The world falls forward in the morning, these days.

No rhyme, reason, or rhythm these days.

All that is true may not be expressed, these days.

And all that is desired is expected, one of these days.

Postcolonial/Global literature and film, Modernism, African American literature, and the Digital Humanities.

Is the Indian film industry ready for awards for the best among the worst performances on the lines of Hollywood's Reggie Awards?

For all of you who think that Bollywood is far too 'inspired' by Hollywood, there are still some things from the wild, wild West that clearly do not inspire the folks from India's filmi duniya.

Which is probably why the idea of an awards ceremony to acknowledge the worst performances in filmdom, on the lines of the Reggie Awards in Hollywood, hasn't found favour with the celeb brigade.

While Hollywood takes a tongue-in-cheek look at the best among the worst performances in films, actress Koena Mitra thinks the concept is "disgusting"!

When we explained that we were the mixture of an Indian Jew and an Eastern European Jew, people automatically identified us by the brownness and what made us nonwhite. Their assumptions drew a distinct line between us and them. 'So,' they said, after hearing about the thousands of years of history. 'I guess generations ago, the Jews in India must have intermarried with the Hindus. That's how you have that beautiful brown color.' They even said this laughing admiringly, as though envious of our tan. But in making such a statement, they . . . were also pointing to us as the others and claiming, the skin says it all. We, Ashkenazi Jews, are the pure originals. You, Indian Jews, are mixed products.

He grinned, took a deep puff on his cigarette, thinking. 'Emm. Let's see. Ramle?' I shook my head, surprised to hear this particular city suggested. 'Well, you're Yemenite, right? So I would guess Dimona maybe.'

Now I followed his line of thought. Well-off and educated Israelis of Eastern European descent lived in the nice suburbs. But early on, the Israeli government had filled these particular cities that he was suggesting with large populations of poorer Jewish immigrants from the African and Arab nations. Clumped together, this persecuted a cycle of little money and lots of crime, with not many opportunities in work or eductation to even the score. Because I was brown, this man assumed I had come from that world. Perhaps he even hered me into the class-genus-species of the chach-chach. A chach-chach was usually seen in its natural habitat, making a living by selling sandwiches, cheap barrettes, CDs, and authentic discounted Israeli brassware in one of those neighborhoods or at the central bus station. A chach-chach spoke with guttural slang and listened to the kind of oriental music in which voices wavered and whined and shuddered themselves into a high fever. The male wore gold chains and had slick hair. The female birthed often and early. And she could usually be spotted wearing a plumage of bright lipstick.

"Indian Jews lived as all Jews should have been allowed to live: free, proud, observant, creative and prosperous, self-realized, full contributors to the host community. Then, when twentieth century conditions permitted they returned en masse to Israel, which they had always proclaimed to be their true home despite India's hospitality. The Indian chapter is one of the happiest of the Jewish Diaspora."

Lord God of test-tube and blueprint

Who jointed molecules of dust and shook them till their name was Adam,

Who taught worms and stars how they could live together,

Appear now among the parliaments of conquerors and give instruction to their schemes:

Measure out new liberties so none shall suffer for his father's color or the credo of his choice:

Post proofs that brotherhood is not so wild a dream as those who profit by postponing it pretend:

Sit at the treaty table and convoy the hopes of the little peoples through expected straits,

And press into the final seal a sign that peace will come for longer than posterities can see ahead,

That man unto his fellow man shall be a friend forever. (longer excerpt here)

Here, where last year stood the windrows of the hay

Is now an aviary of such birds

As God had never dreamed of when he made the sky.

Look close, and you will see one now.

They are wheeling it out of the hangar.

Carefully.

Oh, do be careful, gentlemen.

It is so dumbly delicate:

Its fabrics and its metals, its gears, its cylinders, its details,

The million dervishes ready to whirl in its motors,

The guns fore and aft,

The sights, the fins, the fuselage,

The bomb racks and the bombs.

Do not jar them; do not jar them, please.

Be gentle, gentlemen.

