In honor of Bloomsday, here (PDF) is a short, unpublished essay on the theme of fat in Ulysses. (See the post at The Valve for some more details.)

Last year's Bloomsday (100) was all hype. This year's will be all 'substance', if I have anything to say about it.

Postcolonial/Global literature and film, Modernism, African American literature, and the Digital Humanities.

Killing 'Democracy' in order to save it

No, not another rant about what goes on at Guantanamo Bay, though that would be a worthy topic.

Rather, it's about Microsoft, which is forbidding Chinese bloggers on MSN Spaces in China from using words like "Democracy," "Freedom," and "Taiwan Independence" in the titles of their blogs. The idea is to reduce the flags that appear to Beijing censors, and reduce the chances that the service will be banned entirely in China.

I like it -- it's reverse Orwell. You use double-speak not to silence freedom, but to ensure it.

Rather, it's about Microsoft, which is forbidding Chinese bloggers on MSN Spaces in China from using words like "Democracy," "Freedom," and "Taiwan Independence" in the titles of their blogs. The idea is to reduce the flags that appear to Beijing censors, and reduce the chances that the service will be banned entirely in China.

I like it -- it's reverse Orwell. You use double-speak not to silence freedom, but to ensure it.

In Defense of Coldplay (only, not so much the new album)

Jon Pareles' recent critical review of Coldplay's new album X&Y in the New York Times has so much praise of the band in it that it's hard to see what he doesn't like. (Or perhaps, it's easy to see what he doesn't like, but it's hard to believe that he means it.)

For starters:

This all seems true. Perfect pop melodies, and a hook in every song. It's why Coldplay is one of the few bands where people want the whole CD, not just the single from the radio.

Many bands have beautiful melodies -- the Doves, Engineers (a new band), and Elbow (a relatively obscure band), and Clinic all come to mind as comparable sounding bands who should be better known than they are. Then there's the old dinosaur called Radiohead, of course. And singer-songwriters like Elliott Smith and Rufus Wainwright are in the same folder in my feeling-melodic hard drive (though they have little in common with Coldplay musically, and both certainly supersede Coldplay in terms of originality). But nearly all of the names just mentioned have a tendency to get too arty after a certain point in their careers. I can appreciate Radiohead's recent CDs, but I can't listen to them more than twice. I listen to Clinic and the Doves much more, but only certain songs (for instance, Clinic's "For the Wars" off of Walking With Thee); there are several tracks that don't quite seem to go anywhere on all of these bands' albums.

What serious music critics don't like about Coldplay is precisely what I do like. Every song has structure: chorus, verse, bridge. Every song, that is, is a song. Pareles suggests that it might be a bit too robotic ("anything that distracts from the musical drama"), but I think of it -- again, in the pop idiom -- as well-focused writing and production. They know what they are trying to do, and they do it.

Pareles does make a valid criticism of Chris Martin's over-use of falsetto:

I have to accept this as a legitimate criticism. It's a predictable part of the show, and as such, the surprise of it has worn off. Still, I've tried to get my voice to do that falsetto, and it simply won't go there. Am I alone? How many men can do that with their voices? Chris Martin has a great voice, maudlin falsetto included. Why begrudge him the attempt to show it off?

On to the lyrics:

Here I think that Jon Pareles has it exactly backwards, at least on the first two CDs (X&Y does tend a bit more towards self-indulgence than the earlier albums did). Chris Martin's lyrical restraint is in fact one of the best things about Coldplay's first two albums, Parachutes and A Rush of Blood to the Head. The lyrics are simple, but even when they express very familiar feelings, they tend towards an intriguing abstraction. Take the hit "Yellow," which everyone is sick of hearing, even me. But here are the first two verses:

Yellow? (Read the rest of the lyrics here.) It's an almost-annoyingly simple song, with a melody that can quickly become cloying. But the lyrics remain just a little bit elusive, in a way that over-the-top love songs don't often manage to do (it's much less obvious than U2's "One", for instance). The saving grace is that word "yellow," which has no fixed referent that is evident to the listener. Especially with the reflexivity of the second verse, this is the exact opposite of self-indulgence or self-involvement. It's almost entirely impersonal.

Another example, from a song expressing a very different kind of feeling, is "A Rush of Blood to the Head," from the second album. Here are the opening verses:

This being the album Coldplay released not long after 9/11, one has to presume a connection to terrorism. Interestingly, what Coldplay is doing is not a "give peace a chance" type of message. It's more psychological: a song about the sociopathic kind of anger that sometimes leads young men to commit Acts of Violence Against Society. But it's not only about that, as the line "I'm gonna buy this place" ties the impulse to violence to the urge to dominate and subjugate, attributes as essential to American Capitalism as they are to acts of terrorism. Even Coldplay's political references are carefully controlled -- and just complex enough to be interesting.

Many other Coldplay songs fall in these parameters. They work out a good balance: all of it feels real, but not much of it is directly personal or socially overt. (There are no songs called "I love you Gwyneth," for instance.) If we're talking about self-pity, self-indulgence, and general emo-overload, a much better culprit would be Bright Eyes. Conor Oberst sure has a lot to say about his ex-girlfriends!

Two more paragraphs from Pareles full of criticisms that turn out to be compliments, and I'll quit:

Though Pareles means this as a set-up for his final takedown of what he calls Coldplay's "hokum," he manages to pinpoint some of Coldplay's greatest strengths along the way. Did anyone hear "Clocks" and not feel some admiration for the writer and the musicians who came up with it? And I don't think Coldplay's extremely studied production values necessarily represents the absence of "any glimmer of human frailty." It could just as easily be described as craftsmanship and care.

We did a lot of driving this past weekend, and got a good earful of X&Y. It's decent and listenable. It's especially heartening that they're sticking with pop, not getting into experimental art-rock or electronics (they are thinking more U2 and less Radiohead, which is fine by me). Still, the production is much more dense with instrumentation, louder and less intimate-sounding. The music sounds less personal -- more radio-friendly? -- and the shadings of U2's guitar and Pink Floyd production effects are sometimes a bit too obvious for my taste.

Despite its flaws X&Y shows that Coldplay know how to make an album that sounds like Coldplay, which is exactly what I was asking for. So sue me!

For starters:

Coldplay is admired by everyone - everyone except me.

It's not for lack of skill. The band proffers melodies as imposing as Romanesque architecture, solid and symmetrical. Mr. Martin on keyboards, Jonny Buckland on guitar, Guy Berryman on bass and Will Champion on drums have mastered all the mechanics of pop songwriting, from the instrumental hook that announces nearly every song they've recorded to the reassurance of a chorus to the revitalizing contrast of a bridge. Their arrangements ascend and surge, measuring out the song's yearning and tension, cresting and easing back and then moving toward a chiming resolution. Coldplay is meticulously unified, and its songs have been rigorously cleared of anything that distracts from the musical drama.

This all seems true. Perfect pop melodies, and a hook in every song. It's why Coldplay is one of the few bands where people want the whole CD, not just the single from the radio.

Many bands have beautiful melodies -- the Doves, Engineers (a new band), and Elbow (a relatively obscure band), and Clinic all come to mind as comparable sounding bands who should be better known than they are. Then there's the old dinosaur called Radiohead, of course. And singer-songwriters like Elliott Smith and Rufus Wainwright are in the same folder in my feeling-melodic hard drive (though they have little in common with Coldplay musically, and both certainly supersede Coldplay in terms of originality). But nearly all of the names just mentioned have a tendency to get too arty after a certain point in their careers. I can appreciate Radiohead's recent CDs, but I can't listen to them more than twice. I listen to Clinic and the Doves much more, but only certain songs (for instance, Clinic's "For the Wars" off of Walking With Thee); there are several tracks that don't quite seem to go anywhere on all of these bands' albums.

What serious music critics don't like about Coldplay is precisely what I do like. Every song has structure: chorus, verse, bridge. Every song, that is, is a song. Pareles suggests that it might be a bit too robotic ("anything that distracts from the musical drama"), but I think of it -- again, in the pop idiom -- as well-focused writing and production. They know what they are trying to do, and they do it.

