Via Anil Dash, the Anglo-Sikh Heritage Trail.

Maybe for the next time I'm in England with my parents? (since they are likely to be a little underwhelmed at the Tate Modern, or the prospect of Rishi Rich or Raghav live)

Postcolonial/Global literature and film, Modernism, African American literature, and the Digital Humanities.

Hitcount Sociology--The Definitive Amateur Essay on Blogging

I've been thinking about some of the social behaviors associated with blogging lately. I'm not a sociologist, so in some cases I don't have great terminology to describe the phenomena I'm thinking of -– blogroll reciprocity, inflection points, affiliation groups, internet sociality, and changing behaviors. (If anyone can suggest improvements in the vocabulary I'm using below, I would be grateful.)

I also engage a recent paper on blogging by Drezner and Farrell, which was linked to both on Drezner's blog and on Crooked Timber.

Meditating on some of these phenomena has also given me a couple of kooky ideas about how the blog world might continue to evolve. One is an idea I call the “Auto-Affiliation Group,” which is kind of like a group blog defined by a service (rather than the writers themselves). The other, based on popular aggregator services like Bloglines and Kinja, I call the “Re-Aggregator.” Both of these ideas depend on the continued growth of XML/RSS feeds.

Hitcount Sociology

Or: How to Get a Million Hits

Or: BlogStar: The Life and Times of a Cyber-Pundit

Ok, just kidding. In fact, the idea of becoming a famous pundit overnight via blogging is, as most readers must know, really just a myth. Most bloggers –- even the ones who are quick, clever, and dedicated -– end up with a relatively small number of readers and limited growth.

I'm more interested in the space between the lonely solipsist and the massive readership of Kos, Atrios, et al. There are some interesting issues circulating here, in the to-and-fro of linking and counter-linking, and in how people approach the blogs they read. If in publishing there is a category called "mid-list," in blogging there should be a category called mid-count. Most of what I talk about below is the mid-count blog-world.

The attraction of group blogs and comment boards: Are group blogs really blogs? On to the amateur sociology. I should begin with the charms of the group blog, where there is nearly always something new for readers to chew on. Amongst eight bloggers, someone is likely to have come across something interesting this morning (even if I haven't). Also, group blogs usually get many more readers than blogs run purely by individuals. The participants themselves visit multiple times a day, as do a group of regular readers. This "live" quality means that group blogs are likely to have very busy comment boards.

In short, group blogs provide instant access to an internet affiliation group. The ones I know best are Cliopatria (Historians), Crooked Timber (historians, philosophers, and a published poet), Sepia Mutiny (2nd generation Indian-Americans), and The Weblog (a group of semi-academic folks in the mid-west somewhere, most of whom seem to be postmodern Christians).

However, as much as I enjoy visiting them, in my view group blogs operate by different rules than other blogs. I see them as the latest chapter in a long, evolving tradition of internet sociality, which began -- back in the day -- with BBSes, then evolved more recently into web chat rooms, ICQ, Instant Messaging, etc. Group blogs live and die by rules that relate more with those other social systems than regular blogs do. A group blog might have a crisis if a member writes something that causes others to quit. Or it might simply run out of ideas and steam as its members move onto new interests. But the group blogs I've been reading use the diversity of their member's experiences and knowledge-base to create surprising longevity and large-scale popularity.

Blogroll reciprocity. As Henry Farrell and Daniel Drezner pointed out in their paper on blogging, there is an economics of scale in the blog-world, where large blogs can have hundreds or even thousands of in-bound links (or "in-links"). Big blogs are exempt from the rule of blogroll reciprocity; they have in-links which they do not need to return. Moreover, they are able to spread much faster than smaller blogs. In terms of growth, they are up from the inflection point in blogging popularity. Small blogs either hit the inflection point on an upward facing curve, and become 'big', or they hit it flat, and stay where they are or even shrink.

Bartering for links. The existence of this inflection point is interesting from a statistical point of view, but in its emphasis on the probability of making it big, it overlooks what is in my view the most interesting sociological feature of blogging at the present moment, and that is blogroll reciprocity. It's quite simple: if someone links to you, you link back to them, unless you find what they say odious or potentially offensive to the kinds of readers you wish to attract. Links represent recognition and approval. To a small or mid-size blogger, new links (generally discovered through sites like Technorati, or through scrutinizing the "Referrals" in SiteMeter) are encouraging. Upon discovering some new in-links, one feels warm and fuzzy; all is right with the world. The pleasure is surprisingly... ontological.

Affiliation Groups. Some blogrolls represent the blogger's personal affiliation group or groups. Here the criterion for inclusion is not so much reciprocity as belonging: I read these people, and they read me.

These groups are sometimes a bit closed —- especially if the bloggers in question are friends in real life, and the topics discussed are geographically local. But more likely, the group seems closed simply because the conversations are highly involved. To find a point of entry, a visitor needs to spend a fair amount of time navigating the labyrinth of links, reading dozens (hundreds) of posts, scrutinizing blogrolls, and then deciding on key nodes.

The enclosed status of affiliation groups (if it happens) can mean death for the interest-level of the participants. Even if it feels reassuring to see everyone agreeing with everyone else, eventually participants might start to notice that they are living in an echo-chamber. In my view, overly closed blog affiliation groups –- where participants only seriously read and comment on a small number of other participants' work -- miss one of the great merits of the Internet (namely, surprise).

I suspect some of the new affiliation groups I have been seeing amongst humanities academic bloggers this fall might consolidate as they become more established. When they are organized topically (as in the example of feminist humanities academics in the U.S.), I expect to see the formation of some new group blogs, which might immediately raise the visibility of a group. If there is diversity amongst the members of the group, topical group blogs can immediately become major forums for the discussion of major issues.

Idea #1: Auto Affiliation Services. Or there might be services that emerge (a successor to the obsolete blog ring idea) that create group affiliations for casual readers. I already see Bloglines suggesting blogs to add to my blogroll (though their criteria seem to be a little crude at present).

Perhaps it could be done using clever Amazon-like 'taste prediction' technology (perhaps using the TCCI?). Short of that, the job could of course be done by human editors, who might create affiliation groups and suggest "members" to users. It could even be done through a decentralized editorial network: the numbers of votes for certain groups could be used to create aggregates around particular subjects.

Incidentally, this would work better if more blog engines started using Typepad-style "subject" sub-headings, thereby giving more information to the feed aggregators to select by.

Numerical limits of the blogroll/reciprocity system; changing behaviors. Though there is clear benefit in creating links to other blogs on your blog's blogroll (for reasons stated above), that benefit declines as your blogroll continues to grow in size. Once your blogroll tops 50, it's unlikely that the numbers of clicks your link generates will be statistically significant for the other blogger, and it raises questions about whether you really read the blog linked.

And indeed, right now I find it very difficult to read more than about 20-25 blogs regularly. But even this might change. One interesting phenomenon I've noticed in my own reading pattern is that, after nearly 8 months of regular blogging and blog-reading, I now find that the number of blogs I can read/skim/absorb has grown a bit. Perhaps this might happen across the board, as blogging continues to grow, and as the habit of blog-reading becomes naturalized –- a norm, rather than a novelty?

Changing behaviors. However, blog-reading behavior will keep changing as new technologies emerge. Though I have found that I can only follow 10-15 academic blogs regularly if I read them straight off my own blogroll, that number dramatically increases when I use an RSS feeder or an aggregator site like Bloglines or Kinja. It's simply less of a psychic jump to go from one blog to the other if they are all formatted the same. The feeds also load blog pages faster (not an issue on blogspot blogs; sometimes an issue for blogs on private servers).