This bomber is an instrument of much precision,

a mathematical miracle

As cold and clean and noble as a theorem.

See here: Have you no eye for beauty?

Mark how its nose, be-chromed and tilting toward the heavens

Reflects the morning sun and sniffs the lucent air.

That's all.

That's all the fighting they will care to do.

They have a treaty with the earth

That never will be broken.

They are unbeautiful in death

Their bodies scattered and bestrewn

Amid the shattered theorem.

There is a little oil and blood

Slow draining in the ground.

The metal is still hot, but it will cool.

You need not bother picking up the parts.

The sun has reached meridian.

The day is warm.

There's not a ripple in the air. (link)

I've always thought it hilarious that Indian people chose the most boring, domesticated, compliant and stupid animal on earth to adore, but already I'm seeing cows in a whole different light. These animals clearly know they rule and the like to mess with our heads. The humpbacked bovines step off median strips just as cars are approaching, they stare down drivers daring them to charge, they turn their noses up at passing elephants and camels, and hold huddles at the busiest intersections where they seem to chat away like the bulls of Gary Larson cartoons. It's clear they are enjoying themselves.

But for animals powerful enough to stop traffic and holy enough that they'll never become steak, cows are treated dreadfully. Scrany and sickly, they survive by grazing on garbage that's dumped in plastic bags. The bags collect in their stomachs and strangulate their innards, killing the cows slowly and painfully. Jonathan has already done a story about the urban cowboys of New Delhi who lasso the animals and take them to volunteer vets for operations. Unfortunately the cows are privately owned and once they are restored to health they must be released to eat more plastic.

For a time my cynicism is suspended and I'm in on the group high. The singalong of self-love has created a New Age ring of confidence in the room. Guru Singh oozes happiness in himself, his faith and his music. He gives me a CD of songs he's made with Seal, called Game of Chants, and shows me references by Jane Fonda and Pierce Brosnan. I tell him Courtney Love said sat nam at the MTV awards and showed me some Kundalini Yoga moves when I interviewed her at Triple J [an Australian television variety show], but I can't resist adding that she then put her cigarette out in my coffee. . . . The song and panting stuff may be kind of fun but I'm skeptical of this form of yoga; mainly because the first Sikh guru was critical of the practice and believed service to others was a better way to God. This new version of Sikhism seems to be a synthesis of age-old knowledge and modern self-loving Americanism--its saccharine self-absorbed smugness is a bit much for me.

Best Picture: Brokeback Mountain

Capote

Crash

Good Night, and Good Luck

Munich

First, the United States has no authority to grant such an exemption on its own. The NPT is a treaty signed by 187 nations; it is enforced by the International Atomic Energy Agency; and it is, in effect, administered by the five nations that the treaty recognizes as nuclear powers (the United States, Russia, China, Britain, and France). This point is not a legal nicety. If the United States can cut a separate deal with India, what is to prevent China or Russia from doing the same with Pakistan or Iran? If India demands special treatment on the grounds that it's a stable democracy, what is to keep Japan, Brazil, or Germany from picking up on the precedent?

Second, the India deal would violate not just international agreements but also several U.S. laws regulating the export of nuclear materials.

In other words, an American president who sought to make this deal would, or should, detect a myriad of political actors that might protest or block it—mainly the U.N. Security Council, the Nuclear Suppliers' Group, and the U.S. Congress. Not just as a legal principle but also as a practical consideration, these actors must be notified, cajoled, mollified, or otherwise bargained with if the deal has a chance of coming to life.

The amazing thing is, President Bush just went ahead and made the pledge, without so much as the pretense of consultation—as if all these actors, with their prerogatives over treaties and laws (to say nothing of their concerns for very real dilemmas), didn't exist.

Ironic isn't it, that the only safe public space for a man who has recently been so enthusiastic about India's modernity, should be a crumbling medieval fort?

