joke about the Samjhauta bombing as he is, but you can't go wrong finding silly stuff to laugh about and/or cringe over in big Bollywood multi-starrers.

"Samjhauta" Thwarted: Another Senseless, Horrible Bombing

It's difficult to know what to say sometimes after terrorist attacks like the recent bombing of the Samjhauta Express. 68 innocent people lost their lives -- and for what? If it turns out to be an attack planned by Kashmiri militants or other Islamists, this kind of attack seems particularly bizarre, as it appears that the majority of the people who died were in fact Pakistanis. (If another motive or ideological agenda was behind the attack, it's not as if it would be any better.) And needless to say, if this follows the pattern of some other recent terrorist attacks in India, it's entirely possible -- likely, even -- that weeks will go by without any satisfactory answers appearing. (I'm perfectly happy to be proven wrong if this turns out not to be true.)

Here are some of the issues I've seen people discussing with regards to this attack:

Here are some of the issues I've seen people discussing with regards to this attack:

- At Outlook, there is an interesting article that describes in depth the general lack of security on the Samjhauta Express train. Hopefully, both governments are going to seriously revamp this.

- A big question that people are asking is, were the doors locked from the inside, preventing people who survived the original explosions from escaping the two burning cars? Some witnesses have claimed they were, but India has denied it. At Bharat-Rakshak, however, I came across a commenter who has a good explanation for why this might have been done:

In north India, when travelling overight, train compartments are usually locked from inside to prevent entry of people who do not have reservations in that compartment. The TT opens them at stations to allow entry only the passengers that belong to that compartment.

With intense heat, the locked door latches must have jammed. It is difficult to open these latches even otherwise. Women and kids have to ask other passengers to help then open the door.

The windows in trains are barred to prevent 'chain snatching' and other types of burglaries. (link)

Those sound like good reasons, but I hope after this tragedy officials are thinking about possible failsafe mechanisms, so nothing like this happens again. - Sketches have been released of the suspects. They were apparently speaking the "local Hindi language." That doesn't tell us much, however.

- What was the explosive used? The bombs are being described as IEDs with kerosene and other "low intensity" fuels -- in other words, not RDX or other material obtained through transnational networks. These sound like materials that are very easily available, but still incredibly deadly for people in a confined space. A witness at the BBC mentions that the explosions did not force the conductor to stop the train right away -- indeed, he may not have known about them until several minutes after the fires started.

Vote For Me, If You LIke: IndiBloggies

I've been nominated for "Best Humanities Blog," in the 2006 IndiBloggies. You can vote for me here [UPDATE: Voting has now closed]. Voting continues through February 20th.

Though recently most of my blogging has been short-form, I think I did some decent posts in 2006, and many of the more substantial entries are listed on the sidebar. But since I haven't actually updated the sidebar in several months, here are some of the highlights from between October and December:

Masud Khan

2006 in South Asia-oriented books

Anthems of Resistance: Progressive Urdu Poetry

The Myth of Martial Races

Nabokov, Butterflies, Mimesis

The Silencing of Tenzin Tsundue

Macacas, Youtube, and the Question of Respect

The Illusionist vs. The Prestige

Notes on MLA and SALA

Gandhi-Giri in Full Bloom

Though recently most of my blogging has been short-form, I think I did some decent posts in 2006, and many of the more substantial entries are listed on the sidebar. But since I haven't actually updated the sidebar in several months, here are some of the highlights from between October and December:

Masud Khan

2006 in South Asia-oriented books

Anthems of Resistance: Progressive Urdu Poetry

The Myth of Martial Races

Nabokov, Butterflies, Mimesis

The Silencing of Tenzin Tsundue

Macacas, Youtube, and the Question of Respect

The Illusionist vs. The Prestige

Notes on MLA and SALA

Gandhi-Giri in Full Bloom

MTV Desi, RIP

Back in 2005, I mentioned, with some excitement, the advent of MTV Desi, a channel geared to NRIs and Second Generation South Asian American youth. Now there are news reports that MTV Desi is getting axed, along with its sister diasporic channels MTV Chi and MTV K, as Viacom is undergoing a restructuring. Hollywood Reporter has an MTV executive making the following statement:

Well, duh, if it's only available on premium channels on from one Satellite TV company (DirecTV), you can bet people aren't about to go out of their way to get it. I'm actually the only person I know who subscribes to the channel -- and it's only because my in-laws came to stay with us for a few months, and the channel came packaged with the channels they really wanted -- Star One, Star Plus, Star News, and NDTV. Still, I've actually spent some hours watching the channel, so it might be worth doing a mini-elegy.

First, the positive. The best thing I ever saw on MTV Desi was the following inspired rant by Parag Khanna.