Aggregator services might decrease casual, intentional visits (i.e., "I wonder what Ph.Diva is up to today"), but they are good in the long run in the sense that they guarantee much more regular readership overall.

Idea #2: Re-aggregators. Another way to make blog-reading more efficient (i.e., when you don't have much time), and also potentially expand the range of blogs you know about, would be for aggregators to determine the most important posts in a define range of blogs, and select a kind of 'best of'. It could be done using somewhat arbitrary criteria (such as the number of other blogs that link to that particular entry).

The advantage here might be the potential to save time involved in running through a long list of feeds. Or perhaps there could be a "surprise me" setting, where the "re-aggregator" might select entries that it thinks you might like based on your current subscription, a set of keywords, and the fact that others have linked to the entry.

Any interest in idea #1 or #2? Any egregious errors? Do I have way too much time on my hands?

I also engage a recent paper on blogging by Drezner and Farrell, which was linked to both on Drezner's blog and on Crooked Timber.

Meditating on some of these phenomena has also given me a couple of kooky ideas about how the blog world might continue to evolve. One is an idea I call the “Auto-Affiliation Group,” which is kind of like a group blog defined by a service (rather than the writers themselves). The other, based on popular aggregator services like Bloglines and Kinja, I call the “Re-Aggregator.” Both of these ideas depend on the continued growth of XML/RSS feeds.

Hitcount Sociology

Or: How to Get a Million Hits

Or: BlogStar: The Life and Times of a Cyber-Pundit

Ok, just kidding. In fact, the idea of becoming a famous pundit overnight via blogging is, as most readers must know, really just a myth. Most bloggers –- even the ones who are quick, clever, and dedicated -– end up with a relatively small number of readers and limited growth.

I'm more interested in the space between the lonely solipsist and the massive readership of Kos, Atrios, et al. There are some interesting issues circulating here, in the to-and-fro of linking and counter-linking, and in how people approach the blogs they read. If in publishing there is a category called "mid-list," in blogging there should be a category called mid-count. Most of what I talk about below is the mid-count blog-world.

The attraction of group blogs and comment boards: Are group blogs really blogs? On to the amateur sociology. I should begin with the charms of the group blog, where there is nearly always something new for readers to chew on. Amongst eight bloggers, someone is likely to have come across something interesting this morning (even if I haven't). Also, group blogs usually get many more readers than blogs run purely by individuals. The participants themselves visit multiple times a day, as do a group of regular readers. This "live" quality means that group blogs are likely to have very busy comment boards.

In short, group blogs provide instant access to an internet affiliation group. The ones I know best are Cliopatria (Historians), Crooked Timber (historians, philosophers, and a published poet), Sepia Mutiny (2nd generation Indian-Americans), and The Weblog (a group of semi-academic folks in the mid-west somewhere, most of whom seem to be postmodern Christians).

However, as much as I enjoy visiting them, in my view group blogs operate by different rules than other blogs. I see them as the latest chapter in a long, evolving tradition of internet sociality, which began -- back in the day -- with BBSes, then evolved more recently into web chat rooms, ICQ, Instant Messaging, etc. Group blogs live and die by rules that relate more with those other social systems than regular blogs do. A group blog might have a crisis if a member writes something that causes others to quit. Or it might simply run out of ideas and steam as its members move onto new interests. But the group blogs I've been reading use the diversity of their member's experiences and knowledge-base to create surprising longevity and large-scale popularity.

Blogroll reciprocity. As Henry Farrell and Daniel Drezner pointed out in their paper on blogging, there is an economics of scale in the blog-world, where large blogs can have hundreds or even thousands of in-bound links (or "in-links"). Big blogs are exempt from the rule of blogroll reciprocity; they have in-links which they do not need to return. Moreover, they are able to spread much faster than smaller blogs. In terms of growth, they are up from the inflection point in blogging popularity. Small blogs either hit the inflection point on an upward facing curve, and become 'big', or they hit it flat, and stay where they are or even shrink.

Bartering for links. The existence of this inflection point is interesting from a statistical point of view, but in its emphasis on the probability of making it big, it overlooks what is in my view the most interesting sociological feature of blogging at the present moment, and that is blogroll reciprocity. It's quite simple: if someone links to you, you link back to them, unless you find what they say odious or potentially offensive to the kinds of readers you wish to attract. Links represent recognition and approval. To a small or mid-size blogger, new links (generally discovered through sites like Technorati, or through scrutinizing the "Referrals" in SiteMeter) are encouraging. Upon discovering some new in-links, one feels warm and fuzzy; all is right with the world. The pleasure is surprisingly... ontological.

Affiliation Groups. Some blogrolls represent the blogger's personal affiliation group or groups. Here the criterion for inclusion is not so much reciprocity as belonging: I read these people, and they read me.

These groups are sometimes a bit closed —- especially if the bloggers in question are friends in real life, and the topics discussed are geographically local. But more likely, the group seems closed simply because the conversations are highly involved. To find a point of entry, a visitor needs to spend a fair amount of time navigating the labyrinth of links, reading dozens (hundreds) of posts, scrutinizing blogrolls, and then deciding on key nodes.

The enclosed status of affiliation groups (if it happens) can mean death for the interest-level of the participants. Even if it feels reassuring to see everyone agreeing with everyone else, eventually participants might start to notice that they are living in an echo-chamber. In my view, overly closed blog affiliation groups –- where participants only seriously read and comment on a small number of other participants' work -- miss one of the great merits of the Internet (namely, surprise).

I suspect some of the new affiliation groups I have been seeing amongst humanities academic bloggers this fall might consolidate as they become more established. When they are organized topically (as in the example of feminist humanities academics in the U.S.), I expect to see the formation of some new group blogs, which might immediately raise the visibility of a group. If there is diversity amongst the members of the group, topical group blogs can immediately become major forums for the discussion of major issues.

Idea #1: Auto Affiliation Services. Or there might be services that emerge (a successor to the obsolete blog ring idea) that create group affiliations for casual readers. I already see Bloglines suggesting blogs to add to my blogroll (though their criteria seem to be a little crude at present).

Perhaps it could be done using clever Amazon-like 'taste prediction' technology (perhaps using the TCCI?). Short of that, the job could of course be done by human editors, who might create affiliation groups and suggest "members" to users. It could even be done through a decentralized editorial network: the numbers of votes for certain groups could be used to create aggregates around particular subjects.

Incidentally, this would work better if more blog engines started using Typepad-style "subject" sub-headings, thereby giving more information to the feed aggregators to select by.

Numerical limits of the blogroll/reciprocity system; changing behaviors. Though there is clear benefit in creating links to other blogs on your blog's blogroll (for reasons stated above), that benefit declines as your blogroll continues to grow in size. Once your blogroll tops 50, it's unlikely that the numbers of clicks your link generates will be statistically significant for the other blogger, and it raises questions about whether you really read the blog linked.

And indeed, right now I find it very difficult to read more than about 20-25 blogs regularly. But even this might change. One interesting phenomenon I've noticed in my own reading pattern is that, after nearly 8 months of regular blogging and blog-reading, I now find that the number of blogs I can read/skim/absorb has grown a bit. Perhaps this might happen across the board, as blogging continues to grow, and as the habit of blog-reading becomes naturalized –- a norm, rather than a novelty?

