"Just remember that your real job is that if you are free, you need to free somebody else. If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else." --Toni Morrison

The SAJA South Asian Writers Panel According to...

Elck, @ Vernacular Body. An excellent, thorough account of the event; it makes me sorry I missed it.

India adopts New Patents on AIDS drugs

My first thought is: oh, crap. This just to get WTO membership?

But if you read further into it, it begins to seem a little more complicated. For one thing, the already-approved generics can still be produced. There will be a new licensing fee, but it isn't specified how much that will come out to. So it's possible the price rise for India's generic AIDS drugs will be incremental rather than exponential; we'll have to wait and see.

But if you read further into it, it begins to seem a little more complicated. For one thing, the already-approved generics can still be produced. There will be a new licensing fee, but it isn't specified how much that will come out to. So it's possible the price rise for India's generic AIDS drugs will be incremental rather than exponential; we'll have to wait and see.

A waste of an evening... almost

Because of the snow, my one-hour commute took three hours tonight. Ouch.

Well, anyway, I made good use of my IRiver MP3 (recent acquisition) player. I have a little device which I found on line, that broadcasts your MP3 player's output to a radio station you set. Pretty nifty; it lets you listen in the car. (Headphones and driving don't mix, in my opinion)

During the endless traffic jam, I listened to the podcasts of KCRW interviews with Malcolm Gladwell (Blink), Marilynne Robinson (Gilead), and about half of Lawrence Lessig's Free Culture from the 'open source' free audiobook compiled by a bunch of bloggers.

The highlight was probably the Lessig, which is very well-written. Lessig's argument, also, is truly a far cry from the simplistic 'Free Napster' type of argument that I'd kind of expected. People who are thinking about Intellectual Property issues online really ought to check it out...

Well, anyway, I made good use of my IRiver MP3 (recent acquisition) player. I have a little device which I found on line, that broadcasts your MP3 player's output to a radio station you set. Pretty nifty; it lets you listen in the car. (Headphones and driving don't mix, in my opinion)

During the endless traffic jam, I listened to the podcasts of KCRW interviews with Malcolm Gladwell (Blink), Marilynne Robinson (Gilead), and about half of Lawrence Lessig's Free Culture from the 'open source' free audiobook compiled by a bunch of bloggers.

The highlight was probably the Lessig, which is very well-written. Lessig's argument, also, is truly a far cry from the simplistic 'Free Napster' type of argument that I'd kind of expected. People who are thinking about Intellectual Property issues online really ought to check it out...

Paul Berman, on the "Unworldliness" of the American Left

Via Literary Saloon, I came across a Paul Berman essay in the new Bookforum. It's Berman considering the career of the sociologist Daniel Bell, who published a series of books analyzing the American left, starting in the late 19th century.

The highlight for me are the following paragraphs, summarizing the argument of Bell's book Marxian Socialism in the United States:

Being a person who likes to think of himself as both in the world, and of it -- and being no big fan of Ralph Nader -- I want to agree with Berman on this characterization. Using the polemical charge of Bell's religious metaphor, Berman turns Marxist idealism into a kind of Priesthood.

But I know several left-leaning folks (Michael Hardt, for instance) who don't fit this characterization at all. There are more complex ways of using and working with idealism than Berman allows. That one rejects certain dominant political and economic frameworks on ethical grounds doesn't necessarily mean one harbors unrealistic ideas about human nature (one thinks of the old cliché that Marxists believe humanity must suddenly turn altruistic for the systme to work). In my view, it's quite possible for realism and idealism not to contradict each other. But it requires a somewhat more multi-dimensional way of thinking about political ideology than the tired old Left-Right axis.

Berman also continues to work with the Marxism-as-religion metaphor beyond where it is probably useful. The following paragraph, for instance, doesn't make very much sense to me:

A textbook case of mixed metaphors, this. Reading the above paragraph reminds me why it's wrong to do it: the problem isn't that mixed metaphors will annoy Grammar Sticklers, but rather that no one will know what you're talking about.