There are some statements he makes that miss the mark (India isn't the poorest country in the world by the indices I've seen), but I appreciate the energy. Instead of being the embarrassed, cautious ABCD -- do we really know enough about India to comment on corruption? shouldn't we stay "positive"? -- he's taking a strong stance. (Parag Khanna might make a good blogger.) If MTV Desi is really dead, it's too bad we'll get less stuff like this.

But it should also be admitted that the channel currently plays far too much repetitious programming. The repetition factor can be especially bad when the old programs are tied in with a particular holiday -- as of last week, you would still see the occasional VJ wishing you a "Happy Diwali!" That's pretty lame, considering it's February.

Second, while I love having a TV channel that plays both cool Bollywood and Bhangra tracks and bands like Jahcoozi and M.I.A., far too many videos on the regular playlist are crass booty-shaking exploitation. I have a kid at home now, and while he's too young to understand why there are all these scantily clad blond women shaking their hips while a brown guy lip syncs about his adoration of "Paisa," it's still faintly embarrassing. In an ideal world, I would take the Kailash Khers and the sweet A.R. Rahman songs, and leave the Bollytrash out.

Third, MTV Desi has some pretty lame skits. The "F*#@ing with Eames" skit never made much sense to me -- why is it Desi? Who cares? The parody "Deep Throat" commercial was funnier, and it's too bad Viacom has had it pulled from Youtube.

Most of the music videos one finds on MTV Desi can readily be found on Youtube. And they aren't likely to be pulled for copyright reasons, since most of them derive either from Indie bands like the brilliant King Khan and BBQ Show, who actually want the potential for free publicity online, or Indian music companies, who simply haven't been putting very much effort into that sort of thing.

So really, at the current moment there isn't truly a need for a channel like MTV Desi, especially if you have to pay for something a dedicated blogger/video podcaster could do in her basement for free. Most of the music content could be aggregated, and original content (like the Parag Khanna rant above) could be generated by enterprising college students with video cameras, again for free.

"Unfortunately, the premium distribution model for MTV World proved more challenging than we anticipated in this competitive environment," the company said. "As a result, MTV has decided to shut down its linear MTV World operation. However, we remain steadfast in superserving multicultural youth, and we are continuing to investigate ways to integrate the MTV Desi, Chi and K brands online and on our other screens." (link)

Well, duh, if it's only available on premium channels on from one Satellite TV company (DirecTV), you can bet people aren't about to go out of their way to get it. I'm actually the only person I know who subscribes to the channel -- and it's only because my in-laws came to stay with us for a few months, and the channel came packaged with the channels they really wanted -- Star One, Star Plus, Star News, and NDTV. Still, I've actually spent some hours watching the channel, so it might be worth doing a mini-elegy.

First, the positive. The best thing I ever saw on MTV Desi was the following inspired rant by Parag Khanna.

There are some statements he makes that miss the mark (India isn't the poorest country in the world by the indices I've seen), but I appreciate the energy. Instead of being the embarrassed, cautious ABCD -- do we really know enough about India to comment on corruption? shouldn't we stay "positive"? -- he's taking a strong stance. (Parag Khanna might make a good blogger.) If MTV Desi is really dead, it's too bad we'll get less stuff like this.

But it should also be admitted that the channel currently plays far too much repetitious programming. The repetition factor can be especially bad when the old programs are tied in with a particular holiday -- as of last week, you would still see the occasional VJ wishing you a "Happy Diwali!" That's pretty lame, considering it's February.

Second, while I love having a TV channel that plays both cool Bollywood and Bhangra tracks and bands like Jahcoozi and M.I.A., far too many videos on the regular playlist are crass booty-shaking exploitation. I have a kid at home now, and while he's too young to understand why there are all these scantily clad blond women shaking their hips while a brown guy lip syncs about his adoration of "Paisa," it's still faintly embarrassing. In an ideal world, I would take the Kailash Khers and the sweet A.R. Rahman songs, and leave the Bollytrash out.

Third, MTV Desi has some pretty lame skits. The "F*#@ing with Eames" skit never made much sense to me -- why is it Desi? Who cares? The parody "Deep Throat" commercial was funnier, and it's too bad Viacom has had it pulled from Youtube.

Most of the music videos one finds on MTV Desi can readily be found on Youtube. And they aren't likely to be pulled for copyright reasons, since most of them derive either from Indie bands like the brilliant King Khan and BBQ Show, who actually want the potential for free publicity online, or Indian music companies, who simply haven't been putting very much effort into that sort of thing.

