The little post I did on Craigslist on Monday evening got me a quick cameo on Radio Open Source (download the MP3 here; I'm at 34:00). Thanks ROS for having me on again, and Craigslist -- do I get a job now?

Incidentally, I had another encounter with radio mini-fame back in June, as a small part of Chris Lydon's interview with Amitav Ghosh.

Postcolonial/Global literature and film, Modernism, African American literature, and the Digital Humanities.

Craigslist as a Metaphor For America

Radio Open Source is doing a bit of an anti-State of the Union address show tomorrow night, to coincide with President Bush's annual meaningless (and utterly skippable) applause-fest. They're calling it Blogs of the Union, or BOTU for short.

As more and more of the country moves online, the most popular websites seem a little like mirrors for society as a whole. Ebay, Craigslist, and, in a sense, Google itself, provide an image of the interests, passions, and problems of millions of people, as we coexist in a seemingly endless array of confined socio-cultural bubbles. Most people just look to their relevant catgories, but it's never been easier to see how the other 300 million live than it is right now.

Of the websites I mentioned, I believe it's Craigslist, with its bewildering main page array of activities, jobs, real estate, stuff for sale, and personals, that makes the best metaphor for America's current state of disunion. On Craigslist, you see it all right in front of you, in its amazing, almost unthinkable diversity. 10 million people a month are using it, for 3 billion page loads. And while it's still a relatively modest minority of Americans who are involved (there are still of course large chunks of society who are not online), it gets a little closer to representativeness every year.

You have dog-clubs and tennis-clubs; sperm donors wanted, and sperm donors offering. You see want ads for potential spouses and some for fiddlers (and some that are both at once). People are looking for Scrabble partners, and people are looking for anonymous sex. There are two million dollar summer homes for sale, along with college kids looking for cheap-as-dirt summer sublets.

And here's my favorite find of the evening, an Indian guy who wants someone to teach him to speak with an American accent, for which he will barter (yes, barter) his skills:

I hope someone takes him up on his offer -- and I think the teacher should be bold enough to request that he offer all five services in the course of a single evening: computer repair, massage, cooked dinner, housecleaning, and good friend/hangout buddy. If there is any cure to allthe world's my important problems (i.e., loneliness, unhealthy food, general aches and pains, and computer woes), it is represented by this remarkable list of offerings.

It's not beside the point that the guy is offering to barter all of these skills to an anonymous stranger. Indeed, nothing could be more 'Craigslisty' than that. While much of what is on tap at the site involves the exchange of money, what's amazing is that so much of Craigslist is driven by people who trust complete strangers with intimate aspects of their lives, on matters that have nothing to do with money whatsoever. If I didn't know better, I would say that it suggests we still have some kind of civil society in place...

But let's not get carried away by our romantic ideals. They don't really apply to Craigslist, where it's all in the particularities -- there's no end to them, and virtually any generalization about them is going to fail.

As more and more of the country moves online, the most popular websites seem a little like mirrors for society as a whole. Ebay, Craigslist, and, in a sense, Google itself, provide an image of the interests, passions, and problems of millions of people, as we coexist in a seemingly endless array of confined socio-cultural bubbles. Most people just look to their relevant catgories, but it's never been easier to see how the other 300 million live than it is right now.

Of the websites I mentioned, I believe it's Craigslist, with its bewildering main page array of activities, jobs, real estate, stuff for sale, and personals, that makes the best metaphor for America's current state of disunion. On Craigslist, you see it all right in front of you, in its amazing, almost unthinkable diversity. 10 million people a month are using it, for 3 billion page loads. And while it's still a relatively modest minority of Americans who are involved (there are still of course large chunks of society who are not online), it gets a little closer to representativeness every year.

You have dog-clubs and tennis-clubs; sperm donors wanted, and sperm donors offering. You see want ads for potential spouses and some for fiddlers (and some that are both at once). People are looking for Scrabble partners, and people are looking for anonymous sex. There are two million dollar summer homes for sale, along with college kids looking for cheap-as-dirt summer sublets.

And here's my favorite find of the evening, an Indian guy who wants someone to teach him to speak with an American accent, for which he will barter (yes, barter) his skills:

I would like to speak English like an American does. I have had my education in British English and brought up in India. As I am working in Philly, I guess my conversation/communication skills is 80% okay with others. But sometimes people find it hard to understand my accent. Would you be interested to teach me the common words, phrases, sentences, lingos, etc ?

I stay near Art museum and any weekday (after 6 PM) is okay with me. Let me know what do you want in return. I don't have any specific thing to offer but here is a list if you are interested:

1. I can fix your computer, software, hardware problem (including Laptop)

2. Give you a Massage (I am a certified therapist for head massage)

3. Prepare food, specially nice indian curries etc

4. May be help you to clean the house or some other work

5. May be a good friend, hangout buddy

I hope someone takes him up on his offer -- and I think the teacher should be bold enough to request that he offer all five services in the course of a single evening: computer repair, massage, cooked dinner, housecleaning, and good friend/hangout buddy. If there is any cure to all

It's not beside the point that the guy is offering to barter all of these skills to an anonymous stranger. Indeed, nothing could be more 'Craigslisty' than that. While much of what is on tap at the site involves the exchange of money, what's amazing is that so much of Craigslist is driven by people who trust complete strangers with intimate aspects of their lives, on matters that have nothing to do with money whatsoever. If I didn't know better, I would say that it suggests we still have some kind of civil society in place...

But let's not get carried away by our romantic ideals. They don't really apply to Craigslist, where it's all in the particularities -- there's no end to them, and virtually any generalization about them is going to fail.

Movies Seen Recently, Music I'm Listening To

We did go out and see Capote and Brokeback Mountain over the past few weeks, and while I wasn't enthralled by either film, I prefer Capote over Brokeback. I enjoyed Ang Lee's film -- I thought it was elegant and spare -- but also on the verge of sweepy and hollow. Maybe I remained generally unmoved by the film because it is an image of an era ('the closet') that has passed? Or perhaps because it's simply a romance that never quite gets to full boil. Whatever the case, I thought Brokeback Mountain managed to be impressive without being particularly moving or inspiring.

(The one image that has stayed in my mind is the brief moment of violence that appears at the end of the film, involving Jake Gyllenhal's character... you know the scene I'm thinking of... terrifying)

Capote at least gets into the murky waters of the writer's (inevitable?) exploitation of his subject. I tend to side against Truman Capote: I would rather be a bad writer and a good person, than a good writer who denatures (or destroys) his subject to get the Story. There is a lot to debate here: was Capote really all that great? And: can't he be accused of helping to start the era of the mass-media's sensationalizing of violent crime? Or maybe: he was a great writer and a terrible human being? Or: aren't all great writers pretty much that way?

* * *

And here are some older films I've been watching over the past few weeks:

Side Streets (1998; IMDB). Shashi Kapoor plays a really strange role in this small art movie about working-class ethnic New York. Kapoor plays a huge (in more than one sense) movie star whose brother is an NYC taxi driver married to Shabana Azmi. That alone seems rather unrealistic -- one finds it hard to accept that a huge Bollywood star might have a siblings who drive taxis in New York -- but the rest of the film is gritty and believable. There are also parallel plots involving Russian drug dealers, abject fashion designers, and an Afro-Caribbean couple who bicker at length about permission to drive a car. But the real reason to see the film is the scene at the end, where Shashi Kapoor goes nuts and pulls a Charles Bukowski in a posh hotel room.

Ash Wednesday (2002; IMDB). Another New York indie film, this one directed by Edward "cheekbones" Burns of The Brothers McMullen. Ed Burns is a little like John Cassavetes back in the day -- a commercial actor who makes low-budget independent films with the cash he gets from the forgettable films he does in Hollywood. And while Burns's films lack the searing emotional upheaval of Cassavetes flicks like Opening Night or Faces, there is something interesting going on here. The plot of Ash Wednesday is pretty gripping, though the acting by the Irish gangsters of Hell's Kitchen is at times quite weak. The Catholic themes of sacrifice, rebirth, and redemption are strangely appropriate for a gangster film, and are all at play in the film's climactic scenes.