Still, an interesting read overall from Paul Berman, author of the interesting (if a little maddening) Terror and Liberalism, a book much-talked about in the blog-world a couple of years ago.

The highlight for me are the following paragraphs, summarizing the argument of Bell's book Marxian Socialism in the United States:

Marxian Socialism in the United States is a work of great psychological acuity. Martin Luther said of the church that it was "in the world, but not of it," and Bell quoted this remark to evoke a quality of unworldliness in the American Left. He meant that, over the decades, the socialist movement in America had never quite been able to accept the political world as it was, preferring instead to dwell apart, in a world of dreams and moral postures. Marxian Socialism in the United States has received, over the years, mountains of criticism for this one quotation from Luther. And yet something about that phrase has always been on the mark, as I think anyone can see, with a glance at Debs's four presidential campaigns at the start of the twentieth century, and at Ralph Nader's two campaigns at the start of the twenty-first.

The phrase "in the world, but not of it" strikes me as pretty astute on the topic of the New Left, too—the New Left that commanded the allegiance of several million Americans in the '60s and '70s but was never able to break into conventional political life, with a couple of exceptions. For the New Left too preferred to dwell apart, in its own world of dreams and moral postures. This habit did the movement no harm at all, by the way, in regard to cultural issues—which is why it succeeded in capturing whole neighborhoods in a number of cities, and used those neighborhoods to conduct experiments on cultural matters, and sent those experiments orbiting outward to the rest of American society. Nor did a few unworldly habits do the New Left any harm at the universities, once the graduate-student militants had succeeded in shoving aside the populist anti-intellectuals. But the kind of movement that was capable of capturing a student neighborhood or an English department was never going to capture a state assembly.

Being a person who likes to think of himself as both in the world, and of it -- and being no big fan of Ralph Nader -- I want to agree with Berman on this characterization. Using the polemical charge of Bell's religious metaphor, Berman turns Marxist idealism into a kind of Priesthood.

But I know several left-leaning folks (Michael Hardt, for instance) who don't fit this characterization at all. There are more complex ways of using and working with idealism than Berman allows. That one rejects certain dominant political and economic frameworks on ethical grounds doesn't necessarily mean one harbors unrealistic ideas about human nature (one thinks of the old cliché that Marxists believe humanity must suddenly turn altruistic for the systme to work). In my view, it's quite possible for realism and idealism not to contradict each other. But it requires a somewhat more multi-dimensional way of thinking about political ideology than the tired old Left-Right axis.

Berman also continues to work with the Marxism-as-religion metaphor beyond where it is probably useful. The following paragraph, for instance, doesn't make very much sense to me:

"Among the radical, as among the religious minded," [Daniel Bell] wrote, "there are the once born and the twice born. The former is the enthusiast, the ‘sky-blue healthy-minded moralist' to whom sin and evil—the ‘soul's mumps and measles and whooping coughs,' in Emerson's phrase—are merely transient episodes to be glanced at and ignored in the cheerful saunter of life. To the twice born, the world is ‘a double-storied mystery' which shrouds the evil and renders false the good; and in order to find truth, one must lift the veil and look Medusa in the face."

A textbook case of mixed metaphors, this. Reading the above paragraph reminds me why it's wrong to do it: the problem isn't that mixed metaphors will annoy Grammar Sticklers, but rather that no one will know what you're talking about.

Still, an interesting read overall from Paul Berman, author of the interesting (if a little maddening) Terror and Liberalism, a book much-talked about in the blog-world a couple of years ago.

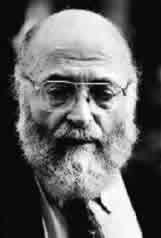

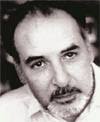

Writers with Beards @ Book Coolie

Book Coolie is starting a series of posts appreciating Writers with beards [DEAD LINK]. First up is Anton Chekhov. Go read it...