Pareles does make a valid criticism of Chris Martin's over-use of falsetto:

Unfortunately, all that sonic splendor orchestrates Mr. Martin's voice and lyrics. He places his melodies near the top of his range to sound more fragile, so the tunes straddle the break between his radiant tenor voice and his falsetto. As he hops between them -- in what may be Coldplay's most annoying tic -- he makes a sound somewhere between a yodel and a hiccup.

I have to accept this as a legitimate criticism. It's a predictable part of the show, and as such, the surprise of it has worn off. Still, I've tried to get my voice to do that falsetto, and it simply won't go there. Am I alone? How many men can do that with their voices? Chris Martin has a great voice, maudlin falsetto included. Why begrudge him the attempt to show it off?

On to the lyrics:

And the lyrics can make me wish I didn't understand English. Coldplay's countless fans seem to take comfort when Mr. Martin sings lines like, "Is there anybody out there who / Is lost and hurt and lonely too," while a strummed acoustic guitar telegraphs his aching sincerity. Me, I hear a passive-aggressive blowhard, immoderately proud as he flaunts humility. "I feel low," he announces in the chorus of "Low," belied by the peak of a crescendo that couldn't be more triumphant about it.

Here I think that Jon Pareles has it exactly backwards, at least on the first two CDs (X&Y does tend a bit more towards self-indulgence than the earlier albums did). Chris Martin's lyrical restraint is in fact one of the best things about Coldplay's first two albums, Parachutes and A Rush of Blood to the Head. The lyrics are simple, but even when they express very familiar feelings, they tend towards an intriguing abstraction. Take the hit "Yellow," which everyone is sick of hearing, even me. But here are the first two verses:

Look at the stars,

Look how they shine for you,

And everything you do,

Yeah, they were all yellow.

I came along,

I wrote a song for you,

And all the things you do,

And it was called "Yellow."

Yellow? (Read the rest of the lyrics here.) It's an almost-annoyingly simple song, with a melody that can quickly become cloying. But the lyrics remain just a little bit elusive, in a way that over-the-top love songs don't often manage to do (it's much less obvious than U2's "One", for instance). The saving grace is that word "yellow," which has no fixed referent that is evident to the listener. Especially with the reflexivity of the second verse, this is the exact opposite of self-indulgence or self-involvement. It's almost entirely impersonal.

Another example, from a song expressing a very different kind of feeling, is "A Rush of Blood to the Head," from the second album. Here are the opening verses:

He said I'm gonna buy this place and burn it down

I'm gonna put it six feet underground

He said "I'm gonna buy this place and watch it fall

Stand here beside me baby in the crumbling walls

Oh I'm gonna buy this place and start a fire

Stand here until I fill all your heart's desires

Because I'm gonna buy this place and see it burn

Do back the things it did to you in return

He said I'm gonna buy a gun and start a war

If you can tell me something worth fighting for

Oh and I'm gonna buy this place that's what I said

Blame it upon a rush of blood to the head

This being the album Coldplay released not long after 9/11, one has to presume a connection to terrorism. Interestingly, what Coldplay is doing is not a "give peace a chance" type of message. It's more psychological: a song about the sociopathic kind of anger that sometimes leads young men to commit Acts of Violence Against Society. But it's not only about that, as the line "I'm gonna buy this place" ties the impulse to violence to the urge to dominate and subjugate, attributes as essential to American Capitalism as they are to acts of terrorism. Even Coldplay's political references are carefully controlled -- and just complex enough to be interesting.

Many other Coldplay songs fall in these parameters. They work out a good balance: all of it feels real, but not much of it is directly personal or socially overt. (There are no songs called "I love you Gwyneth," for instance.) If we're talking about self-pity, self-indulgence, and general emo-overload, a much better culprit would be Bright Eyes. Conor Oberst sure has a lot to say about his ex-girlfriends!

Two more paragraphs from Pareles full of criticisms that turn out to be compliments, and I'll quit:

Coldplay reached its musical zenith with the widely sampled piano arpeggios that open "Clocks": a passage that rings gladly and, as it descends the scale and switches from major to minor chords, turns incipiently mournful. Of course, it's followed by plaints: "Tides that I tried to swim against / Brought me down upon my knees."

On "X&Y," Coldplay strives to carry the beauty of "Clocks" across an entire album - not least in its first single, "Speed of Sound," which isn't the only song on the album to borrow the "Clocks" drumbeat. The album is faultless to a fault, with instrumental tracks purged of any glimmer of human frailty. There is not an unconsidered or misplaced note on "X&Y," and every song (except the obligatory acoustic "hidden track" at the end, which is still by no means casual) takes place on a monumental soundstage.

Though Pareles means this as a set-up for his final takedown of what he calls Coldplay's "hokum," he manages to pinpoint some of Coldplay's greatest strengths along the way. Did anyone hear "Clocks" and not feel some admiration for the writer and the musicians who came up with it? And I don't think Coldplay's extremely studied production values necessarily represents the absence of "any glimmer of human frailty." It could just as easily be described as craftsmanship and care.

We did a lot of driving this past weekend, and got a good earful of X&Y. It's decent and listenable. It's especially heartening that they're sticking with pop, not getting into experimental art-rock or electronics (they are thinking more U2 and less Radiohead, which is fine by me). Still, the production is much more dense with instrumentation, louder and less intimate-sounding. The music sounds less personal -- more radio-friendly? -- and the shadings of U2's guitar and Pink Floyd production effects are sometimes a bit too obvious for my taste.

Despite its flaws X&Y shows that Coldplay know how to make an album that sounds like Coldplay, which is exactly what I was asking for. So sue me!

Kiran Ahluwalia @ Joe's Pub

Sometimes my life is just one endless debate over hybridity/fusion. Last night was the latest chapter, with Kiran Ahluwalia's CD release performance at Joe's Pub in New York.

Ahluwalia sings Ghazals and Punjabi folk songs, mainly in a traditional style. (According to her website, she studied the art of Ghazal for several years in Hyderabad with a teacher named Vithal Rao, "one of the last living court musicians of the Nizam (King) of Hyderabad.") She has a remarkable, strong, unique voice. For that alone, I strongly recommend her music.

The difference -- and perhaps, the controversy -- is in her band, which includes western guitar and bass, and has a bit of a jazz sensibility. There is also just a hint of jazz in Ahluwalia's voice in some tracks. Nothing too obvious, but it's there in her live rendition of songs like "Rabh da Roop" (the CD version is a little different -- more "asli"). A traditional Punjabi version might really play up the melodrama of the song ("My friend, I have found my love/ but lost myself./ The intoxication of my passion/ overwhelmed me/ and I lost myself."). But in Ahluwalia's rendition it still comes across as just a little playful.

I have to admit that I like the lightness. I have a few ghazal CDs -- mainly Jagjit & Chitra and Pankaj Udhas -- but I don't listen to them often anymore. Ghazals can be heavy, and slow -- lugubrious, even. While a cynic might say that Ahluwalia has a jazz guitarist because it makes the music more legible to Americans and ABCDs, one could just as easily say that it brings the rhythm up, and makes things more lively. (And while I'm at it, I should point out there's plenty of fusion happening in India itself right now -- listen, for instance, to the great debut CD from Rabbi Sher-Gil.)

Not everyone likes what Ahluwalia is doing. I ran into a couple of old friends at the show -- both ABCDs. They said they didn't especially like the fusion elements; somehow it made the music seem a little light. One quip that stuck in my mind was their sense that the fusion wasn't "necessary," and I can see what they mean. You could sing ghazals the way Jagjit & Chitra do it, or do Punjabi songs the way someone like Abida Parveen sings them (or indeed, the way Jagjit & Chitra did, on occasion). In traditional renditions, you hear strong emotion, and voices straining with longing at every note. But Ahluwalia never quite goes there. She sings her songs the way western folk singers might sing their songs -- with feeling, but with a certain restraint that comes, I suspect, from a commitment to technical precision: it's more important that I hit every note just right, than it is that you believe that I'm really feeling the emotion of this song right now.