Mr. Smith Goes To Washington (1939; IMDB). There is nothing to criticize in this film: snappy 1930s dialogue, great plot, and total relevance to politics today (you can substitute Jack Abramoff for the bad guy in the film without any difficulty whatsoever). It also has the distinction of being the only world-class film I've ever seen that portrays a Senate filibuster as a scene of climactic, world-changing action.

Fiddler on the Roof (1971; IMDB). Yeah, I know it's a banal Broadway myth of the Russian Jewish shtetl, but the songs in this movie are just too much fun. And Topol's big lines have great camp value; I'm especially keen on the moments where he shouts "Tradition!" in an accusing way at God, only to wave off after a moment (eh, ok, so much for tradition). I only hope I'm half this entertaining and melodramatic when I'm fifty. Watching this again also reignited my interest in the Yiddish writer Sholom Aleichem, whose works I'm somewhat curious to read.

The First Time (1969; IMDB). This movie was made in 1969, but it feels like 1954. Wow, is it dated -- it has a script that seems to have been written by a rather sleazy fifteen year old boy. Just truly awful dialogue; I don't know how I watched it all the way through. Maybe it had something to do with Jacqueline Bisset? That would probably be a good guess.

Home Delivery (2005). We watched about half of this recent Bollywood film before falling asleep. It felt like a collage of bits from a TV sitcom crudely stitched together to try and form a film. Yawn -- and that, needless to say, pretty much sums up my attitude to most Bollywood flicks that have been coming out lately (except perhaps Bluffmaster and 15 Park Avenue, both of which I want to see).

* * * * *

I've been listening to Matisyahu's Live at Stubb's, The Decemberists' Castaways and Cutouts and Picareseque, and the Bluffmaster CD soundtrack. Both the Decemberists and Bluffmaster rock, though in very different ways.

I'm still trying to decide about Matisyahu, who takes an Orthodox/Hasidic messianic vision and channels it into the lyrical and melodic conventions of roots rock reggae and dub. At times it feels a little like a gimmick, but some of the songs really do click quite nicely. There is some real poetry here, though there is also, on some of the longer "jams," a little smelly Phish. We'll see what they do with the studio album...

The Decemberists have been doing their thing for a few years, but I only just got their new CD a month ago. These are, I think, the best-written lyrics I've come across in recent years. Magnificent -- deserving of a separate post (coming soon, hopefully).

And on the lighter side of things, Bluffmaster is the ultimate Bollywood/Hip Hop fusion, complete with spadefuls of swagger. And with cool baritone vocals on some of the best tracks, Abhishek Bachchan is coming to fill in his father's shoes more and more... I don't know if "Sabse Bada Rupaiyya" is going to be as immortal as "Rang Barse," but at least it's got a nice beat and you can dance to it.

(The one image that has stayed in my mind is the brief moment of violence that appears at the end of the film, involving Jake Gyllenhal's character... you know the scene I'm thinking of... terrifying)

Capote at least gets into the murky waters of the writer's (inevitable?) exploitation of his subject. I tend to side against Truman Capote: I would rather be a bad writer and a good person, than a good writer who denatures (or destroys) his subject to get the Story. There is a lot to debate here: was Capote really all that great? And: can't he be accused of helping to start the era of the mass-media's sensationalizing of violent crime? Or maybe: he was a great writer and a terrible human being? Or: aren't all great writers pretty much that way?

* * *

And here are some older films I've been watching over the past few weeks:

Side Streets (1998; IMDB). Shashi Kapoor plays a really strange role in this small art movie about working-class ethnic New York. Kapoor plays a huge (in more than one sense) movie star whose brother is an NYC taxi driver married to Shabana Azmi. That alone seems rather unrealistic -- one finds it hard to accept that a huge Bollywood star might have a siblings who drive taxis in New York -- but the rest of the film is gritty and believable. There are also parallel plots involving Russian drug dealers, abject fashion designers, and an Afro-Caribbean couple who bicker at length about permission to drive a car. But the real reason to see the film is the scene at the end, where Shashi Kapoor goes nuts and pulls a Charles Bukowski in a posh hotel room.

Ash Wednesday (2002; IMDB). Another New York indie film, this one directed by Edward "cheekbones" Burns of The Brothers McMullen. Ed Burns is a little like John Cassavetes back in the day -- a commercial actor who makes low-budget independent films with the cash he gets from the forgettable films he does in Hollywood. And while Burns's films lack the searing emotional upheaval of Cassavetes flicks like Opening Night or Faces, there is something interesting going on here. The plot of Ash Wednesday is pretty gripping, though the acting by the Irish gangsters of Hell's Kitchen is at times quite weak. The Catholic themes of sacrifice, rebirth, and redemption are strangely appropriate for a gangster film, and are all at play in the film's climactic scenes.

Mr. Smith Goes To Washington (1939; IMDB). There is nothing to criticize in this film: snappy 1930s dialogue, great plot, and total relevance to politics today (you can substitute Jack Abramoff for the bad guy in the film without any difficulty whatsoever). It also has the distinction of being the only world-class film I've ever seen that portrays a Senate filibuster as a scene of climactic, world-changing action.

Fiddler on the Roof (1971; IMDB). Yeah, I know it's a banal Broadway myth of the Russian Jewish shtetl, but the songs in this movie are just too much fun. And Topol's big lines have great camp value; I'm especially keen on the moments where he shouts "Tradition!" in an accusing way at God, only to wave off after a moment (eh, ok, so much for tradition). I only hope I'm half this entertaining and melodramatic when I'm fifty. Watching this again also reignited my interest in the Yiddish writer Sholom Aleichem, whose works I'm somewhat curious to read.

The First Time (1969; IMDB). This movie was made in 1969, but it feels like 1954. Wow, is it dated -- it has a script that seems to have been written by a rather sleazy fifteen year old boy. Just truly awful dialogue; I don't know how I watched it all the way through. Maybe it had something to do with Jacqueline Bisset? That would probably be a good guess.

Home Delivery (2005). We watched about half of this recent Bollywood film before falling asleep. It felt like a collage of bits from a TV sitcom crudely stitched together to try and form a film. Yawn -- and that, needless to say, pretty much sums up my attitude to most Bollywood flicks that have been coming out lately (except perhaps Bluffmaster and 15 Park Avenue, both of which I want to see).

* * * * *

I've been listening to Matisyahu's Live at Stubb's, The Decemberists' Castaways and Cutouts and Picareseque, and the Bluffmaster CD soundtrack. Both the Decemberists and Bluffmaster rock, though in very different ways.

I'm still trying to decide about Matisyahu, who takes an Orthodox/Hasidic messianic vision and channels it into the lyrical and melodic conventions of roots rock reggae and dub. At times it feels a little like a gimmick, but some of the songs really do click quite nicely. There is some real poetry here, though there is also, on some of the longer "jams," a little smelly Phish. We'll see what they do with the studio album...

The Decemberists have been doing their thing for a few years, but I only just got their new CD a month ago. These are, I think, the best-written lyrics I've come across in recent years. Magnificent -- deserving of a separate post (coming soon, hopefully).

And on the lighter side of things, Bluffmaster is the ultimate Bollywood/Hip Hop fusion, complete with spadefuls of swagger. And with cool baritone vocals on some of the best tracks, Abhishek Bachchan is coming to fill in his father's shoes more and more... I don't know if "Sabse Bada Rupaiyya" is going to be as immortal as "Rang Barse," but at least it's got a nice beat and you can dance to it.

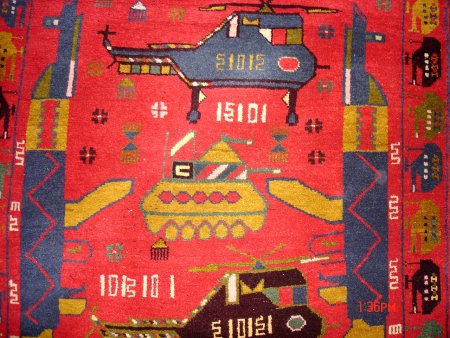

Hindutva In American Schools: Links

Some excellent posts by bloggers on the recent controversy in California over attempts by Hindu groups to have their version of Indian history incorporated into school textbooks (see the Christian Science Monitor). While the California school board initially approved changes earmarked for them by the Vedic Foundation and the Hindu Education Foundation, after a concerted effort by academics the changes have been reversed. See, academic expertise does matter for something.