Changing behaviors. However, blog-reading behavior will keep changing as new technologies emerge. Though I have found that I can only follow 10-15 academic blogs regularly if I read them straight off my own blogroll, that number dramatically increases when I use an RSS feeder or an aggregator site like Bloglines or Kinja. It's simply less of a psychic jump to go from one blog to the other if they are all formatted the same. The feeds also load blog pages faster (not an issue on blogspot blogs; sometimes an issue for blogs on private servers).

Aggregator services might decrease casual, intentional visits (i.e., "I wonder what Ph.Diva is up to today"), but they are good in the long run in the sense that they guarantee much more regular readership overall.

Idea #2: Re-aggregators. Another way to make blog-reading more efficient (i.e., when you don't have much time), and also potentially expand the range of blogs you know about, would be for aggregators to determine the most important posts in a define range of blogs, and select a kind of 'best of'. It could be done using somewhat arbitrary criteria (such as the number of other blogs that link to that particular entry).

The advantage here might be the potential to save time involved in running through a long list of feeds. Or perhaps there could be a "surprise me" setting, where the "re-aggregator" might select entries that it thinks you might like based on your current subscription, a set of keywords, and the fact that others have linked to the entry.

Any interest in idea #1 or #2? Any egregious errors? Do I have way too much time on my hands?

Arun Kolatkar, RIP

See Locana on the poet Arun Kolatkar, who passed away yesterday. I am in the same boat as Locana; I read this interview last month, was vaguely displeased. I thought I would poke around with Kolatkar's work sometime, but then never got around to it.

But Locana: actually it's not too late. You can still write your thing on him anytime you wish...

But Locana: actually it's not too late. You can still write your thing on him anytime you wish...

Manmohan Singh on Charlie Rose: summary of the interview

I've been getting lots of visitors to the site through Google searches for "Charlie Rose Manmohan Singh Interview" or some variant thereof. I had announced it earlier this week.

It's probably too late, but here's my summary of the interview as I saw it. I was taking notes for the first half-hour, but then I got a little tired, so I stopped. All quotes are approximations, not exact.

Incidentally, if you're looking for some more stuff on Manmohan Singh, I blogged a detailed bio of him back in May. Some of the articles and interviews there are still salient.

Charlie Rose's Interview with Manmohan Singh on PBS 9/21/04

The Prime Minister was well-spoken and seemed to be on top of things. Rose praised Manmohan for his erudition (including his occasional literary references to writers like Victor Hugo, as well as his Ox-Bridge education). Rose also noted these accomplishments are all the more impressive given that the fact that Manmohan Singh comes from “rather meager circumstances,” specifically, a small village in what is now Pakistan. Manmohan Singh's accent was not an issue, though I suppose some Americans really un-accustomed to Indian English might have had some difficulty with it. He's not quite as smooth or fluid as real upper-crusty Indo-Anglian types sometimes are (St. Xavier's in Bombay, Stephens in Delhi, etc.).

The interview went on for about 40 minutes, and wasn't cut or interrupted by commercials (for those outside the U.S., Charlie Rose is on American public television, which is commercial-free).

Topics discussed included:

--Relations between India and the U.S. The PM's line was, relations are fortunately improving, though “the best is yet to come." A key point of progress is in the U.S.'s decision to allow India access to information (presumably via purchase from private corporations) about civilian nuclear technology as well as the space program. These are the kinds of things that were discussed when the PM had breakfast with "Dubya."

--India/Pakistan. The PM said that given the extraordinary degree of cultural and personal connection between the two nations, relations need to be driven by more than just the question of Kashmir. There's long way to go, but if confidence-building measures were taken, he said that all possible options are on the table on the Indian side. Here the PM sounded conciliatory, but with a bit of steel in his voice.

--Liberalization. Charlie Rose gave the PM props for his role in liberalization back in 1991, which gave the PM the chance to reiterate his favorite one-liner from Victor Hugo ("No power on earth can stop an idea whose time has come"). Liberalization will continue, though perhaps the PM isn't thinking of it as an urgent priority: "India really is a private sector economy. The public sector is only 30% of the economy."

--The future of the Indian economy. He's optimistic, though he stopped short of bragging.

--On what made him become an economist. He said in school he read a texbook book called Our India by someone named Desani (??), in which there was the statement: “One in five men [on earth] is an Indian. India is a very rich country inhabited by very poor people.”

--Competition between India and China. China has been growing at 7-8% per year. India has been averaging around 6%, but would like to jump up to 7-8% under the government's current Common Minimum Program.

--Why India won't sign the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT):

--On Outsourcing, the PM claimed that it's a predictable phase in the globalization of goods and services, provable by Ricardo's “Comparative advantage Theory.” [That's correct – after 150 years, Ricardo is now a household name]

Charlie Rose outdid him a bit here, suggesting that in fact outsourcing a net-job gainer for the U.S., since the disposable income it produces in the Indian middle-class is spent on consumer goods either produced in the U.S., or that have U.S. Brand names. I was a little annoyed at Rose's one-upmanship here, but then... I guess he meant well.

It's probably too late, but here's my summary of the interview as I saw it. I was taking notes for the first half-hour, but then I got a little tired, so I stopped. All quotes are approximations, not exact.

Incidentally, if you're looking for some more stuff on Manmohan Singh, I blogged a detailed bio of him back in May. Some of the articles and interviews there are still salient.

Charlie Rose's Interview with Manmohan Singh on PBS 9/21/04

The Prime Minister was well-spoken and seemed to be on top of things. Rose praised Manmohan for his erudition (including his occasional literary references to writers like Victor Hugo, as well as his Ox-Bridge education). Rose also noted these accomplishments are all the more impressive given that the fact that Manmohan Singh comes from “rather meager circumstances,” specifically, a small village in what is now Pakistan. Manmohan Singh's accent was not an issue, though I suppose some Americans really un-accustomed to Indian English might have had some difficulty with it. He's not quite as smooth or fluid as real upper-crusty Indo-Anglian types sometimes are (St. Xavier's in Bombay, Stephens in Delhi, etc.).

The interview went on for about 40 minutes, and wasn't cut or interrupted by commercials (for those outside the U.S., Charlie Rose is on American public television, which is commercial-free).

Topics discussed included:

--Relations between India and the U.S. The PM's line was, relations are fortunately improving, though “the best is yet to come." A key point of progress is in the U.S.'s decision to allow India access to information (presumably via purchase from private corporations) about civilian nuclear technology as well as the space program. These are the kinds of things that were discussed when the PM had breakfast with "Dubya."

--India/Pakistan. The PM said that given the extraordinary degree of cultural and personal connection between the two nations, relations need to be driven by more than just the question of Kashmir. There's long way to go, but if confidence-building measures were taken, he said that all possible options are on the table on the Indian side. Here the PM sounded conciliatory, but with a bit of steel in his voice.

--Liberalization. Charlie Rose gave the PM props for his role in liberalization back in 1991, which gave the PM the chance to reiterate his favorite one-liner from Victor Hugo ("No power on earth can stop an idea whose time has come"). Liberalization will continue, though perhaps the PM isn't thinking of it as an urgent priority: "India really is a private sector economy. The public sector is only 30% of the economy."

--The future of the Indian economy. He's optimistic, though he stopped short of bragging.

MS: "I am not an astrologer, but the youthfulness of the working-age population will benefit us in the long run."