My friends might have a point about the "necessity" of fusion in the formal sense. But in a more practical sense, they're definitely wrong. Without the fusion element, there is no to arrange a CD debut performance at an elite venue like Joe's Pub. Without fusion, also, you don't get a major record contract with a prominent World Music label, and you don't get a room full of sophisticated New Yorkers (half of the audience was non-Indian) loving your music. To put it quite directly, without fusion, there is no way Kiran Ahluwalia and her band could get paid like professional musicians at an early phase in their career.

I myself only heard of Kiran Ahluwalia on Tuesday, listening to WNYC's "Soundcheck" as I was driving somewhere. You can listen to the show here. (She comes in at 26:30; the first half of the show is a Canadian band called The Dears.)

[Incidentally, I had a similar debate with my cousin last year, when we went to see Vishal Vaid at the same venue. See that post here]

MP3 file, from Radio Open Source w/YT

The MP3 of the radio interview with Amitav Ghosh is here, at the wonderful Internet Archive.

I would also recommend the conversation on the same program the following night, with Professor Kim Scheppele, on putting the recent referenda on the EU Constitution in perspective. She's worked with the Afghanis as a consultant on their constitution, and is going to be working with the Iraqis this summer during their Constitutional Assembly.

You can also find all of the other downloadable episodes of Radio Open Source that have made it through the Internet Archive's cue by doing a search for "Christopher Lydon" at their site. Thus far it looks like 5 episodes of the show in all are available. (Incidentally, their search engine is a little screwy; you get different results if you run the search multiple times!)

I would also recommend the conversation on the same program the following night, with Professor Kim Scheppele, on putting the recent referenda on the EU Constitution in perspective. She's worked with the Afghanis as a consultant on their constitution, and is going to be working with the Iraqis this summer during their Constitutional Assembly.

You can also find all of the other downloadable episodes of Radio Open Source that have made it through the Internet Archive's cue by doing a search for "Christopher Lydon" at their site. Thus far it looks like 5 episodes of the show in all are available. (Incidentally, their search engine is a little screwy; you get different results if you run the search multiple times!)

Book Meme (the buck stops here)

Kitabkhana had tagged me last week to do this book meme thing. Someone else did too, recently, though I can't quite figure out who.

I'm going to do it, but -- bad luck! -- I'm going to break the chain, and refrain from tagging anyone else. (If you would like to do a meme inspired by this one, send me an email or drop me a comment, and I will retro-actively tag you.)

1. Total Number of books you own

No idea. I got married two years ago, which means in addition to my office full of books, my study at home full of books, and a living room with a fair number of books, my wife's books are there -- most of them on a large bookshelf in the bedroom. So in addition to predictable titles like Gauri Viswanathan's Outside the Fold: Conversion, Modernity, and Belief, John Hawley's Sati: The Blessing and the Curse, and Michael Walzer's On Toleration, for all practical purposes I now also posses a rather intimidating shelf of books called things like Data Structures Using C and C++, Local Area High Speed Networks, and ATM & MPLS Theory & Application. Top that, eclectic readers!

2. Last Book I Bought

I'm not sure which I bought more recently -- Andrea Levy's Small Island or a massive anthology called Theory's Empire (to be discussed shortly on The Valve).

When I bought the Levy, I also picked up a small pile of books from the "extras" bin ($5) at the Barnes & Noble near where I live: Jasper Fiorde's The Eyre Affair (heard it was funny), Anthony Arthur's Literary Feuds (I love me some literary feuds), Peter Gay's Savage Reprisals: Bleak House, Madame Bovary, Buddenbrooks, and a biography of Flaubert by Geoffrey Wall.

Like Hurree of Kitabkhana, I evidently buy books by the bushel.

3. Last Book I Read

On Sunday and Monday I re-read Amitav Ghosh's The Hungry Tide, as part of preparing for what turned out to be a very brief role in a radio conversation with Ghosh Monday evening. The book stands up to a second reading, though this time I noticed that I was much more interested in Ghosh's use of science and religion -- the dolphins and Bon Bibi -- than I was in the lives and loves of the main characters. No complaints on that, though: I am in very good shape if I find myself at a cocktail party talking to a Cetologist anytime soon.

Last week, with great difficulty, I worked my way through William E. Connelly's Why I Am Not A Secularist, a book I should have read two years ago. (I tried earlier, but I couldn't follow the argument.) He makes some really good points, even if I ultimately disagree with him (and Talal Asad). I may do a blog post on this at some point to spell out what I mean a bit more.

4. Five Books That Mean A Lot To Me

I'm going to limit this to "five books that were important to me when I was in college." Otherwise, readers are likely to be treated to a long list of obscure works of literary criticism. (I'll save that list for "Book Meme: Pedantry Edition," which will undoubtedly be going around next month)

A. Midnight's Children was the inspiration for my undergraduate thesis (on Salman Rushdie). Though it wasn't assigned to me it was the experience of developing a comprehensive argument about this book that gave me the confidence to try for graduate school in literature. Else, I would have ended up in grad school in biology, or law school, or writing computer software... Daaamn youuuuu Ruuuuuuuuuushdiiiiiie!!! [in my best Charlton Heston voice]

B. Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse I got my first "A+" at Cornell for a paper I wrote on this novel. I subsequently lost the paper, but Woolf made so much sense to me that I had this novel more or less in ready memory for many years. It was still pretty much fresh when I read it again to teach during my first semester as a professor. When I first read it, the book opened up a world. The second time was quite different: it was my feeling of loyalty to Woolf's philosophical framework that inspired me to get my act together as a teacher during an otherwise very difficult semester. (9/11 was in the air; I was paranoid and depressed.)

C. Deleuze-Guattari's Anti-Oedipus. It seems strange given that I never talk about Deleuze-Guattari, but the explosive freedom of their theoretical method lit a fire in my brain when I was 19. I think I might summarize it like this: Deleuze and Guattari argue that all established methods for understanding the human role in the material world -- from Descartes to Freud -- are wrong, expressions of a kind of philosophical totalitarianism. What you need is a completely different, rigorously anti-authoritarian basis for knowledge, based on a non-object they call the "body without organs." Deleuze/Guattari are responsible for a slew of theoretical buzzwords that people still play with, such as the "rhizome," the "nomad," "deterritorialization," the "smooth and the striated," and "molar/molecular" [as a political metaphor]. It all sounds cool, until you try and explain any of the terms to someone who is not a "theorist." I now find the "body without organs" to incoherent (or at least, useless), and I believe all of the other Deleuzian terms are expressible in simpler terms.

D. Plato's The Republic. This was an inspiration, but in rather the opposite manner from Anti-Oedipus. I took a course in the Comp. Lit. department on something to do with philosophy and literature. The Professor, whose name I have unfortunately forgotten, was an elderly woman of a rather conservative bent, who was often a little frustrated by the small band of political radicals (myself included) that landed up in her class. We wanted to talk about communism, feminism, and Lacanian interpretations of the Allegory of the Cave. She wanted us to interpret the book. Through her demand that we be rigorous, I really learned a fair bit about how to read Plato.

E. Octavia Butler's Bloodchild. It's still my favorite work of science fiction. Icky, yes. But brilliant.

Tag Five People And Have Them Do This On Their Blogs.

No, I refuse. But again, if you would like to do one of these, let me know (send me the link), and I will retro-actively tag you.

I'm going to do it, but -- bad luck! -- I'm going to break the chain, and refrain from tagging anyone else. (If you would like to do a meme inspired by this one, send me an email or drop me a comment, and I will retro-actively tag you.)

1. Total Number of books you own

No idea. I got married two years ago, which means in addition to my office full of books, my study at home full of books, and a living room with a fair number of books, my wife's books are there -- most of them on a large bookshelf in the bedroom. So in addition to predictable titles like Gauri Viswanathan's Outside the Fold: Conversion, Modernity, and Belief, John Hawley's Sati: The Blessing and the Curse, and Michael Walzer's On Toleration, for all practical purposes I now also posses a rather intimidating shelf of books called things like Data Structures Using C and C++, Local Area High Speed Networks, and ATM & MPLS Theory & Application. Top that, eclectic readers!