--The great science-blogger Pharyngula, now from his new site:

(As far as I'm concerned, the fundamentalist Christian ideas are equally strange, but that's a small quibble!)

--Butterflies and Wheels, an equally steadfast advocate of secularist thinking.

--Our new blog-friend, the Accidental Blogger

--And here's Archana.

Suffice it to say, I find the prospect of the incursion of Hindutva ideology into the American school system pretty surreal.

UPDATE: This is just a links post. See my more detailed response to the California controversy here.

--The great science-blogger Pharyngula, now from his new site:

Yeah, these aren't fundamentalist Christians, but Hindu nationalists with very strange ideas—still, it's the same old religious nonsense.

(As far as I'm concerned, the fundamentalist Christian ideas are equally strange, but that's a small quibble!)

--Butterflies and Wheels, an equally steadfast advocate of secularist thinking.

--Our new blog-friend, the Accidental Blogger

--And here's Archana.

Suffice it to say, I find the prospect of the incursion of Hindutva ideology into the American school system pretty surreal.

UPDATE: This is just a links post. See my more detailed response to the California controversy here.

Tyeb Mehta -- overhyped? (try Prosenjit Roy)

I posted on Tyeb Mehta a few months ago, after it came out that a painting of his had sold for $1.58 million at Christie's in New York.

Somini Sengupta has a thorough profile of Mehta in the Times this week, which is pretty well worth reading for the insight it gives on what Mehta is after with his myth-based gestural paintings. (Also helpful is Sonia Faleiro's nice profile of him, which appeared in Tehelka in June.)

And I came across a recent first-person testimonial by Mehta in the Times of India, where he talks about his active (if non-devout) relationship to his Shia Islamic heritage.

I know much more about Mehta after reading these pieces -- and he seems like a fascinating person -- but I'm still on the fence as to whether I actually like his paintings or not. The images just seem somehow flat to me (have a look at the Times' slideshow and tell me what you think...)

While the shapes Mehta produces are dramatic, they seem more like drawings than paintings: they are flat and descriptive even when the images involve violence, suffering, or mutilation. (Sengupta mentions the traumatic effect of communal violence on Mehta's thinking...) The monstrous, misshapen bodies in his paintings ought to provoke visceral horror, but that's not what happens for this blogger at least.

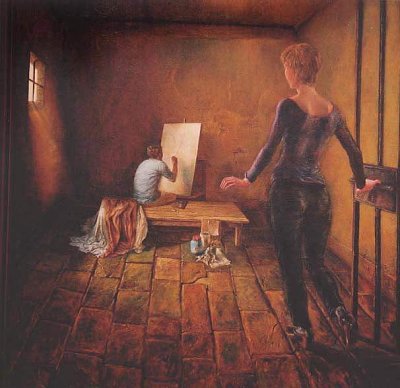

Contrast his work to that of another contemporary painter, Prosenjit Roy. Roy has some paintings on Jalsaghar, and more on his own homepage. Alongside whimsical paintings like "The Sleepy Scratch" is the more serious "Artist on a mend," a painting about depression which, I would argue, has a painterly joke in it all the same:

(Do you get the joke? Hint: It's on you.)

But Roy's most ambitious painting might be The Order of Things, which he hasn't posted in full color -- perhaps to protect it from Internet leechers (**blogger coughs nervously**). It looks like a surrealist take on the philosophical arguments of Michel Foucault...

Somini Sengupta has a thorough profile of Mehta in the Times this week, which is pretty well worth reading for the insight it gives on what Mehta is after with his myth-based gestural paintings. (Also helpful is Sonia Faleiro's nice profile of him, which appeared in Tehelka in June.)

And I came across a recent first-person testimonial by Mehta in the Times of India, where he talks about his active (if non-devout) relationship to his Shia Islamic heritage.

I know much more about Mehta after reading these pieces -- and he seems like a fascinating person -- but I'm still on the fence as to whether I actually like his paintings or not. The images just seem somehow flat to me (have a look at the Times' slideshow and tell me what you think...)

While the shapes Mehta produces are dramatic, they seem more like drawings than paintings: they are flat and descriptive even when the images involve violence, suffering, or mutilation. (Sengupta mentions the traumatic effect of communal violence on Mehta's thinking...) The monstrous, misshapen bodies in his paintings ought to provoke visceral horror, but that's not what happens for this blogger at least.

Contrast his work to that of another contemporary painter, Prosenjit Roy. Roy has some paintings on Jalsaghar, and more on his own homepage. Alongside whimsical paintings like "The Sleepy Scratch" is the more serious "Artist on a mend," a painting about depression which, I would argue, has a painterly joke in it all the same:

(Do you get the joke? Hint: It's on you.)

But Roy's most ambitious painting might be The Order of Things, which he hasn't posted in full color -- perhaps to protect it from Internet leechers (**blogger coughs nervously**). It looks like a surrealist take on the philosophical arguments of Michel Foucault...

Bengaluru

There is a great -- really great -- piece by Ruchir Joshi on India's addiction to renaming in the Calcutta Telegraph. As many readers will be aware by now, Bangalore will be changing its name to Bengaluru.

Hm, I think I know the word he's thinking of in Hindi, though not Bangla.

Along the way, Joshi makes some great points about how place-names function in India, across a wide spectrum of languages:

(First thought: "Sex Pyaar"? Too good.)

Second thought: Yes, exactly, exactly. And there are other good points; go read the whole thing.

Incidentally, if you haven't already, you should check out Sepia Mutiny's parody of the name change here, though commenter Raghu offers a defense of "Bengaluru" that is also worth considering as a counter-point:

Something about the name brought out the schoolboy in all three of us and the holiday was rife with jokes. Was the name-change proposed by a local Bong? If not, why on earth would IT-rich, culturally proud, ’Digas [Kannadigas] want ‘Bengal’ included in the name of their capital city? The second half, ‘luru’, with a couple of letters added or changed, led to all sorts of dormitory-humour, wisecracks unreproducable in a family newspaper such as this, except it suffices to say that the tweaked ‘luru’ could play one way in the Hindi we all spoke, and another in the Bangla with which we were all familiar.

On the flight back, a slightly more serious vein of thought asserted itself. I remember clearly how angry I became when Bombay was officially renamed Mumbai a decade ago, and again, when the same thing happened soon after to Madras and then, finally, to Calcutta. Usually this anger remains contained to a note I add when writing for newspapers and magazines unfamiliar with my preferences, a note which requests everyone to kindly leave alone the city names I use, such as Calcutta, Bombay or Madras. But now, with the imminent adding of Bangalore to this list, the whole issue rekindles itself for me and it’s about far more than just names.

Hm, I think I know the word he's thinking of in Hindi, though not Bangla.

Along the way, Joshi makes some great points about how place-names function in India, across a wide spectrum of languages:

While I am all for changing ‘Road’, ‘Street’ and ‘Avenue’ to Sarani, Marg and Vithi, happy with the exchange of Lansdowne for Sarat Bose and chortlingly happy with the kicking out of Harrington in favour of Ho Chi Minh and the cancelling of Camac to install Shakespeare, (or even ‘Sex Pyaar’ as one signboard notably proclaimed), to my mind the same principle does not apply to city names.

This is because, a city, like a country, is a much larger, a much more complex construct than a lane or a plaza. There is a reason why most people reading this column probably did not pause to think twice about my use of 'India' and 'Indian' in the previous paragraph but one: 'India', much more than 'Hindustan', 'Bharat', or 'Bharatam', is the name that is now truly representative of the country we live in; it is the one agreed name that diverse people from all over the country use regularly and without quarrel, and, since the spread of cricket and television, it is a name that is now freely used across city, small town and even village; also, not unimportantly, now that we see ourselves as deeply connected to the world, it is the name by which the international community knows us and recognizes us.

Similarly, what a ‘Calcutta’ or a ‘Bombay’ signifies is a typically subtle Indian way of eating your cake and having it too. What the old names say, which Mumbai and Kolkata don’t, is: ‘yes, we come from a colonial history, but also, yes, we have overcome that colonial past and are confident enough to keep whatever is useful from that past, whether it be the English language, our railway network, or, indeed, the names of two of our most famous cities. Just as the name India provides a nomenclatural umbrella to awesome diversity, so do the names of these urban leviathans provide each a name-shelter under which all who have contributed to that living city can live and continue to work.’

