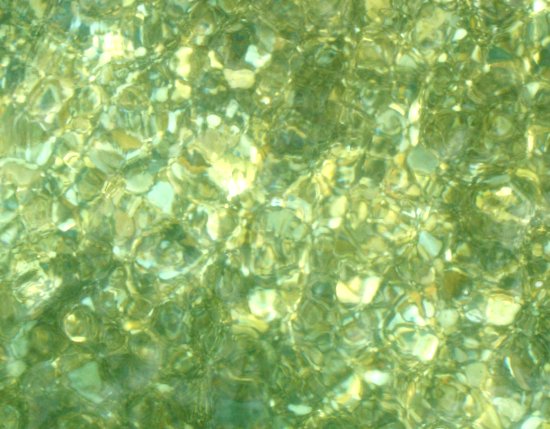

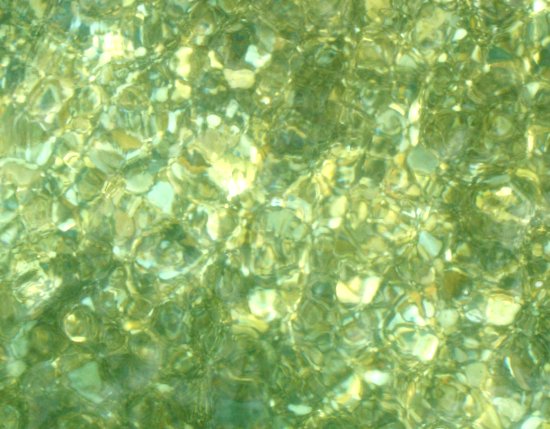

I swear, I haven't done any Photoshop wackiness to this picture, just improved contrast. That's how the rocks looked through the water (I was standing on a pier).

People fishing at Cedar Beach, Long Island.

Postcolonial/Global literature and film, Modernism, African American literature, and the Digital Humanities.

The report says that Bollywood has bigger draw on customers than any other medium. Each film is a brand in itself and with every new movie there is a fresh new brand of fashion and lifestyle products.

But film critic A C Tuli says "only those designs which can be worn daily by the masses become a fashion statement. Rest do not."

Tuli says in last decade or so, most of the new heroines are shown wearing skinny tops, skirts, gowns etc. They fail to become popular as they cannot be worn daily and by the middle class."

Agrees Ritu Sethi, a boutique owner, "we are getting lot of orders for Parineeta's blouses and Babli's fitted pathani shirts with contrast collars and cuffs." Also in demand are colourful kurtis teamed with baggy, equally colourful pyjamas and cloth bags for women and fitted sleveless shirts and denims.

"Bunty and Babli has defined hip street style this season," says Sethi.

The trend of Bollywood inspiring fashion is not new, Saystuli. In the early 50s, clothing materials were named after Suraiya and Madhubala.

Nargis, the lady in white brought to fore, white sarees -both embroidered and bordered. Raj Kapoor's trousers with folded up holes and scarf in the neck remained popular for a long time. In fact, those who did not adopt this trend were called backward.

"Dev Anand popularised full sleeves top collared shirts and puffy hair, Sadhna's fringe, leg-hugging pyjamis and no side split kurtis were a rage with college girls in 60s, even though they were very uncomfortable to wear," he says.

In 70s, as the heroes shifted from trousers to bellbottoms, so did the young crowd in cities. Rajesh Khanna's guru shirts (collarless) were popular with young men. However, he says most of these fashions last only a season or till another new hit comes.

I had no idea where I was going

How I lived or what I did here

the yawning gulf between

Hangs like a rope from a wooden beam

Breathing life into these stone-cold lips

Putting gas in this battered old stretch limousine

City of London

Above this unquiet grave

I smell the smell of decay

And stumble through the streets of grey

It never rains but it sometimes does

Please, sir, can I have some more?

How long can you carry on?

Till the empire's built and die empire's gone

City of London (full lyrics here)

I see the cities of the earth, and make myself a

part of them,

I am a real Londoner, Parisian, Viennese,

I am a habitan of St. Petersburgh, Berlin, Constantinople,

I am of Adelaide, Sidney, Melbourne,

I am of Manchester, Bristol, Edinburgh, Limerick,

I am of Madrid, Cadiz, Barcelona, Oporto, Lyons,

Brussels, Berne, Frankfort, Stuttgart, Turin,

Florence,

I belong in Moscow, Cracow, Warsaw -- or north-

ward in Christiana or Stockholm -- or in

some street in Iceland,

I descend upon all those cities, and rise from them

again.