I really like this project, and I might also ask: which writers have beards, and which don't? At the risk of stealing Coolie's thunder, let me also nominate the following gentlemen for consideration:

[Incidentally, if you click on the images, you will find the original context.]

Charles Dickens

Hemingway

D.H. Lawrence

Lytton Strachey

Thomas Carlyle

William Morris

Dostoevsky

Wole Soyinka

J.M. Coetzee

Chaim Potok

Alain Robbe-Grillet

Tahar Ben Jalloun

Rohinton Mistry

Pankaj Mishra

Is there a pattern? One can compare the bearded to the non-bearded male writers.

And as of this moment, I haven't been able to identify a pattern -- the result of the experiment (conducted with the help of images.google.com) is negative. But it's not entirely hopeless; I solicit your help.

Here's some data from my lunch-hour experiment:

Charles Dickens had a beard, but William Makepeace Thackeray and Henry James did not. D.H. Lawrence had a beard, but Joyce, Proust, and T.S. Eliot did not. I have trouble finding French writers with beards -- even Honore de Balzac, who seems like he almost requires a beard -- didn't have one (though he did have a bushy mustache). But then, Robbe-Grillet has a beard, so throw that out.

Very few Arab writers have beards (one can certainly speculate as to why; clean-shaven suggests "secular"). But the very secular Tahar Ben Jalloun has a beard, though it is closely cropped -- you wouldn't confuse it with the beards worn by devout Muslim men.

I can't find any Latin American writers with beards. And most of the Jewish and Israeli writers I can think of offhand (the two Roths, Amos Oz, A.B. Yehoshua) don't have beards, though Chaim Potok does. (But then Potok is a former Hasid, so it kind of makes sense.)

I thought maybe gay men would tend to be less likely to have beards. And indeed, Marcel Proust, Henry James, Roland Barthes, and Jean Genet don't have beards. But Strachey has quite a beard! So that rule doesn't quite work.

Maybe experimental, avant-gardist writers don't have beards? No beard on Borges, Kafka, or Joyce. But Coetzee has one, so scratch that too.

With the African writers, I think it's somehow fitting that Soyinka has a beard, but Achebe doesn't. I also think Dickens (yes) vs. Thackeray (no) makes sense, in terms of the way they write.

But with the others... ? There does seem to be a correlation between writers who pose themselves as self-consciously "serious" or "philosophical" and beardedness. But it's only a rough correlation, hardly a rule.

Finally, some of you may have noticed that this completely useless exercise obviously only includes writers who are men! I'm curious to know whether women writers could also be categorized with some superficial aspect of their appearance? I don't think so -- beards have a kind of historical constancy to them since the 19th century: they are sort of always a little out of fashion, but suitable for writers and philosophers. Whereas women's dress and hair have changed quite radically during the same era. Perhaps: women writers who keep their hair pulled back vs. those who have their hair down? Short vs. long hair?

I really like this project, and I might also ask: which writers have beards, and which don't? At the risk of stealing Coolie's thunder, let me also nominate the following gentlemen for consideration:

[Incidentally, if you click on the images, you will find the original context.]

Charles Dickens

Hemingway

D.H. Lawrence

Lytton Strachey

Thomas Carlyle

William Morris

Dostoevsky

Wole Soyinka

J.M. Coetzee

Chaim Potok

Alain Robbe-Grillet

Tahar Ben Jalloun

Rohinton Mistry

Pankaj Mishra

Is there a pattern? One can compare the bearded to the non-bearded male writers.

And as of this moment, I haven't been able to identify a pattern -- the result of the experiment (conducted with the help of images.google.com) is negative. But it's not entirely hopeless; I solicit your help.