(First thought: "Sex Pyaar"? Too good.)

Second thought: Yes, exactly, exactly. And there are other good points; go read the whole thing.

Incidentally, if you haven't already, you should check out Sepia Mutiny's parody of the name change here, though commenter Raghu offers a defense of "Bengaluru" that is also worth considering as a counter-point:

Those of us who are objecting probably also need to examine why we're so distressed about the change. After all, law does not change names, it just changes spelling. Theres a sentiment that stirs beneath our rational, political arguments about the adequacy of the status quo and the dangers of linguistic nationalism and tubthumping - its our anxiety at the fact that our precarious culture, not fully Western but certainly not fully Kannadiga, just got pushed onto its back foot. Taking the names entirely on their own accoustic merits, Bengaluru is so soft and mellifluous, but Bangalore shakes off those drooping vowels and is crisper, more anglicized - it sounds like the city we want it to become for our comfort - and that's our linguistic chauvinism.

"Abandoning the Duty of the Painted Bench" (Pamuk charges dropped)

Reuters reports that charges against Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk have been dropped. He was originally accused of insulting "Turkishness" when he referred to the genocide of the Armenians in the 1910s, in an interview with a European reporter.

Under Turkey's Article 301, many writers have been charged and imprisoned over the years for criticizing the government, Turkishness, or the memory of Kemal Ataturk (though there is actually a separate law for that). And besides Pamuk, there are a number of active cases that should still concern us. Amnesty has a long list:

Over at Verbal Privilege, Elizabeth echoes Amnesty, in worrying about all of the active cases, not just Pamuk's:

Under Turkey's Article 301, many writers have been charged and imprisoned over the years for criticizing the government, Turkishness, or the memory of Kemal Ataturk (though there is actually a separate law for that). And besides Pamuk, there are a number of active cases that should still concern us. Amnesty has a long list:

Hrant Dink is a journalist and the editor of the Armenian-language weekly newspaper Agos, which is published in Istanbul. On 7 October 2005, Hrant Dink was given a six-month suspended prison sentence by the Sisli Court of First Instance No. 2 in Istanbul for “denigrating Turkishness” in an article he wrote on Armenian identity. According to the prosecutor in the case, Hrant Dink had written his article with the intention of denigrating Turkish national identity.

Sehmus Ulek is the Vice-President of the Turkish human rights NGO Mazlum Der. On 28 April 2005 the Sanlıurfa Court of First Instance No. 3 started hearing a case against him and Hrant Dink, under Article 159 of the old TPC (now Article 301) for speeches they made during a conference organized by Mazlum Der’s Urfa branch on 14 December 2002 entitled “Global Security, Terror and Human Rights, Multi-culturalism, Minorities and Human Rights”. Sehmus Ulek referred in his speech to the nation-building project of the Turkish Republic as it had affected, in particular, the southeastern area of the country; Hrant Dink discussed his own relationship to official conceptions of Turkish identity. The next hearing of the case will take place on 9 February 2006.

A trial began in May 2005 at the Beyoglu Court of First Instance No. 2 in Istanbul against publisher Ragip Zarakolu for his publication of a Turkish translation of a book by Dora Sakayan entitled Experiences of an Armenian Doctor: Garabet Hacheryan's Izmir Journal (Bir Ermeni Doktorun Yasadıkları: Garabet Haceryan'ın İzmir Guncesi; Istanbul: Belge 2005). Ragip Zarakolu had been charged under Article 159 of the TPC for “denigrating Turkishness and the security forces”, and then under Article 301 after the new TPC came into effect.

Fatih Tas is a 26-year-old student of Communications and Journalism at Istanbul University and the owner of Aram publishing house. He is currently being tried under Article 301 because he published a Turkish translation of a book by the American academic John Tirman, entitled Savas Ganimetleri: Amerikan Silah Ticaretinin Insan Bedeli (Istanbul: Aram, 2005) (The Spoils of War: the Human Cost of America’s Arms Trade), that reportedly includes a map depicting a large section of Turkey as traditionally Kurdish and alleges that the Turkish military perpetrated a number of human rights abuses in the south-east of the country during the 1980s and 1990s.

Murat Pabuc was a lieutenant in the Turkish army who retired on grounds of disability. Whilst still serving, he witnessed the massive earthquake that hit Turkey in August 1999, as well as the institutional corruption that he alleges followed it. He became disillusioned with his military duties, seeing soldiers as being alienated from ordinary people, and began to refuse orders. He eventually began undergoing psychiatric treatment. In June 2005 he published his book Boyalı Bank Nobetini Terk Etmek; the literal translation of this title is "Abandoning the Duty of the Painted Bench." It alludes to a Turkish anecdote which portrays a pastiche of a soldier following orders unquestioningly. He believes that this was the only way for him to express what he had experienced in the army. As a result he is facing a trial for “public denigration of the military” under Article 301.

Birol Duru is a journalist. On 17 November 2005 he was charged with "denigrating the security forces" under Article 301 because he published on the Dicle news agency a press release from the Human Rights Association (IHD) Bingol branch which stated that the security forces were burning forests in Bingol and Tunceli. The president of IHD’s Bingol branch, Rıdvan Kızgın, is also charged under other legislation for the contents of the press release. Rıdvan Kızgın has had over 47 cases opened against him since 2001, and Amnesty International is currently running a web action

for him as part of its ongoing campaigning work on human rights defenders in Turkey and Eurasia. Birol Duru is due to be sentenced on 8 December 2005.(link)

Over at Verbal Privilege, Elizabeth echoes Amnesty, in worrying about all of the active cases, not just Pamuk's:

That said, I'm still worried about the many ongoing cases against other writers, journalists, publishers, and activists that do not receive a fraction of the attention Pamuk's case got. The cases of people like Hrant Dink, Ragip Zarakolu, and Ferhat Tunç are a more crucial barometer of freedom of expression in Turkey--we'll see what happens to persectued writers and artists who do not enjoy the benefit of an international outcry.

Buffalo DNA: Two New Bloggers

I want to welcome Amitava Kumar to blogistan. Amitava is one of the sharpest and most opinionated Indian cultural critics around, and I have no doubt he'll be a very formidable blogger.

A good start is his recent slam of a billboard advertisement used by the newspaper Daily News and Analysis:

Go to his blog to see the picture in question. Incidentally, the post also attacks the content of the paper in question, singling out a very bad recent book review of a novel also related to Bihar, Siddharth Chowdhury's Patna Roughcut.

Wow, inspired ranting. My timid gloss on this might be something like: Amitava doesn't like the ad because it takes a very smug potshot at political corruption in Bihar. Even granted that corruption and government waste might well be a problem, it isn't going to be solved by cheap shots from the snide, metropolitan, soi-disant cognoscenti.

* * *

While I'm promoting new blogs, let me encourage people to take a peek at Ruchira Paul's Accidental Blogger. Ruchira is a strong champion for liberal politics, both in the U.S. and in India. A recent post on "Anthropomorphism and Empathy" stood out to me, as did this brief post on the female foeticide problem I was talking about earlier this week.

She's also done interesting some literature-oriented posts. (Do more lit posts, Ruchira!)

A good start is his recent slam of a billboard advertisement used by the newspaper Daily News and Analysis:

Will someone suggest a caption for this photograph? I saw this billboard near a highway in Bombay and understood that it was an ad for a newspaper called DNA. I would describe it as the pavement-level version of a Rushdie novel–self-satisfied metropolitan fiction for consumption by the metropolitans. It is not the buffalo who has decided to carry a reminder on its body that it must work for Bihar; instead, it is some clueless cosmopolitan who is announcing his never-to-be-really-actualized intentions about–what exactly?–social activism. If this individual has recovered from his new year’s hangover by now I’d like him to consider why the geography of a land and its peoples is reducible to a buffalo’s hide. Perhaps I am over-reacting but this is because the rag in question has dung in its DNA.

Go to his blog to see the picture in question. Incidentally, the post also attacks the content of the paper in question, singling out a very bad recent book review of a novel also related to Bihar, Siddharth Chowdhury's Patna Roughcut.