2. Last Book I Bought

I'm not sure which I bought more recently -- Andrea Levy's Small Island or a massive anthology called Theory's Empire (to be discussed shortly on The Valve).

When I bought the Levy, I also picked up a small pile of books from the "extras" bin ($5) at the Barnes & Noble near where I live: Jasper Fiorde's The Eyre Affair (heard it was funny), Anthony Arthur's Literary Feuds (I love me some literary feuds), Peter Gay's Savage Reprisals: Bleak House, Madame Bovary, Buddenbrooks, and a biography of Flaubert by Geoffrey Wall.

Like Hurree of Kitabkhana, I evidently buy books by the bushel.

3. Last Book I Read

On Sunday and Monday I re-read Amitav Ghosh's The Hungry Tide, as part of preparing for what turned out to be a very brief role in a radio conversation with Ghosh Monday evening. The book stands up to a second reading, though this time I noticed that I was much more interested in Ghosh's use of science and religion -- the dolphins and Bon Bibi -- than I was in the lives and loves of the main characters. No complaints on that, though: I am in very good shape if I find myself at a cocktail party talking to a Cetologist anytime soon.

Last week, with great difficulty, I worked my way through William E. Connelly's Why I Am Not A Secularist, a book I should have read two years ago. (I tried earlier, but I couldn't follow the argument.) He makes some really good points, even if I ultimately disagree with him (and Talal Asad). I may do a blog post on this at some point to spell out what I mean a bit more.

4. Five Books That Mean A Lot To Me

I'm going to limit this to "five books that were important to me when I was in college." Otherwise, readers are likely to be treated to a long list of obscure works of literary criticism. (I'll save that list for "Book Meme: Pedantry Edition," which will undoubtedly be going around next month)

A. Midnight's Children was the inspiration for my undergraduate thesis (on Salman Rushdie). Though it wasn't assigned to me it was the experience of developing a comprehensive argument about this book that gave me the confidence to try for graduate school in literature. Else, I would have ended up in grad school in biology, or law school, or writing computer software... Daaamn youuuuu Ruuuuuuuuuushdiiiiiie!!! [in my best Charlton Heston voice]

B. Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse I got my first "A+" at Cornell for a paper I wrote on this novel. I subsequently lost the paper, but Woolf made so much sense to me that I had this novel more or less in ready memory for many years. It was still pretty much fresh when I read it again to teach during my first semester as a professor. When I first read it, the book opened up a world. The second time was quite different: it was my feeling of loyalty to Woolf's philosophical framework that inspired me to get my act together as a teacher during an otherwise very difficult semester. (9/11 was in the air; I was paranoid and depressed.)

C. Deleuze-Guattari's Anti-Oedipus. It seems strange given that I never talk about Deleuze-Guattari, but the explosive freedom of their theoretical method lit a fire in my brain when I was 19. I think I might summarize it like this: Deleuze and Guattari argue that all established methods for understanding the human role in the material world -- from Descartes to Freud -- are wrong, expressions of a kind of philosophical totalitarianism. What you need is a completely different, rigorously anti-authoritarian basis for knowledge, based on a non-object they call the "body without organs." Deleuze/Guattari are responsible for a slew of theoretical buzzwords that people still play with, such as the "rhizome," the "nomad," "deterritorialization," the "smooth and the striated," and "molar/molecular" [as a political metaphor]. It all sounds cool, until you try and explain any of the terms to someone who is not a "theorist." I now find the "body without organs" to incoherent (or at least, useless), and I believe all of the other Deleuzian terms are expressible in simpler terms.

D. Plato's The Republic. This was an inspiration, but in rather the opposite manner from Anti-Oedipus. I took a course in the Comp. Lit. department on something to do with philosophy and literature. The Professor, whose name I have unfortunately forgotten, was an elderly woman of a rather conservative bent, who was often a little frustrated by the small band of political radicals (myself included) that landed up in her class. We wanted to talk about communism, feminism, and Lacanian interpretations of the Allegory of the Cave. She wanted us to interpret the book. Through her demand that we be rigorous, I really learned a fair bit about how to read Plato.

E. Octavia Butler's Bloodchild. It's still my favorite work of science fiction. Icky, yes. But brilliant.

Tag Five People And Have Them Do This On Their Blogs.

No, I refuse. But again, if you would like to do one of these, let me know (send me the link), and I will retro-actively tag you.

Follow-up From Yesterday: Thoughts on India, Iraq, Globalization, and "Empire"

Well, I did my best with my two minutes of radio fame. [Update: a downloadable MP3 is here]

In response to the question "What is the message from India," I said that there is no one message. India is way too complicated for that to even be a very productive question. It depends where you look, how you look, and who you talk to. I wish I would have had time to say a bit more:

For instance, for India’s poor, globalization has been of little consequence. The poorest segments of Indian society are still by and large without access to reliable electricity, clean water, education, or medical care. India’s per capita income is still $2,600 in purchasing power, according to the UNDP. The country is ranked 127th in the world in the UNDP’s development index. Adult literacy is at 60% according to the Indian census. And while there has been some progress, there’s no question that the sheer numbers of people who are living in conditions of poverty should be of grave concern to people all over the world.

Dilip D’Souza has reported on this in many of his stories in the Indian media. He’s been especially compelling on the plight of the people who live in the shantytowns of Bombay/Mumbai -– where something like half of the city live in illegal tenements that are routinely torn down by city authorities (only to be immediately rebuilt). A staggering number of people spend their entire lives in abysmal circumstances. (A sense of the surreal life of the chawls is also quite prevalent in Maximum City.)

We can perhaps blame some of these failures on western policies regarding India, but I don’t think it’s really sufficient. A much bigger factor has been the government’s lack of responsiveness, and its lack of vision about how to address the problems that are internal to India.

* * * * * *

But that's not the only story, and I think it's a mistake to only dwell on the negative. (The tenor of last night's conversation drifted in that direction.) I tried to offer some slightly more upbeat comments... here's what I should have said:

There is a new confidence, a new passion for entrepreneurialism in many different fields. Obviously the best known of these is the high tech industry -– computers, software, the internet. But you also see it happening in fields such as medicine, biotechnology, even space exploration. And of course you see it in literature, with a new crop of writers that is doing pretty amazing work writing in India itself.

The old idea that a well-educated person with talent and ambition had to leave India in order to get anywhere is fading. There is a trend where a small number of people who emigrated some years ago are actually returning to India to start businesses, or manage the Indian offices for major multinational corporations. The numbers of this reverse drain ("brain gain") are relatively small, but I suspect it will pick up, and have some long-term benefits for India’s talent pool.

There’s been some talk that because much of the work created in recent years via globalization is "back-office" work –- call-centers, for example -– the benefits for India will end up being quite limited. The sociologiest Vijay Prashad has even used the expression "high tech coolies" to suggest that while people who work at various kinds of outsourcing jobs are very well paid relative to the national average, they are essentially doing menial work that Americans don’t really want to do. There is a danger of that happening, but it seems to me that the picture is much more complicated than that, and I think Prashad has been mistaken in using that term. The call center phenomenon is only part of it. More and more of the outsourcing work is high quality employment. Companies like Microsoft and Intel increasingly depend on Indian programmers not just to write the basic code, but to develop large components of their fundamental products.

It is increasingly possible for middle class people in India to have very fulfilling careers in India itself, doing work that is at once challenging and meaningful, and where they themselves have a sense of command over their own destinies. It’s a major change from the era when office jobs were men sat, drank chai, and took bribes -- where not much of substance got done, and where ambition and innovation were stifled at every turn. Some of that culture is still there (one continues to hear complaints about India's Ocean of Red Tape), but a growing number of Indians in the current generation are fed up with it.