Here's some data from my lunch-hour experiment:

Charles Dickens had a beard, but William Makepeace Thackeray and Henry James did not. D.H. Lawrence had a beard, but Joyce, Proust, and T.S. Eliot did not. I have trouble finding French writers with beards -- even Honore de Balzac, who seems like he almost requires a beard -- didn't have one (though he did have a bushy mustache). But then, Robbe-Grillet has a beard, so throw that out.

Very few Arab writers have beards (one can certainly speculate as to why; clean-shaven suggests "secular"). But the very secular Tahar Ben Jalloun has a beard, though it is closely cropped -- you wouldn't confuse it with the beards worn by devout Muslim men.

I can't find any Latin American writers with beards. And most of the Jewish and Israeli writers I can think of offhand (the two Roths, Amos Oz, A.B. Yehoshua) don't have beards, though Chaim Potok does. (But then Potok is a former Hasid, so it kind of makes sense.)

I thought maybe gay men would tend to be less likely to have beards. And indeed, Marcel Proust, Henry James, Roland Barthes, and Jean Genet don't have beards. But Strachey has quite a beard! So that rule doesn't quite work.

Maybe experimental, avant-gardist writers don't have beards? No beard on Borges, Kafka, or Joyce. But Coetzee has one, so scratch that too.

With the African writers, I think it's somehow fitting that Soyinka has a beard, but Achebe doesn't. I also think Dickens (yes) vs. Thackeray (no) makes sense, in terms of the way they write.

But with the others... ? There does seem to be a correlation between writers who pose themselves as self-consciously "serious" or "philosophical" and beardedness. But it's only a rough correlation, hardly a rule.

Finally, some of you may have noticed that this completely useless exercise obviously only includes writers who are men! I'm curious to know whether women writers could also be categorized with some superficial aspect of their appearance? I don't think so -- beards have a kind of historical constancy to them since the 19th century: they are sort of always a little out of fashion, but suitable for writers and philosophers. Whereas women's dress and hair have changed quite radically during the same era. Perhaps: women writers who keep their hair pulled back vs. those who have their hair down? Short vs. long hair?

The Chic Sikh: Vikram Chatwal

NOTE: The below image is not of me (Amardeep Singh), it is Vikram Chatwal. I say it because there has often been some confusion about this.

Vikram Chatwal, New York hotel tycoon. Part of an NYT slideshow.

Vikram Chatwal, New York hotel tycoon. Part of an NYT slideshow.

Family matters: Terri Schiavo

Nytimes:

So much for "family values," states' rights, and separation of powers.

While the Senate acted without any objection, the bill ran into resistance from some House Democrats, who said the Republican-led Congress had overstepped its authority by inserting itself into what was a family matter best left to state authorities.

"These actions today are a clear threat to our democracy," said Representative Jim Davis of Florida, one of three Democrats from Ms. Schiavo's home state who joined others in temporarily stalling the bill.

So much for "family values," states' rights, and separation of powers.

Math question: 4 8 15 16 23 42

[UPDATE from October: Some of what is below is obsolete, now that we know that the numbers are the 'reset' code for the mysterious countdown that threatens to "destroy the world," as Desmond put it in last week's episode. We still don't know what the connection might be between these numbers and Hurley's rotten lottery luck, as well as a number of other things relating to the individual characters in the show. And there are all these new mysteries, with the 1960s social research project, the magnetic disturbances on the film clip, and so on. We also don't know exactly what it is that would happen if the clock ever went to "0." Anyway, I think all the math below is still legitimate and interesting.]

This one is for the mathematicians in the house.

Do the following numbers constitute a series?

4 8 15 16 23 42

They are the mystery numbers in the American TV show Lost. The numbers are marked on the hatch of a mysterious, partially buried ship that crashed on the island (pictured above; see Episode 1:18), which also explains the fate of the "French chick" and her crew -- who came to the island after a distress call -- and also Hurley's rotten lottery luck, also linked to a distress call derived from the island. Clearly, the fact that the numbers are marked on the ship suggests they are not supposed to be coordinates. (Someone at one website actually interpreted them as long/lat coordinates, and found they corresponded to a site in south central Africa, which makes no sense given the location of the mystery island.)