--On what made him become an economist. He said in school he read a texbook book called Our India by someone named Desani (??), in which there was the statement: “One in five men [on earth] is an Indian. India is a very rich country inhabited by very poor people.”

--Competition between India and China. China has been growing at 7-8% per year. India has been averaging around 6%, but would like to jump up to 7-8% under the government's current Common Minimum Program.

--Why India won't sign the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT):

MS “The NPT is an unequal treaty. It divides the world into haves and have-nots.

[Charlie Rose prods further, something to the effect of Is the treaty really dead then?]

MS: It is a thing of the past. We have declared a testing moratorium. We have declared no-first-use. We do not allow any of our participation in any proliferation. And we believe our record shows that we should be taken seriously on this.

--On Outsourcing, the PM claimed that it's a predictable phase in the globalization of goods and services, provable by Ricardo's “Comparative advantage Theory.” [That's correct – after 150 years, Ricardo is now a household name]

Charlie Rose outdid him a bit here, suggesting that in fact outsourcing a net-job gainer for the U.S., since the disposable income it produces in the Indian middle-class is spent on consumer goods either produced in the U.S., or that have U.S. Brand names. I was a little annoyed at Rose's one-upmanship here, but then... I guess he meant well.

Democratizing the UN Security Council

See the text of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's address at the UNGA yesterday.

Also see Rajeev's response and Nitin's response to the speech, and the idea of an expanded UN Security Council.

Also see Rajeev's response and Nitin's response to the speech, and the idea of an expanded UN Security Council.

An Introduction to Edward Said, Orientalism, and Postcolonial Literary Studies

REQUEST: If you were assigned this post on Edward Said's "Orientalism" as part of a course, or if you're a teacher who is assigning the below, I would greatly appreciate it if you would leave a comment stating which class and which school below. Or, email me at amardeep [AT] gmail [DOT] com.

It's been about a year since Edward Said passed away.

Recently, there was a panel at Lehigh to talk about his legacy, specifically in the spheres of his contribution to literary studies, the representation of Islam, as well as his political advocacy. I was on the panel to talk about literary studies, especially his books Orientalism (1978) and Culture and Imperialism (1993).

Preparing a presentation gave me an opportunity to look at some Said essays on literature I hadn't ever read (see for instance this at LRB; or this at Al-Ahram). I was also particularly impressed by the Said resources at www.edwardsaid.org. There are dozens and dozens of essays by Said linked there, as well as a great many "tribute" essays written by critics all around the world, immediately after his passing. I highly recommend it.

An Introduction to Edward Said, Orientalism, and Postcolonial Literary Studies

(For a very general audience; notes for a presentation given at Lehigh University on 9/23/04)

Basic Bio: "Edward Said was born in Jerusalem in 1935 and was for many years America’s foremost spokesman for the Palestinian cause. His writings have been translated into 26 languages, including his most influential book, Orientalism (1978), an examination of the way the West perceives the Islamic world. Much of his writing beyond literary and cultural criticism is inspired by his passionate advocacy of the Palestinian cause, including The Question of Palestine, (1979), Covering Islam (1981), After the Last Sky (1986) and Blaming the Victims (1988). . . . He went to a New England boarding school, undergraduate years at Princeton and graduate study at Harvard." (from the Columbia University website)

Orientalism

Edward Said's signature contribution to academic life is the book Orientalism. It has been influential in about half a dozen established disciplines, especially literary studies (English, comparative literature), history, anthropology, sociology, area studies (especially middle east studies), and comparative religion. However, as big as Orientalism was to academia, Said’s thoughts on literature and art continued to evolve over time, and were encapsulated in Culture and Imperialism (1993), a book which appeared nearly 15 years after Orientalism (1978). Put highly reductively, the development of his thought can be understood as follows: Said’s early work began with a gesture of refusal and rejection, and ended with a kind of ambivalent acceptance. If Orientalism questioned a pattern of misrepresentation of the non-western world, Culture and Imperialism explored with a less confrontational tone the complex and ongoing relationships between east and west, colonizer and colonized, white and black, and metropolitan and colonial societies.

Said directly challenged what Euro-American scholars traditionally referred to as "Orientalism." Orientalism is an entrenched structure of thought, a pattern of making certain generalizations about the part of the world known as the 'East'. As Said puts it:

Just to be clear, Said didn't invent the term 'Orientalism'; it was a term used especially by middle east specialists, Arabists, as well as many who studied both East Asia and the Indian subcontinent. The vastness alone of the part of the world that European and American scholars thought of as the "East" should, one imagines, have caused some one to think twice. But for the most part, that self-criticism didn’t happen, and Said argues that the failure there –- the blind spot of orientalist thinking –- is a structural one.

The stereotypes assigned to Oriental cultures and "Orientals" as individuals are pretty specific: Orientals are despotic and clannish. They are despotic when placed in positions of power, and sly and obsequious when in subservient positions. Orientals, so the stereotype goes, are impossible to trust. They are capable of sophisticated abstractions, but not of concrete, practical organization or rigorous, detail-oriented analysis. Their men are sexually incontinent, while their women are locked up behind bars. Orientals are, by definition, strange. The best summary of the Orientalist mindset would probably be: “East is east and west is west, and never the twain shall meet” (Rudyard Kipling).

In his book, Said asks: but where is this sly, devious, despotic, mystical Oriental? Has anyone ever met anyone who meets this description in all particulars? In fact, this idea of the Oriental is a particular kind of myth produced by European thought, especially in and after the 18th century. In some sense his book Orientalism aims to dismantle this myth, but more than that Said's goal is to identify Orientalism as a discourse.

From Myth to Discourse. The oriental is a myth or a stereotype, but Said shows that the myth had, over the course of two centuries of European thought, come to be thought of as a kind of systematic knowledge about the East. Because the myth masqueraded as fact, the results of studies into eastern cultures and literature were often self-fulfilling. It was accepted as a common fact that Asians, Arabs, and Indians were mystical religious devotees incapable of rigorous rationality. It is unsurprising, therefore that so many early European studies into, for instance, Persian poetry, discovered nothing more or less than the terms of their inquiry were able to allow: mystical religious devotion and an absence of rationality.

Political Dominance. Said showed that the myth of the Oriental was possible because of European political dominance of the Middle East and Asia. In this aspect of his thought he was strongly influenced by the French philosopher Michel Foucault. The influence from Foucault is wide-ranging and thorough, but it is perhaps most pronounced when Said argues that Orientalism is a full-fledged discourse, not just a simple idea, and when he suggests that all knowledge is produced in situations of unequal relations of power. In short, a person who dominates another is the only one in a position to write a book about it, to establish it, to define it. It’s not a particular moral failing that the stereotypical failing defined as Orientalism emerged in western thinking, and not somewhere else.

Post-colonial Criticism

Orientalism was a book about a particular pattern in western thought. It was not, in and of itself, an evaluation of the importance of that thought. It was written before the peak of the academic ‘culture wars’, when key words like relativism, pluralism, and multiculturalism would be the order of the day. Said has often been lumped in with relativists and pluralists, but in fact he doesn’t belong there.