So really, at the current moment there isn't truly a need for a channel like MTV Desi, especially if you have to pay for something a dedicated blogger/video podcaster could do in her basement for free. Most of the music content could be aggregated, and original content (like the Parag Khanna rant above) could be generated by enterprising college students with video cameras, again for free.

Peter Nicholson on Auden, and against the "Poetic"

The Auden centenary is coming up, and Peter Nicholson has posted his poem, "Asking Auden," from 1984 at 3 Quarks Daily (seems we're in a linking-to-3QD mood over here). He's also posted a short essay with some reflections on the function of criticism, specifically poetry criticism. The highlight for me is the following:

(I had to look up "falls the shadow, Cynara". Did you?)

I like Nicholson's general point here. While good criticism can be helpful and insightful, it's almost never really "authoritative," partly because even benchmark critics have their own spots of extreme idiosyncrasy, and partly because every reader brings an essentially unique combination of taste, experience, and intelligence to the text at hand.

There is a problem specific to poetry: mistaken thinking about poetry by the general public. Misuse of the word 'poetic' is so common as to be beyond repair. Proper poetry dives into the world, takes in its multifariousness, its roughnesses and tragedies, its joy at beauty, even as the poet grabs on to the broken glass shards of the Muse's patchy visitations. 'Poetic' is not another word for nice, kind, sedate, palatable. Between top-heavy pronouncements from various spots around the publishing globe and the general public's indifference to the real poetic, falls the shadow, Cynara, of the individual writer's efforts to get him or herself understood on a proper footing.

It's true, as Robert Hughes said in Australia recently—a critic has to have a harsh side, otherwise all you get is blandout. That apart, critics will come in many guises. One will behave like Stalin, casting the unchosen to outer darkness. Another will gather in a sheaf of sensibilities with an almost creative zeal. A few imply they have read everything and therefore their commentaries come with an air of supernal wisdom. Nothing of the kind, of course. . . . Personally, I can't think of any critics with whom I am in general agreement about literature or art. When reading all these people you can get an interesting perspective, learn new things about art and artists, enjoy the erudition, if worn lightly. However, in art, it is essential not to let others do the thinking for you. Perhaps that's even more important with artists you admire and who write on art too. I often disagree with some of my favourite artists. Wagner seems misguided on all manner of subjects. 'Poetry makes nothing happen' and 'All art is quite useless' are two statements from Auden and Wilde that irritate me.(link)

(I had to look up "falls the shadow, Cynara". Did you?)

I like Nicholson's general point here. While good criticism can be helpful and insightful, it's almost never really "authoritative," partly because even benchmark critics have their own spots of extreme idiosyncrasy, and partly because every reader brings an essentially unique combination of taste, experience, and intelligence to the text at hand.

Alternadad, Parenting in Literary History

I don't have that much in common with Neal Pollack, except maybe a certain attitude, but I still read about his book Alternadad with great interest. Here's Michael Agger's reading of it in Slate:

As I said, I don't have that much in common with Pollack (the religion question is a non-issue, for instance), though many of the questions raised in this review of his book in Slate are ones I'm thinking about too: as in, how to rethink conventional gender roles to support slightly non-traditional (in my case) careers. Also of great interest is how to inject a spirit of originality -- one's own idiosyncratic taste -- into parenting in a way that's both "cool" and nurturing.

As a side note, maybe I should follow Pollack's lead, and write an article (or book?) related to parenting sometime: parents and parenting in literary history. James Joyce was an unusual dad, though not a very good one, I gather. Rabindranath Tagore was in many ways a better father -- still highly unconventional -- though there are questions about him marrying off his daughter in a child marriage.

Of course those are only biographical bits -- the "real" question might be, how and whether writers posed characters as parents in their fiction. In some cases, it didn't matter whether they were parents or not: Virginia Woolf, for instance, did not have children, but she created some very memorable mothers in her novels -- Mrs. Dalloway and Mrs. Ramsay.

Other famous parents in fiction?

What's fallen away from marriage for artist-intellectual-professional types are the traditional genders and gender roles. But, as new moms have been observing for years, the arrival of a child has a nasty way of reinstating the old dynamic. Pollack, who feels the need to make money and provide a safe place to live, is among the first to relate the re-emergence of breadwinner angst among men. (Although he fights this pressure by smoking pot and forming a rock band.) Regina is divided by wanting space for her artistic ambitions and her feelings of being a "bad mother." Parenthood, which looks from the outside like a step into maturity, is actually a descent into a new set of insecurities. Including renewed tension with your parents, who are often willing to overlook a funky wedding ceremony but want to see you step in with tradition and/or religion when a grandchild appears. An infamous chapter in Alternadad details the three-way gunfight among Neal, Regina, and Neal's Jewish parents over whether Eli should be circumcised.