Wow, inspired ranting. My timid gloss on this might be something like: Amitava doesn't like the ad because it takes a very smug potshot at political corruption in Bihar. Even granted that corruption and government waste might well be a problem, it isn't going to be solved by cheap shots from the snide, metropolitan, soi-disant cognoscenti.

* * *

While I'm promoting new blogs, let me encourage people to take a peek at Ruchira Paul's Accidental Blogger. Ruchira is a strong champion for liberal politics, both in the U.S. and in India. A recent post on "Anthropomorphism and Empathy" stood out to me, as did this brief post on the female foeticide problem I was talking about earlier this week.

She's also done interesting some literature-oriented posts. (Do more lit posts, Ruchira!)

'Hindu Protestantism': Nirad Chaudhuri on Hindu Reformers

I'm teaching a short excerpt of Nirad Chaudhuri's Autobiography of an Unknown Indian (1951). It's about 30 pages in Amitava Kumar's Away: The Indian Writer as an Expatriate, mainly concerning Chaudhuri's early understandings of England, the English language, and Englishness as a child in Bengal.

One part that caught my eye is his characterization of the Hindu reform movements, which would include the Brahmo Samaj as well as what he calls the 'orthodox counterblast' (I believe Chaudhuri's own family tended towards the latter). In truth, the two movements were not so far apart from one another, and many members of the latter community began as dissenting Brahmo Samaj members.

Here is Chaudhuri (hope you enjoy the long quote):

This is interesting in lots of ways, one of which being of course the question it raises about where Nirad Chaudhuri sees himself (as I mentioned, I believe Chaudhuri's own parents would have counted themselves among the reformers he's criticizing above).

The other major point I draw out ot this is a reminder to anyone who advocates strong forms of cultural or religious purity, that everything is always already mixed, contaminated, and hybridized. That hybridity is particularly intense in the Indian context for historical reasons: both the Brahmo Samaj and the "orthodox counterblast" are heavily dependent on ideas derived from the Protestant missionaries in their midst. Their sectarian disputes, one could even say, mimicked the sectarian disputes between Protestant sects (Unitarians, Methodists, etc.).

Needless to say, the caution about false purity could well be applied to all religious communities.

One part that caught my eye is his characterization of the Hindu reform movements, which would include the Brahmo Samaj as well as what he calls the 'orthodox counterblast' (I believe Chaudhuri's own family tended towards the latter). In truth, the two movements were not so far apart from one another, and many members of the latter community began as dissenting Brahmo Samaj members.

Here is Chaudhuri (hope you enjoy the long quote):

My father and mother believed in a form of Hinduism whose basis was furnished by a special interpretation of the Hindu religion. According to this interpretation the history of Hinduism could be divided into three stages: a first age of pure faith, in essence monotheistic, with its foundations in the Vedas and the Upanishads; secondly, a phase of eclipse during the predominance of Buddhism; and thirdly, the later phase of gross and corrupt polytheism. The adherents of this school further held that all the grosser polytheistic accretions with which popular Hindusim was disfigured had crept in at the time of the revial of Hinduism after the decline of Buddhism in the seventh and eighth centuries of the Christian era, and that they were due primarily to the influence of Mahayana or polytheistic northern Buddhism and Tantric cults. This degnerate form of Hinduism was given the name of Puranic Hinduism in order to distinguish it from the ealier and purer Upanishadic form of Hinuism. The reformers claimed that they were trying only to restore the original purity of the Hindu religion.

The very simplicity of the interpretation should serve to put historical students on their guard against it. But the reformers implicitly believed in it, and since they believed in, their belief gave shape to and coloured their attitude to the other religious movements of the world; they failed to detect the true filiation of their theory, to see that that was only an echo and duplication of the theory of the Protestant Reformation. Although their claim to be restoring the pure faith of the Upanishads by ridding it of Puranic excrescences was certainly inspired by an unconscious absorption of the idea of the Protestants that they were reviving the pure faith of the Scriptures, the Apostles, and the early Fathers, the Hindu reformers looked upon Protestantism as the product of a parallel religious movement and were deeply sympathetic to it.

This is interesting in lots of ways, one of which being of course the question it raises about where Nirad Chaudhuri sees himself (as I mentioned, I believe Chaudhuri's own parents would have counted themselves among the reformers he's criticizing above).

The other major point I draw out ot this is a reminder to anyone who advocates strong forms of cultural or religious purity, that everything is always already mixed, contaminated, and hybridized. That hybridity is particularly intense in the Indian context for historical reasons: both the Brahmo Samaj and the "orthodox counterblast" are heavily dependent on ideas derived from the Protestant missionaries in their midst. Their sectarian disputes, one could even say, mimicked the sectarian disputes between Protestant sects (Unitarians, Methodists, etc.).

Needless to say, the caution about false purity could well be applied to all religious communities.

Claim: Female Foeticide Correlates with Wealth, Education

Via Quizman, an article in the Christian Science Monitor about India's female foeticide problem (also discussed by Uma, Neha Viswanathan, and Abhi, among many others).

Here is the CSM:

I don't see hard and fast evidence in this statement or elsewhere CSM article for the claim, but several sources in the article suggest a correlation between wealth and education, and higher incidences of female foeticide. It makes some sense: wealthier families can afford the multiple ultrasounds and the abortion procedure. And the strongest evidence for the claim comes from the fact that birth ratios tend to be the most skewed in relatively prosperous agricultural states like Haryana and Punjab.

It doesn't account for everything, of course -- boy/girl birth ratios in relatively prosperous states in South India are at or near normal levels (according to this map based on recent census information). So there definitely are some cultural factors at work, but it's not as simple as "Punjabis are more patriarchal."

Incidentally, the Indian Medical Association, though it has condemned female foeticide, is questioning Lancet's claim that 10,000,000 female foetuses have been aborted via sex-selection in the past 20 years, of which 5 million abortions are said to have taken place after the procedure was banned in 1994.

According to the BBC article, the IMA claims that since 2001 a crackdown on ultrasound equipment has led to a dramatic drop in female foeticide. But it will be another five years (the next census) before we have any reliable data on that, so there's almost no point in even discussing it at present. (Or not: are there other sources for sex-ratio statistics that might be used to sort this out?)

Here is the CSM:

The practice is common among all religious groups - Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Muslims, and Christians - but appears to be most common among educated women, a fact that befuddles public health officials and women's rights activists alike.

"More educated women have more access to technology, they are more privileged, and most educated families have the least number of children," says Sabu George, a researcher with the Center for Women's Development Studies in New Delhi, who did not participate in the study. "This is not just India. Everywhere in the world, smaller families come at the expense of girls."

I don't see hard and fast evidence in this statement or elsewhere CSM article for the claim, but several sources in the article suggest a correlation between wealth and education, and higher incidences of female foeticide. It makes some sense: wealthier families can afford the multiple ultrasounds and the abortion procedure. And the strongest evidence for the claim comes from the fact that birth ratios tend to be the most skewed in relatively prosperous agricultural states like Haryana and Punjab.

It doesn't account for everything, of course -- boy/girl birth ratios in relatively prosperous states in South India are at or near normal levels (according to this map based on recent census information). So there definitely are some cultural factors at work, but it's not as simple as "Punjabis are more patriarchal."

Incidentally, the Indian Medical Association, though it has condemned female foeticide, is questioning Lancet's claim that 10,000,000 female foetuses have been aborted via sex-selection in the past 20 years, of which 5 million abortions are said to have taken place after the procedure was banned in 1994.

According to the BBC article, the IMA claims that since 2001 a crackdown on ultrasound equipment has led to a dramatic drop in female foeticide. But it will be another five years (the next census) before we have any reliable data on that, so there's almost no point in even discussing it at present. (Or not: are there other sources for sex-ratio statistics that might be used to sort this out?)

Desi Lit Links from the Literary Saloon; and a Short Rant Critique of Arundhati Roy

Literary Saloon has a number of posts relating to Indian literature up right now:

--Another James Laine book on Sivaji has been banned in Maharashtra. Apparently the offense this time is Laine's claim that Chhatrapati Sivaji was an "Oedipal rebel," which basically means he fought with his father. A pretty laughable reason to ban it, but then, there are never good reasons to ban books. (Stop the Maharashtra government before they ban again!)

--Neha Sharma has something in Asian Age, on the status of Hindi literature. Unfortunately, the link is already dead (though Lit Saloon has a couple of paragraphs quoted).

--The same Lit Saloon post also links to this story about Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's presiding over the re-release of two books by Premchand. Interesting to hear the PM's thoughts on some works of literature...

--And Arundhati Roy has turned down a Sahitya Akademi award for best writing in English, for The Algebra of Infinite Justice.

Whoa. A shrill -- and dated -- tirade is the best piece of writing to have come out in English by an Indian citizen last year? And didn't she publish that essay four and a half years ago (and the accompanying book three years ago)? That she's turning them down serves them right; they could do a lot better.

I'm critical of the Indian and American governments for many things, but I'm so over Arundhati Roy. (Read the original essay from September 2001 at the Guardian.) Over the course of the essay, Roy says many things that are true, and that I agree with -- she certainly sees clearly where George W. Bush is going with "Operation Enduring Freedom," and presciently predicts the failure of a "war on terror" that, since the invasion of Iraq, has gone completely astray.

But Roy also makes some very paranoid generalizations in that essay, which I believe are unsupportable. Here is one of the worst:

She might have a point that the wrong of 9/11 is no worse than, for instance, the wrongs the U.S. has at times committed in the name of freedom or justice, or which have followed indirectly from its actions (as in, 100,000 dead Iraqi civilians since the beginning of the most recent war -- a war which didn't need to happen in the first place).

But I don't see the point in claiming that the two types of violence are "interchangeable," or that Osama Bin Laden is America's "family secret" and also its "doppleganger." No, he's not: they are separate evils, and merging them is sloppy thinking. And I don't see the point in bringing in multinational corporations -- their function is quite different from that of the U.S. military, even if some function as auxiliaries for military projects. But McDonald's and Microsoft are not the same as Halliburton, and the mere fact that all three have well-paid corporate executives does not make make them all evil.

I'm not that far from Roy on some issues of substance (at least in this particular essay; I do think many of her positions on other issues are absurd [see her comments last year on cell-phones in India, for instance]). But I'd rather describe things plainly, as they are, and without the breathless ramification of rhetoric that she seems to relish so much.

--Another James Laine book on Sivaji has been banned in Maharashtra. Apparently the offense this time is Laine's claim that Chhatrapati Sivaji was an "Oedipal rebel," which basically means he fought with his father. A pretty laughable reason to ban it, but then, there are never good reasons to ban books. (Stop the Maharashtra government before they ban again!)

--Neha Sharma has something in Asian Age, on the status of Hindi literature. Unfortunately, the link is already dead (though Lit Saloon has a couple of paragraphs quoted).

--The same Lit Saloon post also links to this story about Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's presiding over the re-release of two books by Premchand. Interesting to hear the PM's thoughts on some works of literature...

--And Arundhati Roy has turned down a Sahitya Akademi award for best writing in English, for The Algebra of Infinite Justice.

Whoa. A shrill -- and dated -- tirade is the best piece of writing to have come out in English by an Indian citizen last year? And didn't she publish that essay four and a half years ago (and the accompanying book three years ago)? That she's turning them down serves them right; they could do a lot better.

I'm critical of the Indian and American governments for many things, but I'm so over Arundhati Roy. (Read the original essay from September 2001 at the Guardian.) Over the course of the essay, Roy says many things that are true, and that I agree with -- she certainly sees clearly where George W. Bush is going with "Operation Enduring Freedom," and presciently predicts the failure of a "war on terror" that, since the invasion of Iraq, has gone completely astray.

But Roy also makes some very paranoid generalizations in that essay, which I believe are unsupportable. Here is one of the worst:

But who is Osama bin Laden really? Let me rephrase that. What is Osama bin Laden? He's America's family secret. He is the American president's dark doppelganger. The savage twin of all that purports to be beautiful and civilised. He has been sculpted from the spare rib of a world laid to waste by America's foreign policy: its gunboat diplomacy, its nuclear arsenal, its vulgarly stated policy of "full-spectrum dominance", its chilling disregard for non-American lives, its barbarous military interventions, its support for despotic and dictatorial regimes, its merciless economic agenda that has munched through the economies of poor countries like a cloud of locusts. Its marauding multinationals who are taking over the air we breathe, the ground we stand on, the water we drink, the thoughts we think. Now that the family secret has been spilled, the twins are blurring into one another and gradually becoming interchangeable. (link)

She might have a point that the wrong of 9/11 is no worse than, for instance, the wrongs the U.S. has at times committed in the name of freedom or justice, or which have followed indirectly from its actions (as in, 100,000 dead Iraqi civilians since the beginning of the most recent war -- a war which didn't need to happen in the first place).

But I don't see the point in claiming that the two types of violence are "interchangeable," or that Osama Bin Laden is America's "family secret" and also its "doppleganger." No, he's not: they are separate evils, and merging them is sloppy thinking. And I don't see the point in bringing in multinational corporations -- their function is quite different from that of the U.S. military, even if some function as auxiliaries for military projects. But McDonald's and Microsoft are not the same as Halliburton, and the mere fact that all three have well-paid corporate executives does not make make them all evil.

I'm not that far from Roy on some issues of substance (at least in this particular essay; I do think many of her positions on other issues are absurd [see her comments last year on cell-phones in India, for instance]). But I'd rather describe things plainly, as they are, and without the breathless ramification of rhetoric that she seems to relish so much.

Semantic Tagging Vs. Search (Del.icio.us and CiteULike)

Over on the sidebar, you'll see three links, two of which are new:

"Clips blog" speaks for itself: just raw links to things that seem interesting in my RSS feeds. (Suffice it so say, that after a brief dalliance with Google Reader, I'm still using Bloglines.)

Del.icio.us is a service that many readers will likely be familiar with, though probably not everyone. It's also a kind of 'clippings' mechanism, though the idea is you store your favorites with tagged (keyword) references. Some people (Kerim) even use it as a way of housing an extended blogroll.

It might seem redundant to have semantic tagging when you can basically find anything you can think of with simple searches in Google or Yahoo. But del.icio.us seems to be most surprising when you're trying to find things that relate to what you're interested in, but that you wouldn't necessarily know to search for. The people who seem to have adopted it first are techies -- many software people seem to use del.icio.us to keep track of links to "helpful hints to debugging in DOT.NET" or "quick Linux hacks" (see Popular). But there's no reason why people interested in literature, art, and politics, can't also be using the service to connect to each other, and to find out about things via keywords.

Incidentally, the process of posting to del.icio.us becomes pretty easy with their handy Firefox extension. Once you've installed the extension, it just takes one click to add a post.

I'm still not 100% sure whether del.icio.us tags will really be a big-time revolution -- "the next phase of the internet" -- or simply a service that appeals to hard-core users (bloggers and the like). Del.icio.us is certainly growing fast, and especially so since they were acquired by Yahoo!, but their interface isn't exactly fun.

The title of this post might be somewhat misleading, since obviously I'm not suggesting that semantic tagging services like del.icio.us or Flickr are somehow going to make conventional search engines obsolete. At most, the two forms of accessing resources on the web will be complementary to each other. But there is an additional level of interactivity involved with tagging -- you leave a trail across the net (if you want to), which either you yourself or someone else could possibly make use of later.

Finally, a word on CiteULike. This is an academic-oriented service, that allows you to bookmark articles you've read online, including those that are behind university subscription databases -- such as Project Muse, JSTOR, EBSCOhost, etc.

I've just started playing around with CiteULike, and I'm not quite sure yet whether I'll be using it regularly. It might be a useful tool to get into a better discipline with regards to actually reading journal articles (instead of just doing searches when I'm working on an article or a book chapter). Like Del.icio.us, CiteULike allows you to share links to articles and view other people's articles, making it potentially easier to keep up with other people who might be doing research that relates to yours. And the "notes" function allows you to read people's thoughts on the articles they're reading. As with Del.icio.us, this service will only be of great value as a relational index if a large number of people in a given field are actually using the service regularly.

Again, I get the feeling that people in the sciences are using this extensively, while humanities folks have barely touched it.

Any thoughts on these services? And what do you think about Tagging vs. Search? Are there other tagging services you would recommend?

Clips blog @ Bloglines

My Del.icio.us

My CiteULike

"Clips blog" speaks for itself: just raw links to things that seem interesting in my RSS feeds. (Suffice it so say, that after a brief dalliance with Google Reader, I'm still using Bloglines.)

Del.icio.us is a service that many readers will likely be familiar with, though probably not everyone. It's also a kind of 'clippings' mechanism, though the idea is you store your favorites with tagged (keyword) references. Some people (Kerim) even use it as a way of housing an extended blogroll.

It might seem redundant to have semantic tagging when you can basically find anything you can think of with simple searches in Google or Yahoo. But del.icio.us seems to be most surprising when you're trying to find things that relate to what you're interested in, but that you wouldn't necessarily know to search for. The people who seem to have adopted it first are techies -- many software people seem to use del.icio.us to keep track of links to "helpful hints to debugging in DOT.NET" or "quick Linux hacks" (see Popular). But there's no reason why people interested in literature, art, and politics, can't also be using the service to connect to each other, and to find out about things via keywords.

Incidentally, the process of posting to del.icio.us becomes pretty easy with their handy Firefox extension. Once you've installed the extension, it just takes one click to add a post.

I'm still not 100% sure whether del.icio.us tags will really be a big-time revolution -- "the next phase of the internet" -- or simply a service that appeals to hard-core users (bloggers and the like). Del.icio.us is certainly growing fast, and especially so since they were acquired by Yahoo!, but their interface isn't exactly fun.

The title of this post might be somewhat misleading, since obviously I'm not suggesting that semantic tagging services like del.icio.us or Flickr are somehow going to make conventional search engines obsolete. At most, the two forms of accessing resources on the web will be complementary to each other. But there is an additional level of interactivity involved with tagging -- you leave a trail across the net (if you want to), which either you yourself or someone else could possibly make use of later.

Finally, a word on CiteULike. This is an academic-oriented service, that allows you to bookmark articles you've read online, including those that are behind university subscription databases -- such as Project Muse, JSTOR, EBSCOhost, etc.

I've just started playing around with CiteULike, and I'm not quite sure yet whether I'll be using it regularly. It might be a useful tool to get into a better discipline with regards to actually reading journal articles (instead of just doing searches when I'm working on an article or a book chapter). Like Del.icio.us, CiteULike allows you to share links to articles and view other people's articles, making it potentially easier to keep up with other people who might be doing research that relates to yours. And the "notes" function allows you to read people's thoughts on the articles they're reading. As with Del.icio.us, this service will only be of great value as a relational index if a large number of people in a given field are actually using the service regularly.

Again, I get the feeling that people in the sciences are using this extensively, while humanities folks have barely touched it.

Any thoughts on these services? And what do you think about Tagging vs. Search? Are there other tagging services you would recommend?

Had John Updike Been African...

Teju Cole is the current (and temporary) pseudonym of a rather nomadic blogger, who will be posting about his travels in Nigeria for a few weeks. One of his comments about getting access to good material caught my eye:

More than a little truth in this, I think. (Crap, maybe I should get out of Pennsylvania too...)

A Hint: If this interests you, you should read more of Teju Cole soon, before the blog disappears.

One morning as I walk down our street to where the Isheri Road goes under the Lagos-Sagamu Expressway Bridge, I witness a collision between two cars. The drivers both kill their engines in the middle of the road, jump out of their vehicles, and start beating each other up. Fists connecting with faces, right there in front of me. This is Lagos.

Well, this is wonderful, I think. Life hangs out here. The pungent details are all around me. Here's the material that can really hit a reader between the eyes. A gossip-lover's paradise.

One week later, I see another fight, at the very same spot. All the touts in the vicinity join in this one. Pandemonium, but a completely normal kind of pandemonium, that fizzles out after about ten minutes. End of brawl. Everyone goes back to their normal business. I suddenly feel sorry for all those who, as writers, have to ply their trade from some sleepy American suburb, writing divorce scenes symbolized by the very slow washing of dishes. Had John Updike been African, he would have won the Nobel Prize twenty years ago. I'm sure of it. His material killed him. Shillington, Pennsylvania simply didn’t measure up to his extravagant gifts. And sadder yet are those who don't even have a fraction of Updike's talent, and yet have to hoe the same arid patch for stories. I could cry of boredom just thinking about it.

More than a little truth in this, I think. (Crap, maybe I should get out of Pennsylvania too...)

A Hint: If this interests you, you should read more of Teju Cole soon, before the blog disappears.

"Incendiary Circumstances": Reviews and Links

Amitav Ghosh's new book of essays, Incendiary Circumstances, is out. It has gotten a number of reviews:

It's worth noting that a number of the essays in the new book can be found online for free:

Tsunami 1, Tsunami 2, and Tsunami 3.

"The Ghosts of Mrs. Gandhi" is on Ghosh's own website here.

A version of "No Greater Sorrow" is here.

"The Ghat of the Only World: Agha Shahid Ali in Brooklyn" is at The Nation.

And there may be others, but I don't want to discourage people from buying the book!

Time Magazine (via Abhi @ Sepia Mutiny)

LA Times (via Indian Writing)

San Francisco Chronicle (via Indian Writing)

Washington Post

It's worth noting that a number of the essays in the new book can be found online for free:

Tsunami 1, Tsunami 2, and Tsunami 3.

"The Ghosts of Mrs. Gandhi" is on Ghosh's own website here.

A version of "No Greater Sorrow" is here.

"The Ghat of the Only World: Agha Shahid Ali in Brooklyn" is at The Nation.

And there may be others, but I don't want to discourage people from buying the book!

Sonia Faleiro's Book/Podcast, and a Better Kind of Interview w/Vikram Chandra

Sonia Faleiro's book The Girl is out on Viking India. Sonia does a podcast of an excerpt on her blog, which is pretty damn cool.

Sonia also recently interviewed Vikram Chandra for Tehelka, and did not mention his big advance. (I groaned about this tendency in the Indian media last week)

Sonia also recently interviewed Vikram Chandra for Tehelka, and did not mention his big advance. (I groaned about this tendency in the Indian media last week)

Margaret Cho! Goes to India

Margaret Cho! She's so outrageous, so much more melodramatic than life, that even simply stating her name deserves an exclamation point: Cho!

(Other people in the exclamation-required category include Odetta! and Rekha!. Feel free to suggest further additions...)

Via Clancy, I caught links to Cho's (!) recent adventures in India. Some clichés, but also some very energetic and entertaining stream-of-consciousness writing:

My first instinct is to remind her to breathe. But then, she's right, it is odd: why do the speakers go on the outside of the Tata trucks?

Also amusing was this:

Chi! (Note: That is a joke in Hindi)

(Other people in the exclamation-required category include Odetta! and Rekha!. Feel free to suggest further additions...)

Via Clancy, I caught links to Cho's (!) recent adventures in India. Some clichés, but also some very energetic and entertaining stream-of-consciousness writing:

Yet with the way that there are no real lanes, and the sheer variety of the vehicles on the road (tuk-tuks belching out black clouds of diesel smoke to camouflage themselves and everyone else, scooters balancing entire families, possibly three generations on two wheels, bulbous, gas guzzling Ambassadors filled with white tourists arriving from the airport, filled with dread and regret, wanting to turn back immediately, donkey carts pulled by old, old donkeys and driven by even older men, bicycles loaded down with sugar cane and roti and babies, then the undisputed kings of the highways, the enormous Tata lorries, painted in hallucinatory colors, swirling orange and purple monstrosities, blaring some kind of insanely happy Indian pop music, as the speakers sit outside the vehicles, to keep the drivers awake, so I was told, making me think that they are called Tata because that is the last thing you see coming at you, a cheerful goodbye - “Ta-Ta!” before you are crushed underneath their fearsome wheels, cows, just wandering freely, eating garbage in the way of oncoming traffic, dogs and pigs weaving in and out of it all, along with pedestrians who bravely cross because this is all absolutely normal to them) I can’t believe I didn’t see more carnage on the street, that the asphalt didn’t glow red with blood. (link)

My first instinct is to remind her to breathe. But then, she's right, it is odd: why do the speakers go on the outside of the Tata trucks?