But again, it's a mistake to get carried away with optimism. The other set of problems -- those linked to poverty -- still remain. Since the government is unlikely to imagine any new way of dealing with entrenched problems, I have some hope that the younger generation will start to think beyond themselves, and use the new ethos that is emerging to improve the greater common good in ways that will benefit India’s large populations of both urban and rural poor. I would love to see an entrepeneurial attitude to fighting illiteracy and unemployment.

In short, though some people are worried about Western Imperialism, what is going to be more important in the long run is what Indians can do for themselves.

* * * * * *

Speaking of Empire, I’m not convinced that it’s appropriate to talk about American imperialism or "American empire" in the context of India. There are certain disturbing parallels between the recent Iraq war and the British Raj -– Ghosh has written about them, in the New Yorker (an article that is available at his website) but for me it’s not really a strong point for historical comparison -- it's more like a historical metaphor.

And I was a little disappointed that Amitav Ghosh seems to be essentially where he was at the start of the recent Iraq invasion. Here is how he opened the essay from the March 2003 New Yorker:

It's a very nicely written opening, but is it still a relevant metaphor for the current situation? At best, this is a caution for Americans on the verge of war. In the conversation on the radio last night, Ghosh followed up by alluding to Gandhi, and reminding us that freedom can't be instilled at gunpoint. All of which was said, correctly, by many on the left in the build-up to war. But I don't think it's a useful sentiment two years later; some things have changed. Like the Democratic presidential candidates in the last election, we need to apply ourselves to the new reality; we cannot effectively 'run' against a war that has already happened. I believe that in some fundamental sense we have to find a way to accept the American occupation, though we can continue to draw attention to the potential for further exploitation of the Iraqi people.

How to read what is happening in Iraq today is a vexed question. It does seem that the new government is slowly establishing itself, and there are some hints that the insurgents are slowly being rounded up. Do we really believe that a stable Iraqi government can't survive the inevitable withdrawal of American forces? And would we still call then this an exercise in "Imperialism"? Since I do believe that US troops will withdraw in the next 2-3 years, I don't think the term is applicable in the territorial sense. The US will, admittedly, begin to demand economic privileges from the new Iraqi government with regards to access to oil, but that is an economic relationship. It's an exploitative relationship, and not a good thing for ordinary Iraqis (or, for that matter, for ordinary Americans). But we should employ a different word to describe it.

Getting back to India. Christopher Lydon asked me why there hasn't been more outrage about America's Iraq adventure in the postcolonial world.

What I said was, some Indians did in fact protest this war -- Ghosh's piece in the New Yorker certainly had an impact, for instance. But these days most of India's intellectuals are, correctly, more concerned with the problems that preoccupy India itself than they are with George Bush's latest follies. It's a classic American fallacy to think that everyone in the world is worried just about America!

What I should have said was something along these lines: there is in fact a great deal of diversity of thought in India about this war, and the best attitude for India to take in response. Some might see it as a naked display of American super-dominance on the geopolitical stage, built on lies, and a deeply corrupt enterprise from start to finish. (Oh wait, that's how I see it...) But others in India's new generation would take a more pragmatic stance: We weren't happy that you started this war, but now that you have, is there any way I can make money out of it?

In response to the question "What is the message from India," I said that there is no one message. India is way too complicated for that to even be a very productive question. It depends where you look, how you look, and who you talk to. I wish I would have had time to say a bit more:

For instance, for India’s poor, globalization has been of little consequence. The poorest segments of Indian society are still by and large without access to reliable electricity, clean water, education, or medical care. India’s per capita income is still $2,600 in purchasing power, according to the UNDP. The country is ranked 127th in the world in the UNDP’s development index. Adult literacy is at 60% according to the Indian census. And while there has been some progress, there’s no question that the sheer numbers of people who are living in conditions of poverty should be of grave concern to people all over the world.

Dilip D’Souza has reported on this in many of his stories in the Indian media. He’s been especially compelling on the plight of the people who live in the shantytowns of Bombay/Mumbai -– where something like half of the city live in illegal tenements that are routinely torn down by city authorities (only to be immediately rebuilt). A staggering number of people spend their entire lives in abysmal circumstances. (A sense of the surreal life of the chawls is also quite prevalent in Maximum City.)

We can perhaps blame some of these failures on western policies regarding India, but I don’t think it’s really sufficient. A much bigger factor has been the government’s lack of responsiveness, and its lack of vision about how to address the problems that are internal to India.

* * * * * *

But that's not the only story, and I think it's a mistake to only dwell on the negative. (The tenor of last night's conversation drifted in that direction.) I tried to offer some slightly more upbeat comments... here's what I should have said:

There is a new confidence, a new passion for entrepreneurialism in many different fields. Obviously the best known of these is the high tech industry -– computers, software, the internet. But you also see it happening in fields such as medicine, biotechnology, even space exploration. And of course you see it in literature, with a new crop of writers that is doing pretty amazing work writing in India itself.

The old idea that a well-educated person with talent and ambition had to leave India in order to get anywhere is fading. There is a trend where a small number of people who emigrated some years ago are actually returning to India to start businesses, or manage the Indian offices for major multinational corporations. The numbers of this reverse drain ("brain gain") are relatively small, but I suspect it will pick up, and have some long-term benefits for India’s talent pool.

There’s been some talk that because much of the work created in recent years via globalization is "back-office" work –- call-centers, for example -– the benefits for India will end up being quite limited. The sociologiest Vijay Prashad has even used the expression "high tech coolies" to suggest that while people who work at various kinds of outsourcing jobs are very well paid relative to the national average, they are essentially doing menial work that Americans don’t really want to do. There is a danger of that happening, but it seems to me that the picture is much more complicated than that, and I think Prashad has been mistaken in using that term. The call center phenomenon is only part of it. More and more of the outsourcing work is high quality employment. Companies like Microsoft and Intel increasingly depend on Indian programmers not just to write the basic code, but to develop large components of their fundamental products.

It is increasingly possible for middle class people in India to have very fulfilling careers in India itself, doing work that is at once challenging and meaningful, and where they themselves have a sense of command over their own destinies. It’s a major change from the era when office jobs were men sat, drank chai, and took bribes -- where not much of substance got done, and where ambition and innovation were stifled at every turn. Some of that culture is still there (one continues to hear complaints about India's Ocean of Red Tape), but a growing number of Indians in the current generation are fed up with it.

But again, it's a mistake to get carried away with optimism. The other set of problems -- those linked to poverty -- still remain. Since the government is unlikely to imagine any new way of dealing with entrenched problems, I have some hope that the younger generation will start to think beyond themselves, and use the new ethos that is emerging to improve the greater common good in ways that will benefit India’s large populations of both urban and rural poor. I would love to see an entrepeneurial attitude to fighting illiteracy and unemployment.

In short, though some people are worried about Western Imperialism, what is going to be more important in the long run is what Indians can do for themselves.

* * * * * *

Speaking of Empire, I’m not convinced that it’s appropriate to talk about American imperialism or "American empire" in the context of India. There are certain disturbing parallels between the recent Iraq war and the British Raj -– Ghosh has written about them, in the New Yorker (an article that is available at his website) but for me it’s not really a strong point for historical comparison -- it's more like a historical metaphor.

And I was a little disappointed that Amitav Ghosh seems to be essentially where he was at the start of the recent Iraq invasion. Here is how he opened the essay from the March 2003 New Yorker:

During the past few months, much has been said and written on the subject of a "new American empire." This term, however, is a misnomer. If the Iraq war is to be seen as a kind of imperial venture, then the project is neither new nor purely American. What President Bush likes to call the "coalition of the willing" is dominated, after all, by America, Britain, and Australia - three English-speaking countries whose allegiances are rooted not just in a shared culture and common institutions but also in a shared history of territorial expansion. Seen in this light, the alignment is only the newest phase in the evolution of the most potent political force of the last two centuries: the Anglophone empire.