As I said, I don't have that much in common with Pollack (the religion question is a non-issue, for instance), though many of the questions raised in this review of his book in Slate are ones I'm thinking about too: as in, how to rethink conventional gender roles to support slightly non-traditional (in my case) careers. Also of great interest is how to inject a spirit of originality -- one's own idiosyncratic taste -- into parenting in a way that's both "cool" and nurturing.

As a side note, maybe I should follow Pollack's lead, and write an article (or book?) related to parenting sometime: parents and parenting in literary history. James Joyce was an unusual dad, though not a very good one, I gather. Rabindranath Tagore was in many ways a better father -- still highly unconventional -- though there are questions about him marrying off his daughter in a child marriage.

Of course those are only biographical bits -- the "real" question might be, how and whether writers posed characters as parents in their fiction. In some cases, it didn't matter whether they were parents or not: Virginia Woolf, for instance, did not have children, but she created some very memorable mothers in her novels -- Mrs. Dalloway and Mrs. Ramsay.

Other famous parents in fiction?

Begum Nawazish Ali Running For Parliament in Pakistan

So, there was a big article in the New York Times recently (thanks, TechnophobicGeek) about how Indian TV is supposedly entering this golden age of innovative programming. Some of the shows mentioned have actually been talked about before at Sepia Mutiny, including "Galli Galli Sim Sim." There's also an interesting segment on a new reality show oriented to teenagers, called "Dhoom Machao Dhoom," about four girls who want to start a band. One of them is a "returned" ABCD from New York, which makes for interesting drama when she says they should write their own songs instead of just doing Bollywood numbers (the other girls refuse, saying "Only Bollywood works here").

Anyway, it's a decent read, but it strikes me that Indian TV remains a narrow-minded backwater as long as Pakistan has Begum Nawazish Ali. Via 3 Quarks Daily, I came across a new profile at MSNBC of Pakistan's famous celebrity drag queen and talk show host. Among other things, the Begum freely admits her "bisexuality," though I'm not sure she means it the way we might think she means it. (Venial Sin, as you may remember, wasn't thrilled about her performance: "I mean, kudos to Begum Nawazish Ali for getting to pull a tranny routine on TV, but how necessary is it to reiterate the stereotypes of a gay man as an effeminate 'woman stuck in a male body' or as a hijra?")

But now comes the news that she plans to run for Pakistani Parliament:

Interesting -- we'll see if her political career (is she really serious?) is going to be as groundbreaking as her showbiz career has been.

There are many theories about how it is the Begum can get away with it in conservative Pakistan. She's been careful not to be crude in the Dame Edma vein, but still -- there are some serious social taboos being transgressed here. What do you think?

In case you're wondering what the fuss is about, I might recommend this 10 minute Youtube clip of the Begum doing her thing. The jokes are corny, but the sari and make-up are exquisite.

Anyway, it's a decent read, but it strikes me that Indian TV remains a narrow-minded backwater as long as Pakistan has Begum Nawazish Ali. Via 3 Quarks Daily, I came across a new profile at MSNBC of Pakistan's famous celebrity drag queen and talk show host. Among other things, the Begum freely admits her "bisexuality," though I'm not sure she means it the way we might think she means it. (Venial Sin, as you may remember, wasn't thrilled about her performance: "I mean, kudos to Begum Nawazish Ali for getting to pull a tranny routine on TV, but how necessary is it to reiterate the stereotypes of a gay man as an effeminate 'woman stuck in a male body' or as a hijra?")

But now comes the news that she plans to run for Pakistani Parliament:

Then Saleem dropped a bombshell. "You are the first person I am announcing this to, but I have decided to file my papers for the upcoming general elections," he exclaimed. "I am going to run for a parliamentary seat as an independent from all over Pakistan and I am going to campaign as Begum Nawazish Ali!" The note of triumph and excitement in his voice is unmistakable.

"I want to be the voice of the youth and for all of Pakistan," he continued. "The idea was always to break barriers and preconceived notions, of gender, identity, celebrity and politics and to bring people closer. In any case, I think Begum Nawazish Ali is the strongest woman in Pakistan!"

Whether Pakistanis agree or not, the elections at the end of the year are likely to be one of the most uproarious in recent times. (link)

Interesting -- we'll see if her political career (is she really serious?) is going to be as groundbreaking as her showbiz career has been.

There are many theories about how it is the Begum can get away with it in conservative Pakistan. She's been careful not to be crude in the Dame Edma vein, but still -- there are some serious social taboos being transgressed here. What do you think?

In case you're wondering what the fuss is about, I might recommend this 10 minute Youtube clip of the Begum doing her thing. The jokes are corny, but the sari and make-up are exquisite.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)