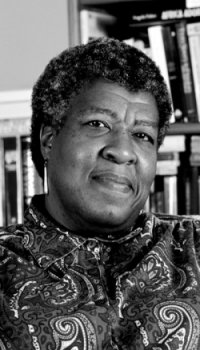

Octavia Butler died last weekend, possibly of a stroke -- though the immediate cause of death was a head wound caused by a bad fall.

Octavia Butler died last weekend, possibly of a stroke -- though the immediate cause of death was a head wound caused by a bad fall. What good is any form of literature to Black people? What good is science fiction's thinking about the present, the future, and the past? What good is its tendency to warn or to consider alternative ways of thinking and doing? What good is its examination of the possible effects of science and technology, or social organization and political direction? At its best, science fiction stimulates imagination and creativity. It gets reader and writer off the beaten track, off the narrow, narrow footpath of what "everyone" is saying, doing, thinking--whoever "everyone" happens to be this year. And what good is all this to Black people? ("Positive Obsession" 134-35)

It may be that when the Indian writer who writes from outside India tries to reflect that world, he is obliged to deal in broken mirrors, some of whose fragments have been irretrievably lost. (Imaginary Homelands)

By blood we are immersed in love of you.

The youth lose their heads for your sake.

I come to you and my heart finds rest.

Away from you, grief clings to my heart like a snake.

I forget the throne of Delhi

When I remember the mountaintops of my Pashtun land.

If I must choose between the world and you,

I shall not hesitate to claim your barren deserts as my own.

--Ahmed Shah Durrani

But the prisoner abuse scandal is primarily an American obsession. In the days following Dave's arrest, not a single person sits down to discuss the situation with my father--unless you count Yossef, who, upon hearing the news, comes upstairs and says, "Hey, they announced the Abdul Wali thing." (It's not that nobody cares; it's just a hardening that accompanies the fact that thousands of Afghans died in prisons during teh Communist and Soviet eras.) I wind up working on a piece for the New York Times Magazine about my experience in the interrogation room, and I have mixed feelings about the assignment. Of all the stories I could pick to tell about Afghanistan right now, I'm not sure if this one would even make the top ten.

As horrible as Abdul Wali's story is -- and as deeply as it's affected me-- a single prisoner's death is hardly the worst of what's going on here this summer. Presidential elections, for instance, are scheduled for the fall, but the registration effort is faltering. The UN's elections workers have already pulled out of the province once and have threatened to do so again if affected by even a single act of violence. In Kunar, where landmines are not hard to come by, the dictate gives a single individual the power to disrupt the upcoming vote. Elsewhere in the country three governors have been forced to flee their posts in recent months. My father now sleeps with a Kalashnikov beside his bed so that he can shoot from the window if the compound comes under attack.

This voyage is our illness: as the long days pass, we grow peevish, apathetic, sullen; we no longer expect, or even wish to recover. Only at moments, when a dolphin leaps or the big real birds from sunken Africa veer round our squat white funnels, we sigh and wince, our bodies gripped by the exquisitely painful pangs of hope. Maybe, after all, we are going to get well.

So from the years their gifts were showered: each

Grabbed at the one it needed to survive;

Bee took the politics that suit a hive,

Trout finned as trout, peach moulded into peach,

And were successful at their first endeavour.

The hour of birth their only time in college,

They were content with their precocious knowledge,

To know their station and be right for ever.

Till, finally, there came a childish creature

On whom the years could model any feature,

Fake, as chance fell, as leopard or a dove,

Who by the gentlest wind was rudely shaken,

Who looked for truth but always was mistaken,

And envied his few friends, and chose his love.

History opposes its grief to our buoyant song,

To our hope its warning. One star has warmed to birth

One puzzled species that has yet to prove its worth:

The quick new West is false, and prodigious but wrong

The flower-like Hundred Families who for so long

In the Eighteen Provinces have modified the earth.

Our global story is not yet completed,

Crime, daring, commerce, chatter will go on,

But, as narrators find their memory gone,

Homeless, disterred, these know themselves defeated.

their doom to bear

Love for some far fobidden country, see

A native disapprove them with a stare

And Freedom's back in every door and tree.