I am an Indian, and my history has been shaped as much by the institutions of this empire as by a long tradition of struggle against them. Now I live in New York; for me, the September 11th attacks and their aftermath were filled with disquieting historical resonances. I was vividly reminded, for example, of the Indian uprising of 1857, an event known to the British as the Great Indian Mutiny. That year, in Kanpur, a busy trading junction beside the Ganges, several hundred defenseless British civilians, including women and children, were cut down in an orgy of blood lust by Indians loyal to a local potentate, Nana Sahib. Many of the Indians involved in the rebellion were erstwhile soldiers of the empire who had been seized by nihilistic ideas. The rebels' methods were so extreme that Indian moderates were torn between sympathy, revulsion, and fear. Many Indians chose to distance themselves from the uprising. Others went so far as to join hands with the British in the two violent years that followed the rebellion. A similar process is clearly under way in today's Middle East, where Islamist fundamentalism has inflamed some Arabs while alienating others.

The phrase "shock and awe," used by the United States military to describe the initial aerial attack on Baghdad, provided another reminder of the 1857 uprising in India. In the aftermath of the mutiny, the British mounted a campaign to create terror and awe among rebel forces throughout the Indian subcontinent. The road from Kanpur to Allahabad was lined with the corpses of Indian soldiers who had been hanged; there were public displays of rebels being shot from cannons. British soldiers sacked cities across the north of India. The instruments of state were deployed in such a way as to reward allies and punish areas and populations that had supported the rebels. The effects of these policies were felt for generations and can, arguably, still be observed in the disparities that divide, say, the relatively affluent region of Punjab and the impoverished state of Bihar.

The right and wrong of the British actions are not at issue here. Nor do I want to overstate the analogy to the present circumstances; the "coalition of the willing" is clearly not going to use nineteenth-century methods in Iraq. I want, rather, to pose a question that is not articulated often enough: Do such acts of power work? Many believe that displays of military might are always erased or offset by countervailing forces of resistance. But those who are accustomed to the exercise of power know otherwise. They know that power can be used to redirect the forces of resistance.

It's a very nicely written opening, but is it still a relevant metaphor for the current situation? At best, this is a caution for Americans on the verge of war. In the conversation on the radio last night, Ghosh followed up by alluding to Gandhi, and reminding us that freedom can't be instilled at gunpoint. All of which was said, correctly, by many on the left in the build-up to war. But I don't think it's a useful sentiment two years later; some things have changed. Like the Democratic presidential candidates in the last election, we need to apply ourselves to the new reality; we cannot effectively 'run' against a war that has already happened. I believe that in some fundamental sense we have to find a way to accept the American occupation, though we can continue to draw attention to the potential for further exploitation of the Iraqi people.

How to read what is happening in Iraq today is a vexed question. It does seem that the new government is slowly establishing itself, and there are some hints that the insurgents are slowly being rounded up. Do we really believe that a stable Iraqi government can't survive the inevitable withdrawal of American forces? And would we still call then this an exercise in "Imperialism"? Since I do believe that US troops will withdraw in the next 2-3 years, I don't think the term is applicable in the territorial sense. The US will, admittedly, begin to demand economic privileges from the new Iraqi government with regards to access to oil, but that is an economic relationship. It's an exploitative relationship, and not a good thing for ordinary Iraqis (or, for that matter, for ordinary Americans). But we should employ a different word to describe it.

Getting back to India. Christopher Lydon asked me why there hasn't been more outrage about America's Iraq adventure in the postcolonial world.

What I said was, some Indians did in fact protest this war -- Ghosh's piece in the New Yorker certainly had an impact, for instance. But these days most of India's intellectuals are, correctly, more concerned with the problems that preoccupy India itself than they are with George Bush's latest follies. It's a classic American fallacy to think that everyone in the world is worried just about America!

What I should have said was something along these lines: there is in fact a great deal of diversity of thought in India about this war, and the best attitude for India to take in response. Some might see it as a naked display of American super-dominance on the geopolitical stage, built on lies, and a deeply corrupt enterprise from start to finish. (Oh wait, that's how I see it...) But others in India's new generation would take a more pragmatic stance: We weren't happy that you started this war, but now that you have, is there any way I can make money out of it?

On the radio, w/Amitav Ghosh

It looks like I am going to be on the radio on Monday, as part of an interview with Amitav Ghosh, on Radio Open Source, a new NPR show. It is scheduled for 7-8pm Eastern time (4-5am in India); I am supposed to be on between 7:20 and 7:35 or thereabouts.

They are only up in a few markets, including Boston, Seattle (Manorama, are you reading this?), and Salt Lake City (VK, are you reading this?). But apparently their shows are being both streamed and archived on the Internet, so you can listen remotely and later. Go to their blog to tune in.

Any suggestions for things to talk about on The Hungry Tide, or Amitav Ghosh more broadly? Apparently the producers of the show want to focus on what is happening in India today, politically and culturally -- not so much the literary aspect. Suits me just fine.

I'm going to be working on some questions of my own to ask Ghosh this weekend. But if you send me well-focused short questions that I can use I will try and give you credit over the air.

UPDATE: Ok, it's over. For those of you coming over from Open Source, here are two things I've written on Amitav Ghosh before:

1. On Tsunami relief

2. On The Hungry Tide

They are only up in a few markets, including Boston, Seattle (Manorama, are you reading this?), and Salt Lake City (VK, are you reading this?). But apparently their shows are being both streamed and archived on the Internet, so you can listen remotely and later. Go to their blog to tune in.

Any suggestions for things to talk about on The Hungry Tide, or Amitav Ghosh more broadly? Apparently the producers of the show want to focus on what is happening in India today, politically and culturally -- not so much the literary aspect. Suits me just fine.

I'm going to be working on some questions of my own to ask Ghosh this weekend. But if you send me well-focused short questions that I can use I will try and give you credit over the air.

UPDATE: Ok, it's over. For those of you coming over from Open Source, here are two things I've written on Amitav Ghosh before:

1. On Tsunami relief

2. On The Hungry Tide

Fusion Music: Sikhman/Rastaman and Hindi Reggaeton

Two interesting kinds of music fusion for you today.

1. Transglobal Underground, "The Sikhman & the Rasta," from Impossible Broadcasting. Transglobal Underground are a globalized dub/electronica outfit based in the UK. They've put out quite a number of CDs over more than 15 years, specializing in in experimental, often improbable, kinds of fusion. The results tend to be hit-or-miss. Every CD of their I have has one or two really interesting tracks, but there are also usually several "skips."

The song that caught my ear on the new CD Impossible Broadcasting is the one called "The Sikhman & the Rasta," in which an Afro-Caribbean dancehall MC called Tuup finds a link between Sikhs and Rastas ("The Rasta and the Sikhman dem don't cut hair/ The Rastaman and Sikhman dem have no fear") that is a bit eccentric, though there is something in it -- both Sikhs and Rastafarians have religious stipulations against cutting their hair. And both communities have a distinct and vibrant musical culture that is highly visible in the UK. This song is trying to cross-reference these two unique features.

Even if you don't see the connection, perhaps the song worth tracking down, if the free sample you can listen to at Emusic piques to your curiosity. All I can say is, I'm sure you don't already have anything in your MP3 collection that sounds like this.

2. Desi Reggaeton. Indian remixers in the New York area aggressively sample current hip hop hits on their "promotional" CDs. Most of the time, the remixes don't work very well -- do we realy need a remix of "Chaiya Chaiya" with the beat from "In da club"? Well, maybe you do. And every so often one comes across something that hits just right. Fortunately, the CDs tend to cost around $5, so if a CD is a dud it doesn't hurt too badly.

Some of the same problems are present on Bollywood High Volume 3: Reggaeton Edition, which exploits the current Reggaeton fad. The CD remixes songs from current Hindi films like Kaal, Tango Charlie, Waqt, and Mere Jeevan Saathi, with beats from Daddy Yankee, Tego Calderon, and Nina Sky. It's pretty entertaining to listen to, though as with Reggaeton generally (this fad is slated for extinction, don't you think?), it gets repetitive pretty quickly.

Desiqua. This CD is basically a DJ's fantasy. Unlike Chutney Soca in Trinidad, there isn't that much direct interaction between Indian music and Puerto Rican music going on, either in New York or in Puerto Rico.