In his later literary and cultural work, especially in Culture and Imperialism Said generally avoided the language of confrontation. Where others have angrily rejected the literary heritage of the Western Canon, Said, has instead embraced it, albeit ambivalently. Where others denounced Joseph Conrad and Rudyard Kipling as racist dead white men, Said wrote careful reappraisals of their works, focusing on their representations of India and Africa respectively. Said did not apologize for, for instance, Joseph Conrad’s image of the Congo as an essentially corrupting place inhabited by ruthless cannibals. But Said did acknowledge Conrad’s gift for style, and explored its implications: Conrad was sophisticated enough to sense that he did indeed have a blind spot. Conrad recognized that the idea of imperialism was an illusion, built entirely on a very fragile mythic rhetoric. You see some of this in the famous quote from Heart of Darkness:

The lines are spoken by the sailor Marlowe, who was in effect an observer-participant to the scene of Kurtz’s fatal breakdown in the upper Congo. He is a veteran, of the colonial system, and this is the first place where his views become apparent. Like many others in his trade, Marlowe was in fact ambivalent about what was, in effect, his job. He knows the violence of it and the potential evil of it, but he still tries to justify it through recourse to the "idea at the back of it." But even more puzzling: that "idea at the back of it" is not an idea of reason, or human rights, or technology (or the pursuit of weapons of mass destruction). The idea is something to "bow down before, offer a sacrifice to..." The desire to conquer the earth, in short, is as irrational a desire as any.

Said refers to this passage a few times in his essays. One such response is as follows, where Said sketches an account of the political conditions that made imperialism possible in England and France, as well as general readings of several works of literature. I quote at length because this is a perfect example of Said’s ability to blend political/historical analysis with literary criticism:

A final point, about postcolonial studies. The development of Said’s ideas about literature and art paralleled those of the field of post-colonial criticism as a whole. It began in anger – Frantz Fanon, Aime Cesaire, Malcolm X. And it has ended up in a rather different place, embraced in the very academic settings that once might have laughed at the very notion of a canonical body of, say, African Literature.

That means that nativism cannot be an effective answer to western hegemony (later he gets more specific: "Afrocentrism is as flawed as Eurocentrism"). There’s no simple way to achieve decolonization, just as (in the more limited context of the United States), there’s no simple way for anyone to disentangle him or herself from the effects of racism.

But it also means that, in many respects, colonialism is still with us. It was through the colonial system that most of the national borders in Africa and Asia were drawn up, in many cases arbitrarily. But more than that are the effects of colonial language, the colonial state bureaucracy, and especially colonial attitudes to things like economic development.

It's been about a year since Edward Said passed away.

Recently, there was a panel at Lehigh to talk about his legacy, specifically in the spheres of his contribution to literary studies, the representation of Islam, as well as his political advocacy. I was on the panel to talk about literary studies, especially his books Orientalism (1978) and Culture and Imperialism (1993).

Preparing a presentation gave me an opportunity to look at some Said essays on literature I hadn't ever read (see for instance this at LRB; or this at Al-Ahram). I was also particularly impressed by the Said resources at www.edwardsaid.org. There are dozens and dozens of essays by Said linked there, as well as a great many "tribute" essays written by critics all around the world, immediately after his passing. I highly recommend it.

An Introduction to Edward Said, Orientalism, and Postcolonial Literary Studies

(For a very general audience; notes for a presentation given at Lehigh University on 9/23/04)

Basic Bio: "Edward Said was born in Jerusalem in 1935 and was for many years America’s foremost spokesman for the Palestinian cause. His writings have been translated into 26 languages, including his most influential book, Orientalism (1978), an examination of the way the West perceives the Islamic world. Much of his writing beyond literary and cultural criticism is inspired by his passionate advocacy of the Palestinian cause, including The Question of Palestine, (1979), Covering Islam (1981), After the Last Sky (1986) and Blaming the Victims (1988). . . . He went to a New England boarding school, undergraduate years at Princeton and graduate study at Harvard." (from the Columbia University website)

Orientalism

Edward Said's signature contribution to academic life is the book Orientalism. It has been influential in about half a dozen established disciplines, especially literary studies (English, comparative literature), history, anthropology, sociology, area studies (especially middle east studies), and comparative religion. However, as big as Orientalism was to academia, Said’s thoughts on literature and art continued to evolve over time, and were encapsulated in Culture and Imperialism (1993), a book which appeared nearly 15 years after Orientalism (1978). Put highly reductively, the development of his thought can be understood as follows: Said’s early work began with a gesture of refusal and rejection, and ended with a kind of ambivalent acceptance. If Orientalism questioned a pattern of misrepresentation of the non-western world, Culture and Imperialism explored with a less confrontational tone the complex and ongoing relationships between east and west, colonizer and colonized, white and black, and metropolitan and colonial societies.

Said directly challenged what Euro-American scholars traditionally referred to as "Orientalism." Orientalism is an entrenched structure of thought, a pattern of making certain generalizations about the part of the world known as the 'East'. As Said puts it:

“Orientalism was ultimately a political vision of reality whose structure promoted the difference between the familiar (Europe, West, "us") and the strange (the Orient, the East, "them").”

Just to be clear, Said didn't invent the term 'Orientalism'; it was a term used especially by middle east specialists, Arabists, as well as many who studied both East Asia and the Indian subcontinent. The vastness alone of the part of the world that European and American scholars thought of as the "East" should, one imagines, have caused some one to think twice. But for the most part, that self-criticism didn’t happen, and Said argues that the failure there –- the blind spot of orientalist thinking –- is a structural one.

The stereotypes assigned to Oriental cultures and "Orientals" as individuals are pretty specific: Orientals are despotic and clannish. They are despotic when placed in positions of power, and sly and obsequious when in subservient positions. Orientals, so the stereotype goes, are impossible to trust. They are capable of sophisticated abstractions, but not of concrete, practical organization or rigorous, detail-oriented analysis. Their men are sexually incontinent, while their women are locked up behind bars. Orientals are, by definition, strange. The best summary of the Orientalist mindset would probably be: “East is east and west is west, and never the twain shall meet” (Rudyard Kipling).

In his book, Said asks: but where is this sly, devious, despotic, mystical Oriental? Has anyone ever met anyone who meets this description in all particulars? In fact, this idea of the Oriental is a particular kind of myth produced by European thought, especially in and after the 18th century. In some sense his book Orientalism aims to dismantle this myth, but more than that Said's goal is to identify Orientalism as a discourse.

From Myth to Discourse. The oriental is a myth or a stereotype, but Said shows that the myth had, over the course of two centuries of European thought, come to be thought of as a kind of systematic knowledge about the East. Because the myth masqueraded as fact, the results of studies into eastern cultures and literature were often self-fulfilling. It was accepted as a common fact that Asians, Arabs, and Indians were mystical religious devotees incapable of rigorous rationality. It is unsurprising, therefore that so many early European studies into, for instance, Persian poetry, discovered nothing more or less than the terms of their inquiry were able to allow: mystical religious devotion and an absence of rationality.

Political Dominance. Said showed that the myth of the Oriental was possible because of European political dominance of the Middle East and Asia. In this aspect of his thought he was strongly influenced by the French philosopher Michel Foucault. The influence from Foucault is wide-ranging and thorough, but it is perhaps most pronounced when Said argues that Orientalism is a full-fledged discourse, not just a simple idea, and when he suggests that all knowledge is produced in situations of unequal relations of power. In short, a person who dominates another is the only one in a position to write a book about it, to establish it, to define it. It’s not a particular moral failing that the stereotypical failing defined as Orientalism emerged in western thinking, and not somewhere else.

Post-colonial Criticism

Orientalism was a book about a particular pattern in western thought. It was not, in and of itself, an evaluation of the importance of that thought. It was written before the peak of the academic ‘culture wars’, when key words like relativism, pluralism, and multiculturalism would be the order of the day. Said has often been lumped in with relativists and pluralists, but in fact he doesn’t belong there.