Life, friends, is boring. We must not say so.

After all, the sky flashes, the great sea yearns,

we ourselves flash and yearn,

and moreover my mother told me as a boy

(repeatedly) ‘Ever to confess you’re bored

means you have no

Inner Resources.’ I conclude now I have no

inner resources, because I am heavy bored.

Peoples bore me,

literature bores me, especially great literature,

Henry bores me, with his plights & gripes

as bad as achilles,

who loves people and valiant art, which bores me.

And the tranquil hills, & gin, look like a drag

and somehow a dog

has taken itself & its tail considerably away

into mountains or sea or sky, leaving

behind: me, wag.

No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man's and yet as mortal as his own; that as men busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinised and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinise the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacency men went to and fro over this globe about their little affairs, serene in their assurance of their empire over matter. It is possible that the infusoria under the microscope do the same. No one gave a thought to the older worlds of space as sources of human danger, or thought of them only to dismiss the idea of life upon them as impossible or improbable. It is curious to recall some of the mental habits of those departed days. At most terrestrial men fancied there might be other men upon Mars, perhaps inferior to themselves and ready to welcome a missionary enterprise. Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us. And early in the twentieth century came the great disillusionment.

For so it had come about, as indeed I and many men might have foreseen had not terror and disaster blinded our minds. These germs of disease have taken toll of humanity since the beginning of things--taken toll of our prehuman ancestors since life began here. But by virtue of this natural selection of our kind we have developed resisting power; to no germs do we succumb without a struggle, and to many--those that cause putrefaction in dead matter, for instance--our living frames are altogether immune. But there are no bacteria in Mars, and directly these invaders arrived, directly they drank and fed, our microscopic allies began to work their overthrow. Already when I watched them they were irrevocably doomed, dying and rotting even as they went to and fro. It was inevitable. By the toll of a billion deaths man has bought his birthright of the earth, and it is his against all comers; it would still be his were the Martians ten times as mighty as they are. For neither do men live nor die in vain.

Of 1826

I am the little man who smokes & smokes.

I am the girl who does know better but.

I am the king of the pool.

I am so wise I had my mouth sewn shut.

I am a government official & a goddamned fool.

I am a lady who takes jokes.

I am the enemy of the mind.

I am the auto salesman and love you.

I am a teenager cancer, with a plan.

I am the blackt-out man.

I am the woman powerful as a zoo.

I am two eyes screwed to my set, whose blind--

It is the Fourth of July.

Collect: while the dying man,

forgone by you creator, who forgives,

is gasping 'Thomas Jefferson still lives'

in vain, in vain, in vain.

I am Henry Pussy-cat! My whiskers fly.

It was the first blogged war, and the characteristic features of the form--instant response, ad-hominem attack, remoteness from life, the echo chamber of friends and enemies--helped define the tone of the debate about Iraq. One of the leading bloggers, Andrew Sullivan, responded to the news of Saddam's capture, in December 2003, by writing, 'It was a day of joy. Nothing remains to be said right now. Joy.' He had just handed out eleven mock awards to leftists who expressed insufficient happiness or open unhappiness at the news. . . . Sullivan's joy was, in fact vindictive and narcissistic glee. (He has since had second thoughts about the Administration's conduct of the war.) Similarly, as the insurgency sent Iraq into tumult most antiwar pundits and politicians, in spite of the enormous stakes and the awful alternatives, showed no interest in helping Iraq become a stable democracy. When Iraqis risked their lives to vote, Arianna Huffington dismissed the elections as a 'Kodak moment.' It was Bush's war, and, if it failed, it would be Bush's failure.

April 11, 2004

I don't believe in writer's bloc--I'm not working up to a big analysis of why one can go for so long without writing. I don't go in for that whole think of like (Spinal Tap accent in place) 'Look man . . . it's impossible to [insert any for mof creative work] write now. I can't do it, and I don't know when . . . [dramatic pause] or if . . . I'll be able to do it again, man.' I mean it ain't backbreaking work, writing. And there's no sense in making a precious and larger-than-life practice of it. I think that things like music, writing, filmmaking are all blue-collar jobs, and I think that it just gets worse and worse the more people try to position themselves or their craft as anything more lofty than what basically amounts to a job in the service of others. One of my all-time favorite quotes about the creative process of writing comes from Neal Pollack: 'I don't see writing as some sort of holy act. When the phone rings, I answer it.' Having said all of that, it has taken me a month to sit back down in front of this page. Maybe you can't control when inspiration will strike, but there is something to be said for the discipline of showing up so that when it comes around you'll be there waiting.