The numbers might form some kind of series. On my own, I noticed that if you serialize the difference between the numbers, you get something sort of interesting:

4 8 15 16 23 42

-->4 7 1 7 19

The sum of the difference between numbers 1-4 is the same as the difference between 5-6. Ok, so not that exciting.

I googled the numbers, and the best speculation on how to crack the numbers is at Dodoskido. One of the commentors at that site noticed something a bit more interesting -- that it might be some kind of countdown. The commentor is, like me, using the differentials between each number and repeating the operation. But he's also canceling out the negative between positions 3 (8->15: 7) and 4 (15->15: 1), and beginning the series with 0, as "all mathematicians do."

0 4 8 15 16 23 42

4 4 7 1 7 19

0 3 6 6 12

3 3 0 6

0 3 6

3 3

0

Anyone have ideas about how (0) 4 8 15 16 23 42 might be related in terms of operations other than addition? And: is there software out there that can recognize formulae for series based on strings of numbers? I realize the ways numbers can be patterned are essentially endless, so somehow I doubt it.

My current theory is that the numbers are completely arbitrary -- no series whatsoever. That won't stop people from a) speculating madly, b) selling T-shirts, or even a website called 4815162342.com, though the latter seems like an ABC plant.

Small plug for the desi actor on the show: go Naveen Andrews!

Husband of a Fanatic review in the Times

Amitava Kumar's new book is out in the U.S. (as of a month ago), and there's a review of it in the Times.

The review is a little lukewarm, but balanced on the whole; Bellague describes well what Kumar's style of writing does best. The following paragraph is pretty complimentary:

To which the joker in me adds: How many kar-sevaks does it take to go screw themselves?

But here is one of Bellague's criticisms:

Hm... I for one don't object to "Kumar the professor."

More comments once I've read the book.

The review is a little lukewarm, but balanced on the whole; Bellague describes well what Kumar's style of writing does best. The following paragraph is pretty complimentary:

At its best, Kumar's reportage has the immediacy and respectful attention to detail of a well-turned Granta essay (it is no surprise to see Ian Jack, Granta's editor, cited in the acknowledgments). Picking his way through lives distorted or destroyed by hatred, Kumar alleviates his own -- and the reader's -- gloom by drawing attention to the fanatics' mordant eccentricities. In the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, where Hindu nationalist cadres called kar-sevaks destroyed the Babri mosque in 1992, Kumar discovers that children now learn math by answering questions like, ''If it takes four kar-sevaks to demolish one mosque, how many does it take to demolish 20?'' He is dismayed that the nationalists have succeeded in making millions of Hindus feel embattled in a country where they form an overwhelming majority. But he is painfully aware that he himself is the anachronism, one of a dwindling band clinging to the secular ideals of India's first prime minister, Jawarharlal Nehru.

To which the joker in me adds: How many kar-sevaks does it take to go screw themselves?

But here is one of Bellague's criticisms:

Kumar the professor has an unfortunate way of intruding on Kumar the reporter. Thus he unnecessarily supplements his own neat description of Hindu political symbolism with the (borrowed) observation that televised Hindu epics had created "a shared symbolic lexicon around which political forces could mobilize communal praxis."

We learn much more when Kumar is describing small things impenetrable to outsiders, like the pungency of a communal slogan, the paradoxes and passions of South Asian cricket and the nuances of an Urdu story. Under the kitchen sink of his parents' home, one memorable childhood vignette runs, there was "a dirty glass and, beside it, a ceramic plate that was white with small pink flowers," reserved for a tubercular uncle. "The only other occasion when the plate and glass were taken out was when a Muslim driver who sometimes ate at our house needed to be fed."