However, there is actually a small but vibrant community of Indians living in Puerto Rico (we met a bunch of them the last time we were there). They and their New York expatriates call themselves "Desiquas" (Boriqua + Desi).

1. Transglobal Underground, "The Sikhman & the Rasta," from Impossible Broadcasting. Transglobal Underground are a globalized dub/electronica outfit based in the UK. They've put out quite a number of CDs over more than 15 years, specializing in in experimental, often improbable, kinds of fusion. The results tend to be hit-or-miss. Every CD of their I have has one or two really interesting tracks, but there are also usually several "skips."

The song that caught my ear on the new CD Impossible Broadcasting is the one called "The Sikhman & the Rasta," in which an Afro-Caribbean dancehall MC called Tuup finds a link between Sikhs and Rastas ("The Rasta and the Sikhman dem don't cut hair/ The Rastaman and Sikhman dem have no fear") that is a bit eccentric, though there is something in it -- both Sikhs and Rastafarians have religious stipulations against cutting their hair. And both communities have a distinct and vibrant musical culture that is highly visible in the UK. This song is trying to cross-reference these two unique features.

Even if you don't see the connection, perhaps the song worth tracking down, if the free sample you can listen to at Emusic piques to your curiosity. All I can say is, I'm sure you don't already have anything in your MP3 collection that sounds like this.

2. Desi Reggaeton. Indian remixers in the New York area aggressively sample current hip hop hits on their "promotional" CDs. Most of the time, the remixes don't work very well -- do we realy need a remix of "Chaiya Chaiya" with the beat from "In da club"? Well, maybe you do. And every so often one comes across something that hits just right. Fortunately, the CDs tend to cost around $5, so if a CD is a dud it doesn't hurt too badly.

Some of the same problems are present on Bollywood High Volume 3: Reggaeton Edition, which exploits the current Reggaeton fad. The CD remixes songs from current Hindi films like Kaal, Tango Charlie, Waqt, and Mere Jeevan Saathi, with beats from Daddy Yankee, Tego Calderon, and Nina Sky. It's pretty entertaining to listen to, though as with Reggaeton generally (this fad is slated for extinction, don't you think?), it gets repetitive pretty quickly.

Desiqua. This CD is basically a DJ's fantasy. Unlike Chutney Soca in Trinidad, there isn't that much direct interaction between Indian music and Puerto Rican music going on, either in New York or in Puerto Rico.

However, there is actually a small but vibrant community of Indians living in Puerto Rico (we met a bunch of them the last time we were there). They and their New York expatriates call themselves "Desiquas" (Boriqua + Desi).

Sudoku and Mathematics

[Source: Brainbashers. Solution below]

Everyone is talking about Sudoku, so I tried it and was, predictably perhaps, instantly addicted.

The Christian Science Monitor article sums up the game pretty nicely:

Sudoku, which means "single number" in Japanese, is essentially a simple logic problem with layers of hidden complexity that can draw the solver in to the point of obsession. A grid nine squares by nine is presented in which all the integers from 1 to 9 must appear in every row, every column and every 3-by-3 box. So far, so good.

Some numbers are given as initial clues. Then, by process of deduction, sometimes resorting to quite intense logical assumptions, the solver can slowly begin to work out what goes where.

There is a debate at Jabberwock about whether the skills involved in solving the puzzles are or aren't "math." A Financial Times article is referenced, only I don't subcribe to the FT, so I can't read it. It's a safe bet to say that the game requires intensive use of heuristic logic; perhaps it doesn't matter whether we use the "M" word or not.

The CSM article references two terms I hadn't seen before in connection with this question, in the following sentence:

Thus more committed fans will engage you in subtleties of bifurcation and Ariadne threads, of trial and error versus pure logic.

From a quick Googling, all I can get on "bifurcation" is some stuff Fractal algorithms, which doesn't seem at all relevant to Sudoku. And "Ariadne's thread," in mythology, was a gift Ariadne gave her lover to help him get through a labyrinth. In everyday usage, an "Ariadne thread" refers to a heuristic you use to help retrace a line of thought. Presumably in Sudoku it would relate to keeping track of a trail of hypotheticals or guesses. But again, I couldn't find anything that would explain what exactly the technical, mathematical reference point for "Ariadne Threads" might be. There is something going on with this in serious Computer Science-land, but I can't make heads or tails of it.

Update: There is some good math on Sudoku at Wikipedia, but this is more the way a computer would solve the grid as an "NP-Complete" problem, not so much a human.

For more on Sudoku, see of course Slate, Puzzle Cannon, and especially Locana.

Anand points to Web Sudoku, which might be a good place to get started if you're not looking to install the game software from Sudoku.com.

Ashes & Snow: A Traveling Circus

This spring, about half a dozen people, in separate instances, recommended that I see Ashes and Snow, an exhibition of photography by Gregory Colbert. It's at a "Nomadic Museum," a massive temporary building constructed out of storage containers, on Pier 54 in Chelsea. Judging by the hype and the marketing (I've seen posters for the exhibit up all over NYC), this has been the second "must-see" spectacle in New York this year. (The first being "The Gates," of course.)

The media and the blogosphere, as far as I can tell, have been very respectful of Ashes and Snow. Here is Kottke, and here is Richard's Notes (quite informative, actually). Even the excellent Tiffinbox, a professional photographer, seemed impressed with the idea of this exhibition.

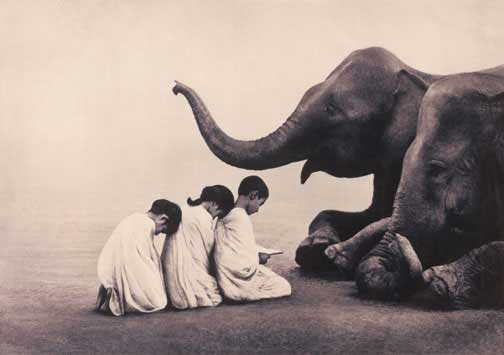

I was not impressed. I was, to begin with, bored by the photography, which isn't all that impressive visually; the sepia-tinted pictures are pretty, but the "ethereal" effects can be faked with Photoshop. More importantly, I was deeply annoyed by the strong undercurrent of exoticism and artificiality in the exhibit. Ashes and Snow is the Discovery Channel with one addition: exotic-looking Indian and Asian children in flowy robes are dancing and swimming placidly with the exotic (and often dangerou) animals. They don't speak, they don't smile, and they don't complain. They are, in a sense, analogous to the animals -- not just silent "native others," but, in the logic of this exhibit, animals themselves. The exhibit notes and the website will have you believe that it's a statement about "harmony between animals and human beings."

But I don't buy it, partly because of the blatant artificiality of the poses -- people don't just hang out with Cheetahs on stark desert plains. And they don't swim with elephants with their eyes closed, looking enraptured. (Or, as in the photo above, they don't sit in a row reading while elephants sit, apparently listening.) All of these are poses elaborately staged by the photographer, and it's hard for me to forget it. The other reason I can't buy the statement about human-animal unity is the manipulative environment of the gallery, which is memorably designed, to be sure (see this on Shigeru Ban's approach to "sustainable architecture"). But the deeply recessed lighting, the exotic world music in the background, the pebbles, the rice paper -- the whole presentation, in short -- plays up a "spiritual" and "exotic" atmosphere that nullifies any objective quality the photographs themselves might have.

If you watch the video loop at the back of the gallery for a bit, a male voice starts reciting this mantra while a desi chick dances in the mud with a baby elephant:

"Flesh to fire, fire to blood, blood to bone, bone to marrow, marrow to ashes, ashes to... snow."

To which my response is:

"Cow to beef, beef to burger, burger to mouth, mouth to stomach, stomach to shit, shit to... snow."

Ashes and Snow was for me the equivalent of a traveling circus, only in pictures. It's the traveling circus in an era of political correctness ("no animals were harmed," etc.), and World Music you can buy Starbucks. But it's still a circus, and still, to me, rather repulsive.

