I've been nominated in three

IndiBloggies categories. It's the Indian version of the more U.S. focused "Bloggies." If you're so inclined, you can vote for me.

Though I'm grateful to be nominated (thanks especially to

Nitin) I must say I do feel these awards things are a little strange. I'm nominated in the same category as

Om Malik, whose blog is a high-tech oriented, "industry" news-aggregator produced by a professional journalist, and

Tsunami Help, which is less a blog than it is a massive news and information aggregator (they've gotten 1.5 million hits in about 10 days!). We are talking about comparing a professionalized apple (Om), a massive humanitarian orange (Tsunami), and in my own personal case, a very small, brainy grape.

Another problem: I hardly write exclusively about things related to India. I'm deeply interested in India, and I spent

two weeks traveling around there this past summer, but I'm firmly attached to the soil (really, the pavement) of the I-95 corridor of the eastern United States. And my range of interests extends to all kinds of non-India-ish things. This is really a cross-category blog, not an "India blog," or an academic blog. (Then again, I am hardly alone in this.)

In lieu of begging for votes, this might be a good opportunity to review what in fact

happened in 2004, which was a very busy year with regard to the Indian Subcontinent and its various diasporas. In addition to the Tsunami, there were historic elections and some major intellectual/academic controversies. There were some depressing anniversaries (Bhopal, Indira Gandhi's assasination, Operation Bluestar, communal violence against Sikhs). And there was

Behzti. Here are some of what I consider to be the better more substantial posts related to Indian politics, literature, and film that I've written from the past year:

I enjoyed talking about

Suketu Mehta's new book,

Maximum City, which is probably the main "must read" book about India published in the U.S. this fall. I responded particularly to Mehta's point about naming and re-naming in "Bombay." Another promising young writer and critic whose work I praised in this blog is

Amitava Kumar.

I closely followed the

Behzti controversy, involving the Sikh community in England. I even posted a

short story I wrote, inspired by the events. On Sikh issues, I also posted a consideration of the 20th anniversay of

Operation Bluestar.

I provided short reviews of

Amitav Ghosh's The Hungry Tide and Hari Kunzru's

Transmission.

My

post on Agha Shahid Ali tried to take an original approach to this sometimes neglected figure.

I've been following the ongoing trials and tribulations of Indian secularism, including

the debates on Triple Talaq, and the

half-hearted reforms of the All-India Muslim Personal Law Board. I've also provided some

background on communalism.

I've been following the implementation of the Hijab and Turban ban in France, and have posted my

critique.

I've talked about a couple of big controversies this past year in the Indian intellectual scene. One is the controversy surrounding Hinduism Studies in the U.S., especially the vehement attack on Wendy Doniger instigated by Rajiv Malhotra. See parts

1 and

2. I've also

responded to the controversy around V.S. Naipaul's support for the Hindu right, which is seemingly out of keeping with his historical self-identification as an atheist and a rootless cosmopolitan.

I followed the upheaval of the Indian elections back in May, and wrote detailed

profiles of Manmohan Singh as well as

President Abdul Kalam.

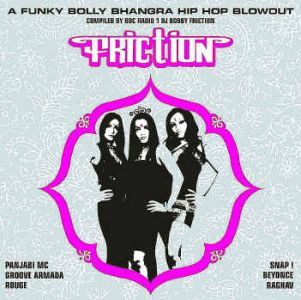

On a lighter (but not that much lighter) note, I've written about my experiences DJing Bhangra parties,

here,

here, and

here.

And amongst my reviews of Hindi films, I put a fair amount of thought into my review of

Yuva, which I think is an extraordinary film by India's best commercial filmmaker.

All in all, a very busy year in Indian subcontinent happenings, and also, therefore, in India-related postings on this blog.

Thanks to everyone out there for reading, linking to me, and commenting.