Hm... I for one don't object to "Kumar the professor."

More comments once I've read the book.

Trilling follow-ups

Both Scott Esposito, at Conversational Reading, and Dan Green, at The Reading Experience, have referenced my Lionel Trilling post in the past couple of days. If you're interested, go check out what they have to say.

CNN: "Chapottymouth" on Wolfowitz

Sepoy, of Chapti Mystery, was referenced on CNN yesterday. See the transcript here. It was on the air, so the reporter probably said something like "Chuh-potty," which comes out as "Chapotty" on the transcript:

Here's Sepoy's original post on the subject.

[Wait -- CNN is reading Chapati Mystery...? Someone should start a blog called "Tipu Sultan: Tiger of Mysore" just to get CNN reporters to pronounce "Tipu" and "Mysore":

I also liked Jon Stewart's quip yesterday that, given Wolfowitz's complete lack of qualifications for the presidency of the World Bank, the Bush administration seems to be essentially picking these guys alphabetically (Wolfenson--> Wolfowitz).

The other one, kind of more humorous, over at Chapotty Mystery (ph). And they're talking about -- they call it as the Wolfowitz turns. And they're talking about the "L.A. Times" nomination of Bono, the U2 frontman, as the head of the World Bank. In their eyes, he would be a good choice. And they said that would have the White House scared. And what they're saying is that Bono would have forgiven all loans to Africa or something. And in Wolfowitz, they found someone who won't just raise the interest rate, but he'll invade Africa.

Here's Sepoy's original post on the subject.

[Wait -- CNN is reading Chapati Mystery...? Someone should start a blog called "Tipu Sultan: Tiger of Mysore" just to get CNN reporters to pronounce "Tipu" and "Mysore":

"Tipu" --> "Typo"

"Mysore" --> "Eyesore" ]

I also liked Jon Stewart's quip yesterday that, given Wolfowitz's complete lack of qualifications for the presidency of the World Bank, the Bush administration seems to be essentially picking these guys alphabetically (Wolfenson--> Wolfowitz).

Uncyclopedia; You have two cows

Check out the Uncyclopedia, a parody of Wikipedia.

It looks like Wikipedia, and is an actual Wiki. If I were feeling funny, I would add an entry or two. Or maybe expand the entry on India:

Or I might add to the lucid comparisons of various political ideologies and world religions, under "You have two cows".

Interestingly, Wikipedia has an insightful entry on "You have two cows jokes" here. The highlight is this brilliant paragraph:

Has anyone published a paper on "You have two cows"? It seems like whoever authored this Wikipedia entry is itching to do so...

It looks like Wikipedia, and is an actual Wiki. If I were feeling funny, I would add an entry or two. Or maybe expand the entry on India:

India is a software giant based in Toronto. The company achieved overnight success in 1986 when founder Al Gore invented the internet. Today, India is one of the largest companies in the world, with 1 billion employees and yearly profits of over $10.

Or I might add to the lucid comparisons of various political ideologies and world religions, under "You have two cows".

Interestingly, Wikipedia has an insightful entry on "You have two cows jokes" here. The highlight is this brilliant paragraph:

Because of their freedom and universality of topics, "two cows" jokes are sometimes considered a good example of "cross-cultural humor." They can be concise examples (not necessarily scientific) of how different cultures can express different visions of the same political concept, by paradox, hyperbole, or sarcasm. In practice, most such jokes reflect the views of outsiders to the systems being satirised. In the spirit of finding international common ground, some also see them as humorous manifestations of an underlying general scheme of political science that would compare legal or political concepts, such as the rights of ownership, across cultures around the world.

Has anyone published a paper on "You have two cows"? It seems like whoever authored this Wikipedia entry is itching to do so...