In his later literary and cultural work, especially in Culture and Imperialism Said generally avoided the language of confrontation. Where others have angrily rejected the literary heritage of the Western Canon, Said, has instead embraced it, albeit ambivalently. Where others denounced Joseph Conrad and Rudyard Kipling as racist dead white men, Said wrote careful reappraisals of their works, focusing on their representations of India and Africa respectively. Said did not apologize for, for instance, Joseph Conrad’s image of the Congo as an essentially corrupting place inhabited by ruthless cannibals. But Said did acknowledge Conrad’s gift for style, and explored its implications: Conrad was sophisticated enough to sense that he did indeed have a blind spot. Conrad recognized that the idea of imperialism was an illusion, built entirely on a very fragile mythic rhetoric. You see some of this in the famous quote from Heart of Darkness:

The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much. What redeems it is the idea only. An idea at the back of it; not a sentimental pretence but an idea; and an unselfish belief in the idea -- something you can set up, and bow down before, and offer a sacrifice to. . . ."

The lines are spoken by the sailor Marlowe, who was in effect an observer-participant to the scene of Kurtz’s fatal breakdown in the upper Congo. He is a veteran, of the colonial system, and this is the first place where his views become apparent. Like many others in his trade, Marlowe was in fact ambivalent about what was, in effect, his job. He knows the violence of it and the potential evil of it, but he still tries to justify it through recourse to the "idea at the back of it." But even more puzzling: that "idea at the back of it" is not an idea of reason, or human rights, or technology (or the pursuit of weapons of mass destruction). The idea is something to "bow down before, offer a sacrifice to..." The desire to conquer the earth, in short, is as irrational a desire as any.

Said refers to this passage a few times in his essays. One such response is as follows, where Said sketches an account of the political conditions that made imperialism possible in England and France, as well as general readings of several works of literature. I quote at length because this is a perfect example of Said’s ability to blend political/historical analysis with literary criticism:

But there's more than that to imperialism. There was a commitment to imperialism over and above profit, a commitment in constant circulation and recirculation which on the one hand allowed decent men and women from England or France, from London or Paris, to accept the notion that distant territories and their native peoples should be subjugated and, on the other hand, replenished metropolitan energies so that these decent people could think of the empire as a protracted, almost metaphysical obligation to rule subordinate, inferior or less advanced peoples. We mustn't forget, and this is a very important aspect of my topic, that there was very little domestic resistance inside Britain and France. There was a kind of tremendous unanimity on the question of having an empire. There was very little domestic resistance to imperial expansion during the nineteenth century, although these empires were very frequently established and maintained under adverse and even disadvantageous conditions. Not only were immense hardships in the African wilds or wastes, the "dark continent," as it was called in the latter part of the nineteenth century, endured by the white colonizers, but there was always the tremendously risky physical disparity between a small number of Europeans at a very great distance from home and a much larger number of natives on their home territory. In India, for instance, by the 1930s, a mere 4,000 British civil servants, assisted by 60,000 soldiers and 90,000 civilians, had billeted themselves upon a country of 300,000,000 people. The will, self-confidence, even arrogance necessary to maintain such a state of affairs could only be guessed at. But as one can see in the texts of novels like Forster's Passage to India or Kipling's Kim, these attitudes are at least as significant as the number of people in the army or civil service or the millions of pounds that England derived from India.

For the enterprise of empire depends upon the idea of having an empire, as Joseph Conrad so powerfully seems to have realized in Heart of Darkness. He says that the difference between us in the modern period, the modern imperialists, and the Romans is that the Romans were there just for the loot. They were just stealing. But we go there with an idea. He was thinking, obviously, of the idea, for instance in Africa, of the French and the Belgians that when you go to these continents you're not just robbing the people of their ivory and slaves and so on. You are improving them in some way. I'm really quite serious. The idea, for example, of the French empire was that France had a "mission civilisatrice," that it was there to civilize the natives. It was a very powerful idea. Obviously, not so many of the natives believed it, but the French believed that that was what they were doing.

The idea of having an empire is very important, and that is the central feature that I am interested in. All kinds of preparations are made for this idea within a culture and then, in turn and in time, imperialism acquires a kind of coherence, a set of experiences and a presence of ruler and ruled alike within the culture. (see http://www.zmag.org/zmag/articles/barsaid.htm)

A final point, about postcolonial studies. The development of Said’s ideas about literature and art paralleled those of the field of post-colonial criticism as a whole. It began in anger – Frantz Fanon, Aime Cesaire, Malcolm X. And it has ended up in a rather different place, embraced in the very academic settings that once might have laughed at the very notion of a canonical body of, say, African Literature.

Post-colonial criticism, which began under the combative spiritual aegis of [Frantz] Fanon and [Aime] Césaire, went further than either of them in showing the existence of what in Culture and Imperialism I called 'overlapping territories' and 'intertwined histories'. Many of us who grew up in the colonial era were struck by the fact that even though a hard and fast line separated colonizer from colonized in matters of rule and authority (a native could never aspire to the condition of the white man), the experiences of ruler and ruled were not so easily disentangled. (from the London Review of Books: http://www.lrb.co.uk/v25/n06/said01_.html)

That means that nativism cannot be an effective answer to western hegemony (later he gets more specific: "Afrocentrism is as flawed as Eurocentrism"). There’s no simple way to achieve decolonization, just as (in the more limited context of the United States), there’s no simple way for anyone to disentangle him or herself from the effects of racism.

But it also means that, in many respects, colonialism is still with us. It was through the colonial system that most of the national borders in Africa and Asia were drawn up, in many cases arbitrarily. But more than that are the effects of colonial language, the colonial state bureaucracy, and especially colonial attitudes to things like economic development.

U.S. 0 for 5000 on Terrorist Convictions

According to Alternet, the only foreign nationals convicted as 'terrorists' have now had their convictions overturned. This brings the U.S.'s conviction of 'terrorists' under the Patriot Act back to 0.

Among the gems of this case are these details:

To quote Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, and Cole Porter: "Well, did you evah. What a swell party this is!"

(Via Keywords)

Among the gems of this case are these details:

The Detroit case was extremely weak from the outset. The government could never specify exactly what terrorist activity was allegedly being planned and never offered any evidence linking the defendants to al Qaeda. Its case consisted almost entirely of a pair of sketches and a videotape, described by an FBI agent as "casing materials" for a terrorist plot, and the testimony of a witness of highly dubious reliability seeking a generous plea deal. It now turns out that the prosecution failed to disclose to the defense evidence that other government experts did not consider the sketches and videotape to be terrorist casing materials at all and that the government's key witness had admitted to lying.

To quote Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, and Cole Porter: "Well, did you evah. What a swell party this is!"

(Via Keywords)

Kahaniwallah: New Githa Hariharan children's book

I received a publication announcement for a new book by Githa Hariharan, a well-known novelist and teacher in Delhi. (If you're looking for a sophisticated treatment of gender/sexuality issues in a time of ethno-religious warfare -- and aren't we all -- read In Times of Siege. It's her best book).

Hariharan's new book is called The Winning Team, and it has illustrations by Taposhi Ghoshal. Here is the description (I edited out some hokey-sounding stuff):

Looks fun. Anyone out there have kids?

BTW I once knew a bald babu from Krishnapur -- hell of a guy. Always on the ball.

Hariharan's new book is called The Winning Team, and it has illustrations by Taposhi Ghoshal. Here is the description (I edited out some hokey-sounding stuff):

Once there was a storyteller who was out of work. He didn't know how it had happened - but he no longer had anyone to tell his stories to.

But luckily for Kahani Bhai (also called Bhai K), he finds the best audience in the world - the winning team of friends, Nasira, Gopal, Akbari, Veer, Dulari and Ram. And like magic, or like the kahaniwala he really is, all the old stories crowding Bhai K's mind, all the happy, clever and funny faces - of Tenali Raman, Naseeruddin Hodja, Gopal Bhar, Birbal - change into real people as he tells the stories.

Ten stories of the different kinds of people the winning team meet as they get into the stories, from Ramu the Boy Wonder, to the hill-moving Hodja, to the bald babus of Krishnapur, to Nasser the Ferryboy.

Looks fun. Anyone out there have kids?

BTW I once knew a bald babu from Krishnapur -- hell of a guy. Always on the ball.

Academic blogging comes of age

Via Chuck Tryon, this piece in the Guardian about academic blogging. The thing seems to be taking off!

Sam Harris: militant atheism

I recently came across Natalie Angier's review of Sam Harris's book The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason. It has stuff like this:

In my view, those sorts of pot-shots don't do anyone any good.

But Angier argues that Harris is going a little further than that. The point is not his snide comments about religious faiths, but rather his right to make them. Harris feels that this right is in jeopardy:

I don't think this is true. People in mainstream venues do criticize some religious beliefs quite openly, especially when those beliefs are seen as pernicious to human rights (for instance, the idea that God is against abortion and homosexuality can be widely and readily criticized).

Harris is worried that believers in the "metaphysics of martyrdom" (read: Muslims) will destroy the world. It is necessary to challenge their beliefs for the dangers they pose to us:

I'll go check out the book in the bookstore, but I am very skeptical of all this. It seems like Harris has a rather over-simplified (and Christian-centric) view of religion. I also wonder if he has any interest in whether his words will have an effect. Simply equating religious beliefs with irrationality is not going to get you anywhere, anyhow. (To loosely quote the Beatles)

''We have names for people who have many beliefs for which there is no rational justification. When their beliefs are extremely common, we call them 'religious'; otherwise, they are likely to be called 'mad,' 'psychotic' or 'delusional.' '' To cite but one example: ''Jesus Christ -- who, as it turns out, was born of a virgin, cheated death and rose bodily into the heavens -- can now be eaten in the form of a cracker. A few Latin words spoken over your favorite Burgundy, and you can drink his blood as well. Is there any doubt that a lone subscriber to these beliefs would be considered mad?'' The danger of religious faith, he continues, ''is that it allows otherwise normal human beings to reap the fruits of madness and consider them holy.''

In my view, those sorts of pot-shots don't do anyone any good.

But Angier argues that Harris is going a little further than that. The point is not his snide comments about religious faiths, but rather his right to make them. Harris feels that this right is in jeopardy:

''Criticizing a person's faith is currently taboo in every corner of our culture. On this subject, liberals and conservatives have reached a rare consensus: religious beliefs are simply beyond the scope of rational discourse. Criticizing a person's ideas about God and the afterlife is thought to be impolitic in a way that criticizing his ideas about physics or history is not.''

I don't think this is true. People in mainstream venues do criticize some religious beliefs quite openly, especially when those beliefs are seen as pernicious to human rights (for instance, the idea that God is against abortion and homosexuality can be widely and readily criticized).

Harris is worried that believers in the "metaphysics of martyrdom" (read: Muslims) will destroy the world. It is necessary to challenge their beliefs for the dangers they pose to us:

''We can no longer ignore the fact that billions of our neighbors believe in the metaphysics of martyrdom, or in the literal truth of the book of Revelation,'' he writes, ''because our neighbors are now armed with chemical, biological and nuclear weapons.''

Harris reserves particular ire for religious moderates, those who ''have taken the apparent high road of pluralism, asserting the equal validity of all faiths'' and who ''imagine that the path to peace will be paved once each of us has learned to respect the unjustified beliefs of others.'' Religious moderates, he argues, are the ones who thwart all efforts to criticize religious literalism. By preaching tolerance, they become intolerant of any rational discussion of religion and ''betray faith and reason equally.''

I'll go check out the book in the bookstore, but I am very skeptical of all this. It seems like Harris has a rather over-simplified (and Christian-centric) view of religion. I also wonder if he has any interest in whether his words will have an effect. Simply equating religious beliefs with irrationality is not going to get you anywhere, anyhow. (To loosely quote the Beatles)

Manmohan Singh on Charlie Rose tonight

The Telegraph reports that Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh is sitting down for an interview with Charlie Rose while he is in New York for the UNGA.

According to the PBS website, the interview will air tonight. My local PBS channel will broadcast it at 11:30pm. You can find out when it is on here.

According to the PBS website, the interview will air tonight. My local PBS channel will broadcast it at 11:30pm. You can find out when it is on here.

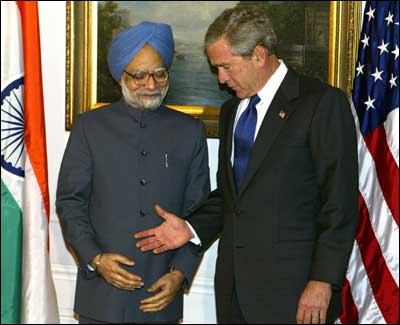

Provide a caption for this photo

Manmohan: "Do I have to? It doesn't even look especially clean."

Dubya: "That is my hand. My hand in. Ineluctable modality of the visible: at least that if no more, thought through my eyes. Signatures of all things I am here to read, seaspawn and sewrack, the nearing tide, that rusty boot. ... If you can put your five fingers through it it is a gate, if not a door. Shut your eyes and see."

[Image source: AFP]

Anyone got a better one?

Human Rights in India: Still a Problem

An exchange with one of the 'Gene Expression' people (think: George Will + Dartmouth Review) on Sepia Mutiny has me riled up about the question of human rights in India.

Specifically, what I have to say is this: there is a problem. It is serious. I'm not sure what awaits Paramvir Singh Chattwal, an asylum seeker in Florida who faces deportation after he failed to show up for a hearing. He may be detained by Indian police upon return to India, or he may not. He may be tortured yet further or even killed, or not. I don't know, and I don't think anyone knows.

But there are two things I think people need to remember:

1) Being detained by the Indian police is a very dangerous proposition, even to this day. A human rights activist cited in a recent Washington Post article claimed that there 1,300 people died in police custody in 2002. (I linked to that article in an earlier post)

2) The Indian police has a history of human rights violations it has never been held accountable for. Nor has it ever directly acknowledged that there is a problem.

On this note, let me offer a link to a blog produced by an acquaintance of mine named Jaskaran Kaur. Jaskaran has a Harvard law degree, and lives in Boston. Earlier she worked with an India-based activist named Ram Narayan Kumar to push through full documentation of the disappearances of Sikhs in Punjab. They performed many, many interviews with surviving family members of the 2000+ Sikh men who had been 'disappeared' in the 1980s, and kept the attempt to hold the government accountable alive. Some of the fruits of this research is available at this website. Further documentation is in a book published by the CCDP called Reduced to Ashes.

The point is, this stuff happened. Many, many people have been summarily killed in the interest of India's law and order. I don't know Paramvir Singh Chattwal from adam, and can't say whether I believe him. But if he says he was tortured and still has the scars from stab wounds on his body, I take that seriously. If he's being deported and sent back, that's a concern.

I should be clear: I am not sympathetic with those who want parts of India to secede in the interest of a dubious ethno-religious purity. I love India; I think it's an amazing country. I spend a lot of my professional energy trying to convince people -- colleagues, students, readers -- to take notice of it.

I'm only making these criticisms because I think India would be a much better place if the criminal justice system were radically reformed, if transparency were introduced, and if law-enforcement officers who've crossed the line were held to account for their actions. The first step is to admit what happened. The second is to recognize that it still happens (often for non-ideological reasons now).

But those are steps some people do not seem willing to take.

Specifically, what I have to say is this: there is a problem. It is serious. I'm not sure what awaits Paramvir Singh Chattwal, an asylum seeker in Florida who faces deportation after he failed to show up for a hearing. He may be detained by Indian police upon return to India, or he may not. He may be tortured yet further or even killed, or not. I don't know, and I don't think anyone knows.

But there are two things I think people need to remember:

1) Being detained by the Indian police is a very dangerous proposition, even to this day. A human rights activist cited in a recent Washington Post article claimed that there 1,300 people died in police custody in 2002. (I linked to that article in an earlier post)

2) The Indian police has a history of human rights violations it has never been held accountable for. Nor has it ever directly acknowledged that there is a problem.

On this note, let me offer a link to a blog produced by an acquaintance of mine named Jaskaran Kaur. Jaskaran has a Harvard law degree, and lives in Boston. Earlier she worked with an India-based activist named Ram Narayan Kumar to push through full documentation of the disappearances of Sikhs in Punjab. They performed many, many interviews with surviving family members of the 2000+ Sikh men who had been 'disappeared' in the 1980s, and kept the attempt to hold the government accountable alive. Some of the fruits of this research is available at this website. Further documentation is in a book published by the CCDP called Reduced to Ashes.

The point is, this stuff happened. Many, many people have been summarily killed in the interest of India's law and order. I don't know Paramvir Singh Chattwal from adam, and can't say whether I believe him. But if he says he was tortured and still has the scars from stab wounds on his body, I take that seriously. If he's being deported and sent back, that's a concern.

I should be clear: I am not sympathetic with those who want parts of India to secede in the interest of a dubious ethno-religious purity. I love India; I think it's an amazing country. I spend a lot of my professional energy trying to convince people -- colleagues, students, readers -- to take notice of it.

I'm only making these criticisms because I think India would be a much better place if the criminal justice system were radically reformed, if transparency were introduced, and if law-enforcement officers who've crossed the line were held to account for their actions. The first step is to admit what happened. The second is to recognize that it still happens (often for non-ideological reasons now).

But those are steps some people do not seem willing to take.

Outsourcing: further updates (but no potato)

Further follow-up from Drezner on Samuelson/Bhagwati. Drezner has now read everything on the subject, including Arvind Panagariya's response to Samuelson. BUT he doesn't indicate anywhere that he's read the article itself!

Somebody has to have the potato.

And also see the comments on Kaushik's blog. They're very helpful.

Somebody has to have the potato.

And also see the comments on Kaushik's blog. They're very helpful.

Alan Wolfe on why the Democrats lose the 'God' vote

Alan Wolfe has a piece in the September 19 Boston Globe on religion and political parties. Wolfe has been writing a lot recently on the politicization of religion in America, and claims that the Democrats could -- and perhaps should -- win the 'God' vote in America. They are not especially irreligious, especially if you consider how religious African American democrats are. And it's not like the Republican leadership is composed of church-goin' ordinary folk. No matter how often George W. Bush puts on his cowboy hat, remember: he went to Yale, he went to Yale, he went to Yale! And economically... well, readers are probably well familiar with the problem of people voting against their economic interests.

The recent history of American secularization. From the early 1960s to 1994, most liberals have believed in what I call strong secularism, which is both cultural and political. In this strong secularism, religion is supposed to play a small or nonexistent role in public life, while the government is required to uphold strong church-state separation. As Wolfe points out, liberals during this period found their views on religion in cultural life ratified and reinforced by the kinds of decisions the Supreme Court was making on things like prayer in school and (especially) abortion.

What does secularism mean in the era of Promise Keepers and Christian Rock? But strong secularism was dealt a severe blow in 1994, with the Republican revolution. For a number of reasons, liberal democrats are being forced to admit that cultural secularism has become a minority position. But secularism as a legal and judicial concept has remained very much in place. The Republicans have exploited the gap between the two concepts of secularism to great advantage, in part by blurring the line between them. The Democrats' failure to win the God vote perhaps has something to do with their failure to soften strong secularism.

The Democrats' own litmus test. The Democrats have also sometimes made poor decisions on how to respond. For instance, Republicans are often accused of having a 'litmus test' on issues like gun control and abortion. But, as Wolfe points out, the Democrats have had one too:

While I agree that the Democrats made a mistake about Robert Casey, I'm skeptical about where Wolfe is going here. Should the Democrats become more receptive to pro-life members? Should it reward the conservative Democrats the way the Republicans have been rewarding high profile liberal/moderate Republicans like Schwarzenegger, Giulani, etc.?

My instinctual answer is, yes, they should. But who and where are they? And: what is the line between flexibility and hypocrisy?

The recent history of American secularization. From the early 1960s to 1994, most liberals have believed in what I call strong secularism, which is both cultural and political. In this strong secularism, religion is supposed to play a small or nonexistent role in public life, while the government is required to uphold strong church-state separation. As Wolfe points out, liberals during this period found their views on religion in cultural life ratified and reinforced by the kinds of decisions the Supreme Court was making on things like prayer in school and (especially) abortion.

What does secularism mean in the era of Promise Keepers and Christian Rock? But strong secularism was dealt a severe blow in 1994, with the Republican revolution. For a number of reasons, liberal democrats are being forced to admit that cultural secularism has become a minority position. But secularism as a legal and judicial concept has remained very much in place. The Republicans have exploited the gap between the two concepts of secularism to great advantage, in part by blurring the line between them. The Democrats' failure to win the God vote perhaps has something to do with their failure to soften strong secularism.

The Democrats' own litmus test. The Democrats have also sometimes made poor decisions on how to respond. For instance, Republicans are often accused of having a 'litmus test' on issues like gun control and abortion. But, as Wolfe points out, the Democrats have had one too:

This secularism achieved the height of its influence within the Democratic Party at its 1996 national convention when Pennsylvania governor Robert Casey was denied a speaking role. There is some dispute about why; many conservatives say it was because his opposition to abortion made him persona non grata within the party, while others point out that he was refused a speaking role because he would not endorse the party's platform. But under either interpretation, the Democratic Party managed to marginalize the Democratic governor of a key swing state because it had made support for abortion a litmus test of party leadership. Believers who might not share the religious right's agenda, but who also worried on religious grounds that the act of abortion really did involve taking away a human life, were told that they ought to look elsewhere for a party to join.

While I agree that the Democrats made a mistake about Robert Casey, I'm skeptical about where Wolfe is going here. Should the Democrats become more receptive to pro-life members? Should it reward the conservative Democrats the way the Republicans have been rewarding high profile liberal/moderate Republicans like Schwarzenegger, Giulani, etc.?

My instinctual answer is, yes, they should. But who and where are they? And: what is the line between flexibility and hypocrisy?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)