Also amusing was this:

I called down at our hotel in Delhi one too many times for toilet paper. “We just sent you two rolls already! What are you doing with it? You Americans try to wipe wipe wipe all your problems away. You cannot do that here!” (link)

Chi! (Note: That is a joke in Hindi)

Texture Words and Data-Mining: Two Examples (Woolf and Sassoon)

The following post is written for inclusion in The Valve's discussion of Franco Moretti's Graphs, Maps, and Trees.

It's a pleasant coincidence that Matt Kirschenbaum posted an introduction to Nora, the data-mining literary studies collaborative project he is involved with, just as I've been working on my own post on a proposed project to use search and semantic tagging (del.icio.us and other XML-based services) to study the representation of texture in literary texts. In his post, Matt asks:

The following is my own proposal for a very specific kind of linguistic data that could be gathered from searchable digital texts.

1. Texture

Some years ago I started a project on "texture words" for a seminar on Victorian literature, which I took with Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, and which Eve in turn had designed on the inspiration of her student Renu Bora. Bora's essay "Outing Texture" (published in the Duke Press anthology Novel Gazing) had worked out some interesting links between materialism (as in, Marxist historicism) and the sensory/sexual experience of Victorian material culture (as in, the world of fabric, fetish-objects, and touchable commodities).

Bora's essay has some very inspired moments -- as well as some potentially confusing "theory" -- but the most important thing he does for my purposes is define the concept of texture that I work with. Texture is:

My own interest is in the way texure is figured in literary language. From the 9 or 10 novels we read that term, I made lists of key texture words and organized them semantically, using my own rough (and admittedly idiosyncratic) classificatory scheme:

I call these and other words that look and sound like them "texture words." They have various functions in literary texts, which vary by genre and period, and any absolute generalization about them is likely to fail. (It's a big language.)

Instead of function, I tend to think about texture words in terms of value, which is various. First and foremost, texture words can describe physical textures in the world -- a building reduced to "rubble," or a "shiver" from cold. But texture words also provide a second-order value to writers, as a way of figuring perceptions or ideas that exist almost entirely in the mind: a "glimmer" of understanding, a "ripple" of pleasure. Texture can materialize a mode of being that might be difficult to represent. In the hands of sloppy writers, they can be a shortcut, or a way of remaining vague about what is meant. But in the hands of masters -- say, George Eliot or Henry James -- texture is an essential tool in navigating the ambiguity and confusion that intelligent human subjects (the protagonists of novels) generally inhabit.

It was 1997, so naturally I made a kind of web project out of this, some of which worked and some of which was probably a little silly. One component of the project that I still find useful is a starter raw material archive, associating the words above with particular passages in the novels in question: A-L, and M-Z. The archives could well be extended with reference to other works by the same authors, as well as thousands of other works of poetry and fiction that use these types of words to convey a sense of visual (and haptic) texture in literature. Ideally, the expanded version would be a collaboratively produced database, with chronological information as well as direct links to OED entries for each of the words. The material could be extracted and compiled relatively easily from thousands of digital texts that are already accessible through sites such as Project Gutenberg.

Ideally we would also have some of the cutting-edge niceties -- chief among them collaborative tools such as comments and a Wiki-like framework that allows any interested party to contribute. I'm especially optimistic about the possibilities of semantic tagging, which distributes the potential labor involved in organizing the data, and makes it useable for multiple purposes. For instance, I may be interested in "texture," while another scholar might be interested in "homoeroticism" or "railroads." Ideally, a fully tagged digital literary would make it relatively straightforward to find and produce linguistic data such as I am interested in with texture, but also provide bridges between different kinds of thematic inquiries.

* * * *

2. Working With Texture in a Brief Interpretive Reading (Virginia Woolf's The Voyage Out)

(Check out The Voyage Out Gutenberg etext.)

What has stayed with me from my earlier project is a small obsessive attention to words that signify texture: I prick up my ears when novelists and poets use words like "glimmer" or "shimmer," and compare notes with the way George Eliot or Henry James used it. For instance, Virginia Woolf's The Voyage Out (which I read for the first time only last year) seems heavily dependent on these texture words, which Woolf uses to convey both physical textures as well as the infinitely varied landscape of human emotion. So you have passages like the following:

The ship steadily encroaches on land, and the features of the shore gradually differentiate themselves from one another. Flatness turns to texture with proximity. And then the reversal: once the sense of space (the "great bay") is stable, an even closer kind of texture emerges, as the boats from shore "swarm" around the ship and there is the "thump" of feet on deck. This is Woolf doing an experience of texture that most people will be familiar with, though most of the time the experience of a changing scale of visual differentiation happens in a matter of seconds (in the air), so there is generally less time to contemplate than was available to people at sea.

But Woolf uses some of the same words in passages dealing with her characters' emotional lives as well, such as Rachel's traumatic first kiss at the hands of Richard Dalloway (a married older man). Forgive -- or enjoy, as appropriate -- the purplish prose:

Notice the way Woolf uses the word "scattered" at the end of this passage, to convey a sense that the intensity of the moment of the kiss has in effect dissipated, even as she marks a transformation: life now holds "infinite possibilities" for Rachel (though what those possibilities are remains unspecified). Both of these passages use images of visual texture, though in the second passage the visual textures are reflections of Rachel's feelings. But it's more than that: as one gets further into the novel it becomes apparent that Rachel experiences the world almost entirely through texture. In Lacanian jargon, we could say that she is a creature of Imaginary textures, while the Symbolic world of meanings and focused interpretations remains beyond her reach. She sees textures instead of the things themselves.

* * * *

3. Working With Texture Using a Quasi-Quantitative Method: Siegfried Sassoon's War Poems

(Check out Sassoon's War Poems at Gutenberg)

I'm teaching Pat Barker's Regeneration this spring, so I've been going through Siegfried Sassoon's poems to see what's there. And while it now appears to me that Sassoon isn’t perhaps the greatest of the war poets, he does have a distinctive voice and some very powerful poems (and he played a key role in nurturing the best of the war/anti-war poets of World War I, Wilfred Owen). However, his style is perhaps a little too recognizable: he tends to repeat themes and images a little too frequently. He also sometimes uses mixed metaphors in ways that might be deemed predictable (“flickering horror”; “blurred confusion”).

But Sassoon’s poems become interesting even as flawed, symptomatic artifacts of the war. The dense sound associations and intricate patterns Sassoon creates in his first two collections, The Huntsman and Other Poems and The Counter-Attack And Other Poems (recollected at War Poems in 1918) collectively provide a good example of the phenomenon of linguistic texture I was referring to above.

There are a few sound clusters that dominate the war poems in these books, and even simply enumerating them gives a powerful demonstration of Sassoon’s frame of mind: doom/gloom/glum/glimmer; grunt/gruff/mutter/thud; stumbling/ crumpling/ shuddering/ smothering/ smouldering/ hammering/ muttering/ muffling/ rumbling/ blundering; rotten/ sodden/ trodden; strangled; bleeding; choked/ crouched; creep.

There is an overwhelming tone of darkness, blindness, and paralysis in most of the poems, some of which were written while Sassoon was in "recovery" at Craiglockhart near the end of the war (of course, he was never really sick). There are of course poems that don’t fit the pattern, of which most are satirical political commentary on pro-war Englishmen, while a couple deal with natural imagery (in the model of Sassoon's earlier, genteel style). Of course, even these exceptions do contain texture words: “The Fathers” has the phrase "I watched them toddle through the door," while "Base Details" has "toddle safely home and die." "Toddle" is a texture word in a rather unusual sense: a walking texture, connoting a particularly soft movement of the legs. It sounds (and works) a fair bit like "waddle," except it strongly suggests infant-like movement. This is how Sassoon insults his rhetorical enemies -- the chicken hawks of World War I.

Sassoon’s texture words are generally found in his trench poems, of which an exemplary case might be "Prelude: The Troops," which also has the virtue of being short. Below, I've posed all of the texture words in the poem in bold:

This isn't the most 'textury' of Sassoon's poems -- it drifts away from the grimy, gloomy, muddy textures of the trenches in the first stanza to a more dramatic, funereal tone in the third, passing through a soft pastoral interlude in stanza two. For now, let's just focus on the dense cluster of texture words in that first stanza: "dim," "thinning," "gloom," "shudder," "drizzle," "sodden," "dull," "sunken," "haggard," and "grope."