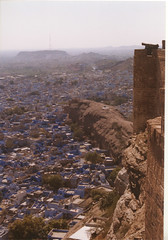

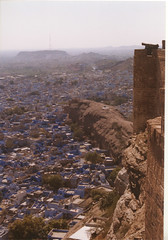

Voyeurism via Flickr: Other People's India Photos

Speaking of marketing Indian tourist sites, I found these photos on Flickr. Just to be clear, these are not my photos! But they are readily available to anyone who does a keyword search for "India" on Flickr. You can also click on the photos to see them in their original context, and find other pictures taken by the same photographers.

Silk shop in Bombay:

Kanyakumari:

Jodhpur fort:

Srinigar-to-Lei:

In the Ellora caves:

From Bhaja Caves, near Pune:

Random guys at the Golden Temple, Amritsar:

I can't wait to go back to India this summer (I hope it works out...)

Silk shop in Bombay:

Kanyakumari:

Jodhpur fort:

Srinigar-to-Lei:

In the Ellora caves:

From Bhaja Caves, near Pune:

Random guys at the Golden Temple, Amritsar:

I can't wait to go back to India this summer (I hope it works out...)

Do English and Hindi/Urdu hurt your ability to learn math?

Sally Thomason, at Language Log, discusses a recent psychological study by a University of Michigan professor that makes the following claim: "the greater transparency of numeral words for 11-19 in East Asian languages accounts in part for young Chinese, Japanese, and Korean students' superior learning of math by comparison to American students." The key seems to be the descriptive power of names for the numbers. As Thomason puts it, "both the ordering of the numerals in the compound English 'teen words (3+10, 4+10, ...) and the semantic opacity of the words eleven and twelve make math learning harder for American first-graders."

Hindi and Urdu actually follow the English system, roughly, in having, non-transparent names for the 'teen' numbers (11-19), so if you follow this psychologist's argument, Hindi and English speaking children should have a tougher time understanding relationships between numbers in grades 1 and 2.

Thomason points out her many objections to the study, which all make sense to me. This seems like a very flawed study of an interesting issue.

My suggestion would be to experimentally teach one group of American first-graders a set of alternate names for 11-19, with new names that actually are transparent. Instead of 'eleven,' and 'twelve,' then, one could try 'teni-one' and 'teni-two'...

Then, compare their scores on a basic math test that only uses numerals (i.e., '11' and not 'eleven'). If there's anything in this theory, the 'teni-one' students should do somewhat better.

Something equivalent could be tried in Hindi: for one group of students, get rid of 'gyara,' 'bara,' etc. Replace with 'ek-das', 'bai-das', or something similar.

Hindi and Urdu actually follow the English system, roughly, in having, non-transparent names for the 'teen' numbers (11-19), so if you follow this psychologist's argument, Hindi and English speaking children should have a tougher time understanding relationships between numbers in grades 1 and 2.

Thomason points out her many objections to the study, which all make sense to me. This seems like a very flawed study of an interesting issue.

My suggestion would be to experimentally teach one group of American first-graders a set of alternate names for 11-19, with new names that actually are transparent. Instead of 'eleven,' and 'twelve,' then, one could try 'teni-one' and 'teni-two'...

Then, compare their scores on a basic math test that only uses numerals (i.e., '11' and not 'eleven'). If there's anything in this theory, the 'teni-one' students should do somewhat better.

Something equivalent could be tried in Hindi: for one group of students, get rid of 'gyara,' 'bara,' etc. Replace with 'ek-das', 'bai-das', or something similar.

The World's Third Poorest Man

Dilip D'Souza has a pithy rejoinder to last week's news that Lakshmi Mittal is the world's third-richest person:

You might want to read the whole thing.

Still, I wonder: If the world's third-richest man is Indian, I feel pretty sure the world's third-poorest man is as well. And the second- and the poorest are probably his neighbours. In fact, I am also pretty sure I saw this third-poorest man yesterday, a sad figure in loose pants and nothing else who, for no clear reason, runs up and down the street near where I live.

You might want to read the whole thing.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)