Next up for Ashes and Snow is apparently Los Angeles, where I am sure it will be received by more wildly appreciative crowds, dropping $12 per person. Better go, while the circus is still in town.

Rushdie on Creationism/Evolution

Rushdie has a piece in The Toronto Star on creationism vs. scientific atheism (via A&L Daily).

Though I don't actually agree with his point here (atheists should remain intolerant of religion, not accommodating), I admire the verve and style. Rushdie's recent novels seem a little tired... why doesn't he take this up full time?

Since I was just talking about this yesterday, let me quote the passage in the column where he talks about Intelligent Design:

Incidentally, is another winning Rushdie polemic about creationists in Step Across this Line. It is called "Darwin in Kansas."

Though I don't actually agree with his point here (atheists should remain intolerant of religion, not accommodating), I admire the verve and style. Rushdie's recent novels seem a little tired... why doesn't he take this up full time?

Since I was just talking about this yesterday, let me quote the passage in the column where he talks about Intelligent Design:

And in America, the battle over the teaching of intelligent design in U.S. schools is reaching crunch time, as the American Civil Liberties Union prepares to take on intelligent-design proponents in a Pennsylvania court.

It seems inconceivable that better behaviour on the part of the world's great scientists, of the sort that Ruse would prefer, would persuade these forces to back down.

Intelligent design, an idea designed backward so as to force the antique idea of a Creator upon the beauty of creation, is so thoroughly rooted in pseudoscience, so full of false logic, so easy to attack that a little rudeness seems called for.

Its advocates argue, for example, that the sheer complexity and perfection of cellular/molecular structures is inexplicable by gradual evolution.

However, the multiple parts of complex, interlocking biological systems do evolve together, gradually expanding and adapting — and, as Dawkins showed in The Blind Watchmaker: Why the Evidence of Evolution Reveals a Universe Without Design, natural selection is active at every step of this process.

But, as well as scientific arguments, there are others that are more, well, novelistic. What about bad design, for example? Was it really so intelligent to come up with the birth canal or the prostate gland?

Incidentally, is another winning Rushdie polemic about creationists in Step Across this Line. It is called "Darwin in Kansas."

Isaac Newton and Intelligent Design

For my book, I've been reading up a bit on the secularization of philosophy, which entailed some dabbling with the ideas of Isaac Newton, Blaise Pascal, Rene Descartes, and Baruch Spinoza. The road to a purely secular view of the world, it turns out, has had some interesting twists and turns. I've been particularly impressed by how much effort was exerted in the 17th century to hold onto the idea of "God"; nothing remotely similar is undertaken today.

All of the philosophers above were revolutionary mathematicians or scientists in addition to being philosophers. When they attempted to create linguistic and conceptual explanations of the world, they were also the first people to have understood certain aspects of the workings of the universe.

The best example of this might be Isaac Newton, who was the first to offer a comprehensive mathematical explanation of the planetary orbits in our solar system. When he looked at the solar system, he was probably the first to understand the true complexity of the physics involved, and it was dazzling.

Here is what he wrote in the Principia, in 1687:

It's beautiful, it all runs on its own with marvelous symmetry -- it must have been designed by something or someone Intelligent.

It so happened that I was reading this the day after I had read a piece on the pseudo-scientific movement called "Intelligent Design" in the New Yorker, and I was struck by the similarity in the reasoning.

Intelligent Design, as many readers know (especially those who look in on the excellent Pharyngula now and again), is a movement posing itself as an alternative theory (or set of theories) to evolution. According to Allen Orr in the article, its main scientific proponents are the biochemist Michael Behe, who wrote a book called Darwin's Black Box, and William Dembski, a mathematician.

Behe's arguments might relate to Newton the best. He believes the sheer complexity of individual cells, even of the simplest bacteria, is dazzling. In particular, he finds the interaction of different proteins that perform essential tasks in cells -- such as building the flagellum, or tail, or a bacteria, for example -- is "irreducibly complex." That is, each of the components is dependent on others in an extremely complex interlocking framework. It seems difficult to imagine how such a system might have evolved using Darwin's principle of natural selection, and indeed, apparently evolutionary biologists cannot yet fully explain it. And here is where Behe comes in:

There are, of course numerous very serious problems with this line of thought, and almost no professional scientists accept the "irreducible complexity" argument. I won't get into that here (read the article). Rather, what's interesting to me is that Behe's invocation of an "intelligence" is in response to a discovery every bit as dazzling as Newton's. There is an elegance to the workings of the natural world that, for these two men in very different eras and circumstances, seems impossible to accept as a purely unmotivated, random event.

The comparison ends there. Unlike Newton, Behe didn't discover anything in particular. And the complexity of proteins in cells has been known for several decades -- it's even taught in high school -- so it's hardly dazzling in the same way as the physics of the solar system must have been for Newton.

But most importantly, Newton's rationalization was part of a sweeping movement towards secularization that would soon see the idea of God considerably diminished in Philosophy. Within 60 years of Newton's invocation of a kind of Deist God in the Principia (i.e., who sets the machine in motion), there would be Denis Diderot in France, shrugging his shoulders: whether or not God does what Newton says he does doesn't matter to us, since the day-to-day workings of the world operate without divine intervention. Newton's "Intelligent Mechanick" God was not one to inspire fear and trembling, but rather a kind of cerebral -- and voluntary -- appreciation.

In contrast, the Intelligent Design of Behe and Dembski is in support of a belief in God that, for these scientists, resides in an emotional fundament that always trumps the scientific project.

The comparison, in the end, is small, but perhaps it is still worth considering. How do we explain the advent of dazzling complexity in the natural world? Do we depend on our own intelligence to decipher and describe the world, or do we posit the existence of of an Intelligent designer, who made it? I prefer the former, but I can understand how some smart people might not, under the right circumstances.

All of the philosophers above were revolutionary mathematicians or scientists in addition to being philosophers. When they attempted to create linguistic and conceptual explanations of the world, they were also the first people to have understood certain aspects of the workings of the universe.

The best example of this might be Isaac Newton, who was the first to offer a comprehensive mathematical explanation of the planetary orbits in our solar system. When he looked at the solar system, he was probably the first to understand the true complexity of the physics involved, and it was dazzling.

Here is what he wrote in the Principia, in 1687:

I do not think it explicable by mere natural causes but am forced to ascribe it to ye counsel and contrivance of a voluntary agent.' A month later he wrote to Bentley again: 'Gravity may put ye planets into motion but without ye divine power it could never put them into such a Circulating motion as they have about ye Sun, and therefore, for this as well as other reasons, I am compelled to ascribe ye frame of this Systeme to an intelligent Agent.' If, for example, the earth revolved on its axis at only one hundred miles per hour instead of one thousand miles per hour, night would ten times longer and the world would be too cold to sustain life; during the long day, the heat would shrivel all the vegetation. The Being which had contrived all this so perfectly had to be a supremely intelligent Mechanick.

It's beautiful, it all runs on its own with marvelous symmetry -- it must have been designed by something or someone Intelligent.

It so happened that I was reading this the day after I had read a piece on the pseudo-scientific movement called "Intelligent Design" in the New Yorker, and I was struck by the similarity in the reasoning.

Intelligent Design, as many readers know (especially those who look in on the excellent Pharyngula now and again), is a movement posing itself as an alternative theory (or set of theories) to evolution. According to Allen Orr in the article, its main scientific proponents are the biochemist Michael Behe, who wrote a book called Darwin's Black Box, and William Dembski, a mathematician.

Behe's arguments might relate to Newton the best. He believes the sheer complexity of individual cells, even of the simplest bacteria, is dazzling. In particular, he finds the interaction of different proteins that perform essential tasks in cells -- such as building the flagellum, or tail, or a bacteria, for example -- is "irreducibly complex." That is, each of the components is dependent on others in an extremely complex interlocking framework. It seems difficult to imagine how such a system might have evolved using Darwin's principle of natural selection, and indeed, apparently evolutionary biologists cannot yet fully explain it. And here is where Behe comes in: