Postcolonial/Global literature and film, Modernism, African American literature, and the Digital Humanities.

Trilling follow-ups

CNN: "Chapottymouth" on Wolfowitz

The other one, kind of more humorous, over at Chapotty Mystery (ph). And they're talking about -- they call it as the Wolfowitz turns. And they're talking about the "L.A. Times" nomination of Bono, the U2 frontman, as the head of the World Bank. In their eyes, he would be a good choice. And they said that would have the White House scared. And what they're saying is that Bono would have forgiven all loans to Africa or something. And in Wolfowitz, they found someone who won't just raise the interest rate, but he'll invade Africa.

Here's Sepoy's original post on the subject.

[Wait -- CNN is reading Chapati Mystery...? Someone should start a blog called "Tipu Sultan: Tiger of Mysore" just to get CNN reporters to pronounce "Tipu" and "Mysore":

"Tipu" --> "Typo"

"Mysore" --> "Eyesore" ]

I also liked Jon Stewart's quip yesterday that, given Wolfowitz's complete lack of qualifications for the presidency of the World Bank, the Bush administration seems to be essentially picking these guys alphabetically (Wolfenson--> Wolfowitz).

Uncyclopedia; You have two cows

It looks like Wikipedia, and is an actual Wiki. If I were feeling funny, I would add an entry or two. Or maybe expand the entry on India:

India is a software giant based in Toronto. The company achieved overnight success in 1986 when founder Al Gore invented the internet. Today, India is one of the largest companies in the world, with 1 billion employees and yearly profits of over $10.

Or I might add to the lucid comparisons of various political ideologies and world religions, under "You have two cows".

Interestingly, Wikipedia has an insightful entry on "You have two cows jokes" here. The highlight is this brilliant paragraph:

Because of their freedom and universality of topics, "two cows" jokes are sometimes considered a good example of "cross-cultural humor." They can be concise examples (not necessarily scientific) of how different cultures can express different visions of the same political concept, by paradox, hyperbole, or sarcasm. In practice, most such jokes reflect the views of outsiders to the systems being satirised. In the spirit of finding international common ground, some also see them as humorous manifestations of an underlying general scheme of political science that would compare legal or political concepts, such as the rights of ownership, across cultures around the world.

Has anyone published a paper on "You have two cows"? It seems like whoever authored this Wikipedia entry is itching to do so...

Voyeurism via Flickr: Other People's India Photos

Silk shop in Bombay:

Kanyakumari:

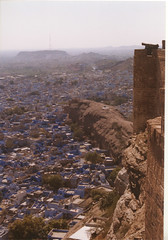

Jodhpur fort:

Srinigar-to-Lei:

In the Ellora caves:

From Bhaja Caves, near Pune:

Random guys at the Golden Temple, Amritsar:

I can't wait to go back to India this summer (I hope it works out...)

Do English and Hindi/Urdu hurt your ability to learn math?

Hindi and Urdu actually follow the English system, roughly, in having, non-transparent names for the 'teen' numbers (11-19), so if you follow this psychologist's argument, Hindi and English speaking children should have a tougher time understanding relationships between numbers in grades 1 and 2.

Thomason points out her many objections to the study, which all make sense to me. This seems like a very flawed study of an interesting issue.

My suggestion would be to experimentally teach one group of American first-graders a set of alternate names for 11-19, with new names that actually are transparent. Instead of 'eleven,' and 'twelve,' then, one could try 'teni-one' and 'teni-two'...

Then, compare their scores on a basic math test that only uses numerals (i.e., '11' and not 'eleven'). If there's anything in this theory, the 'teni-one' students should do somewhat better.

Something equivalent could be tried in Hindi: for one group of students, get rid of 'gyara,' 'bara,' etc. Replace with 'ek-das', 'bai-das', or something similar.

The World's Third Poorest Man

Still, I wonder: If the world's third-richest man is Indian, I feel pretty sure the world's third-poorest man is as well. And the second- and the poorest are probably his neighbours. In fact, I am also pretty sure I saw this third-poorest man yesterday, a sad figure in loose pants and nothing else who, for no clear reason, runs up and down the street near where I live.

You might want to read the whole thing.

Questioning "South Asia"

I like Manan's response to Nandy, but I have to say that I find some of the specifics Nandy's column a little questionable. Take, for instance, this sentence:

It [the term South Asia] has allowed the Indian state to hijack the right to the Indic civilisation, forcing other states in the region to seek new bases for their political cultures and disown crucial aspects of their cultural selves.

I see what he's getting at here (kind of), but the grammar is confusing. What does it mean to say that the state has "hijacked the right" to a civilization? I presume he's talking about the ongoing government interference in academic curriculum in India, but he never says that specifically anywhere in the column.

I think Nandy makes many interesting small points, but the bigger pieces of his argument don't hang together.

Blogaversary

It's been fun. I've sunk way more time into it than I intended to. I've made some new friends, and reconnected with many old ones. I've started to read the news in a different way; I'm better connected to what's happening out there. And best of all, the daily ritual of writing something for public consumption (however limited a public it is) has transformed the way I think about my writing.

There are things I could probably do better in terms of making this blog more user-friendly and more bloggy -- especially along the lines of opening up comments to anonymous commentors. I also definitely want to get the hell off Blogger sometime soon (maybe mid-May).

For right now I'm just going to focus on what I find most rewarding about blogging, and that is writing as well as I can about things that seem like they need to be talked about.

Thanks everyone.

Francis Fukuyama: The Protestant Ethic in an age of Islamic Terrorism

While Fukuyama's book was sharply criticized, its fundamental inspiration -- that with the universalization of liberal democracy, the Hegelian progress of History is effectively over -- was too powerful for the left simply to ignore. Fukuyama's soundbite was very influential even in its wrongness. (LINKS: The introduction to the book is online here; here is a summary in the conservative New Criterion magazine; and Wikipedia's summary is excellent).

So what is Fukuyama saying now? I just read Fukuyama's essay on Max Weber's Protestant Ethic in today's Times, and I can't find much to disagree with. This is a softer, smaller argument, one which will be much easier to digest than The End of History. While the characterization of Weber's theory as "Karl Marx on his head" at the beginning of its essay is a bit crude, from that point on Fukuyama's appraisal of Weber seems reasonable to me. Fukuyama's summary of Weber's argument, for instance, is clear and effective:

Weber's argument centered on ascetic Protestantism. He said that the Calvinist doctrine of predestination led believers to seek to demonstrate their elect status, which they did by engaging in commerce and worldly accumulation. In this way, Protestantism created a work ethic -- that is, the valuing of work for its own sake rather than for its results -- and demolished the older Aristotelian-Roman Catholic doctrine that one should acquire only as much wealth as one needed to live well. In addition, Protestantism admonished its believers to behave morally outside the boundaries of the family, which was crucial in creating a system of social trust.

* * * *

One suspects that Fukuyama, like many other free-market ideologues, is interested in Weber for ideological reasons: for him, "Islam" stands in for Communism as the antithesis of American democracy, secularism, and Protestant-ethic capitalism. If that is the case, shouldn't Weber have something helpfully explanatory to say about Why They Hate Us, and Why It Doesn't Matter Because We'll Always Win? Well, no, and Fukuyama himself points this out in his measured critique of Weber's culturalism:

It is safe to say that most contemporary economists do not take Weber's hypothesis, or any other culturalist theory of economic growth, seriously. Many maintain that culture is a residual category in which lazy social scientists take refuge when they can't develop a more rigorous theory. There is indeed reason to be cautious about using culture to explain economic and political outcomes. Weber's own writings on the other great world religions and their impact on modernization serve as warnings. His book ''The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism'' (1916) takes a very dim view of the prospects for economic development in Confucian China, whose culture, he remarks at one point, provides only slightly less of an obstacle to the emergence of modern capitalism than Japan's.

What held traditional China and Japan back, we now understand, was not culture, but stifling institutions, bad politics and misguided policies. Once these were fixed, both societies took off. Culture is only one of many factors that determine the success of a society. This is something to bear in mind when one hears assertions that the religion of Islam explains terrorism, the lack of democracy or other phenomena in the Middle East.

This is something I strongly agree with. In my experience people often turn to "it's just our culture" when they want to justify regressive political practices (there was a reference to this in the recent movie Swades...). And when looking at what is happening in, say, Iran, there is almost always a historical explanation that is far more concrete and in fact, actually explanatory than the deadening refrain of "it's just their culture/religion... they're incapable of doing otherwise." Culture (and "religion" as an effectiely synonymous sub-category) are cop-outs, whether we are talking about ourselves, or Those Poor Saps Over There.

As for the points Fukuyama makes in the second part of the essay regarding Weber's usefulness in thinking about public religion in the contemporary world, the jury is still out for me. Fukuyama alludes to the fact that Weber's assumption that religion would disappear under capitalism turns out to be wrong. I'm glad Fukuyama points out that this isn't just limited to the Islamic world, or other regions of the non-western world:

But it goes without saying that religion and religious passion are not dead, and not only because of Islamic militancy but also because of the global Protestant-evangelical upsurge that, in terms of sheer numbers, rivals fundamentalist Islam as a source of authentic religiosity. The revival of Hinduism among middle-class Indians, or the emergence of the Falun Gong movement in China, or the resurgence of Eastern Orthodoxy in Russia and other former Communist lands, or the continuing vibrancy of religion in America, suggests that secularization and rationalism are hardly the inevitable handmaidens of modernization.

Yes. People are perfectly capable of being modern, rational, and secular and also continue to express religious beliefs. And it's global: America proves this. India proves this. Turkey, under Erdogan, almost proves this.

That said, I do disagree with Fukuyama on whether "humanism," which according to Fukuyama is dominant in Europe after Christianity, carries some residual religious power:

Europeans may continue to use terms like "human rights" and "human dignity," which are rooted in the Christian values of their civilization, but few of them could give a coherent account of why they continue to believe in such things. The ghost of dead religious beliefs haunts Europe much more than it does America.

I don't see why that has to be the case. It's equally possible to describe humanism in terms completely dissociated from religious ethics. One gets suspicious whenever a historian says the word "haunted"; negative arguments are impossible to prove.

Pamuk on Istanbul

Conrad, Nabokov, Naipaul - these are writers known for having managed to migrate between languages, cultures, countries, continents, even civilisations. Their imaginations were fed by exile, a nourishment drawn not through roots but through rootlessness; mine, however, requires that I stay in the same city, on the same street, in the same house, gazing at the same view. Istanbul's fate is my fate: I am attached to this city because it has made me who I am.

Flaubert, who visited Istanbul 102 years before my birth, was struck by the variety of life in its teeming streets; in one of his letters he predicted that in a century's time it would be the capital of the world. The reverse came true: after the Ottoman empire collapsed, the world almost forgot that Istanbul existed. The city into which I was born was poorer, shabbier, and more isolated than it had ever been its 2,000-year history. For me it has always been a city of ruins and of end-of-empire melancholy.

Lionel Trilling: Criticism as the Pursuit of Complexity

From the democratic point of view, we must say that in a true democracy nothing should be done for the people. The writer who defines his audience by its limitations is indulging in the unforgivable arrogance. The writer must define his audience by its abilities, by its perfections, so far as he is gifted to conceive them. He does well, if he cannot see his right audience within immediate reach of his voice, to direct his words to his spiritual ancestors, or to posterity, or even, if need be, to a coterie. The writer serves his daemon [creative spirit] and his subject. And the democracy that does not know that the daemon and the subject must be served is not, in any ideal sense of the word, a democracy at all.

In short, there should be a place where people write, freely assuming their audience knows way more than the average reader of USA Today. Serious writers and thinkers should feel free to take advantage of such an intellectually enlivened -- if rarefied -- space to work out complex ideas. And if that means a few thousand readers a day rather than a few million, then so be it. The circulation of your magazine (or today, your hitcount) is not everything; if it is, you're probably not doing your best thinking.

This idea of the writer's "daemon" or "daimon" (which is not the same as "demon," in case anyone is confused) is one that Trilling comes back to in various ways in many other essays. I notice it, for instance, in Trilling's "T.S. Eliot's Politics" (1940) in which his general purpose is to review Eliot's rather less-than-inspiring book, Christianity and Culture:

What the philosophy of the [French] Revolution lacked or denied it is difficult to find a name for. Sometimes it gets called mysticism, but it is not mysticism and Wordsworth is not a mystic. Sometimes, as if by a kind of compromise, it gets called "mystery," but that, though perhaps closer, is certainly not close enough. What is meant negatively is that man cannot be comprehended in a formula; what is mean positively is the sense of complication and possibility, of surprise, intensification, variety, unfoldment, worth. These are things whose more or less abstract expressions we recognize in the arts; in our inability to give this quality a name, our embarrassment, even, when we speak of it, marks a failure in our thought. But Wordsworth was able to speak of this quality and he involved it integrally with morality and all the qualities of mind which morality suggests.

In the lines just before this passage, Trilling has been talking about Wordsworth's turn against the radical politics of the French Revolution during the Reign of Terror as a possible model for Eliot, in the latter's antagonistic relationship with the Anglo-American left in the 1930s. I read Trilling here as saying that what Wordsworth wanted to do was use art to think about things that are too complicated (which could also mean: too personal, too mysterious, too dynamic) to be represented via any available political or ideological system. Trilling would equally value the pursuit of complexity to anyone engaged in artistic creation or serious criticism of the arts. Thus, it's no surprise to see almost exactly the same sentences at the end of the preface to The Liberal Imagination:

It is one of the tendencies of liberalism to simplify, and this tendency is natural in view of the effort which liberalism makes to organize the elements of life ian a rational way. And when we approach liberalism in a critical spirit, we shall fail in critical completeness if we do not take into account the value and necessity of its organizational impulse. But at the same time we must understand that organization means delegation, and agencies, and bureaus, and technicians, and that the ideas that can survive delegation, that can be passed on to agencies and bureaus and technicians, incline to be ideas of a certain kind of a certain simplicity: they give up something of their largeness and modulation and complexity in order to survive. The lively sense of contingency and possibility, and of those exceptions to the rule which may be the beginning of the end of the rule--this sense does not suit well with the impulse to organization. So that when we come to look at liberalism in a critical spirit, we have to expect that there will be a discrepancy between what I have called the primal imagination of liberalism and its present particular imagination. The job of criticism would seem to be, then, to recall liberalism to its first essential imagination of variousness and possibility, which implies the awareness of complexity and difficulty.The gestures Trilling is making in the two passages quoted above are not the same, but they do rhyme. In one place, Trilling is asking his readers to take T.S. Eliot's conservatism seriously, by substituting Wordsworth's turn away from radicalism for Eliot's. He uses the example of Wordsworth's prodigious poetic output as proof of the value of the endeavor. In the second instance, Trilling suggests that it is the role of criticism to go against the utilitarian tide -- the dominant stream of technicians, explainers, and by extension to our own day, the shallow ideas that can be presented on Television in a minute or two (or on Internet weblogs in a meme or two). Criticism, he hopes, will be a space where people can think about things that may not necessarily go anywhere, where transparent use-value is not quite the goal.

In both essays, it's important to note that Trilling -- a life-long New York liberal, of Jewish descent -- is in some sense praising his enemies. (With Eliot, that might have been especially difficult to do, given the circumstances.) His essay on Eliot is Trilling demonstratively respecting Eliot's ideas, even though he feels Eliot's argument doesn't quite work. And in the essay on liberalism, Trilling spends quite a number of pages praising John Stuart Mill (an early 19th century liberal, and one of the architects of 19th century philosophy of utilitarianism) for praising Coleridge's Establishment conservatism. Trilling reads Mill's generosity to Coleridge as a model for what he himself should do.

The political modulation (which in our current political idiom might be called "waffling") is important because it makes Trilling's emphasis on "complexity" either suspect or especially noble, depending on your perspective. "Complexity" in the two instances is shown by the refusal to tear down one's enemy, to respect the Conservatives in Liberalism's (dominant) midst. Without this necessary nuance, "complexity" is actually a bit too simple an idea to be interesting. With it, the connection between a kind of intellectual discipline to a humanist ethical imperative becomes clear.

Marketing India to Foreign Tourists

T. Thomas is brainstorming some ways to improve India's cachet as a tourist destination. Despite experiencing some big changes over the past 15-20 years, India remains a place that few people visit -- only about 3 million visitors a year, to Thailand's 20 million. And many who do go there aren't especially impressed -- dirt, heat, and crowds are still things that are experienced by many western tourists as a turn-off. Everyone likes looking at the Taj Mahal, but no one like going to the Taj Mahal! There's no easy way to solve it -- the heat and the crowds certainly aren't going anywhere (though heat can be an attraction, especially to people from cold places) -- but T. Thomas has some good ideas.

Fortunately, in my opinion, we as a nation have become confident enough in our own standing and achievements that we can rise above anti-colonial feelings and talk about the colonial period without inhibitions or resentment. Although the Mughals colonised India and even converted our people to their religion four centuries ago, today we take pride in showing tourists monuments like the Taj Mahal as the pride of India. With the passage of time, the same is happening to the monuments and cities built by our European colonisers -- the Portuguese, the Dutch, the French, and the British. For a European tourist it is often more interesting to see remnants of the adventurers from their own countries. Even for the Americans, it is easier to relate to such sites as most of them are descendants of Europeans.

Fortunately, we have several such monuments and sites bearing witness to the history of our European colonisers. We should use them to market our country. Take Pondicherry. It has several French remnants, including the use of the French language. In France schoolchildren are still taught about the French empire in India, which consisted of Pondicherry, Mahe, Karaikkal, and Chandannagar.

I think he's right on the money here. Everyone goes to Churchgate, but no one really talks about why it was built, or what happened there. And: last summer we went to the beach in Bandra (near the Taj Land's End Hotel), where one finds strange ruins with Portuguese inscriptions on them -- remnants of a fort. But the plaques at the site don't explain very much. What do the Portuguese inscriptions mean? What was life like for the Portuguese who lived in this fort? What is the historical value of these particular ruins? Are there other such forts along the coastline? I was a little disappointed to find that no one there seemed to know very much. (This website has some information about the Portuguese "North Provinces," but nothing specifically about that particular fort.

An example of a book that does something along these lines is Krishna Dutta's Calcutta, which is a kind of Travel Guide for History Wonks. I picked it up last year in Amherst, Massachusetts (of all places)... More books like these could do wonders for India's reputation as a "colonial tourism" destination.

Certainly, when it comes to Bombay, Delhi, and Calcutta there is lots to work with in terms of celebrating (rather than shunning) British architectural achievements, as well as key moments in British colonial history. I believe it is possible to do this critically and educationally -- without succumbing to what Rushdie called "Raj Nostalgia."

The trick might be to find "colonial" tourist attractions that are a little off the beaten path... A few months ago I remember reading somewhere that George Orwell's birthplace is in the town of Motihari, in Bihar, and is essentially unmarked (read this interesting account of one visitor's experience there). Why? Finally, I have to disagree with T. Thomas on one point, and that is the desirability of younger, less wealthy tourists -- the backpackers. His plan is to lure in European and Japanese retirees, who have money to spend and time to kill:

These are usually people who have retired and can afford to explore the world outside their own immediate reach. The younger backpackers or student-type tourists are not sufficiently well funded. Therefore, they are not our primary target group although they should also be encouraged and welcomed to this country as they can be our brand ambassadors to the older generations of their countrymen and one day when they can afford it, they may come back with their own families.

I'm glad he softens his line towards the end, but I think he's probably underestimating how much money the average backpacker really has to spend. Certainly, some tourists (mainly Europeans) come to India because it's cheap -- you can stay at a hostel-y type of place for Rs. 100 ($2 USD) a night, even in tourist towns. Others are looking for these types of bargains, but in fact they are still carrying Daddy's Credit Card with them, and often end up spending a fair bit while traveling after all. Backpackers might stay in cheap hostels or "non guidebook" hotels, and eat relatively cheaply. But they are nevertheless highly likely to shell out Rs. 5000 or more on a plane ticket to get to someplace fast (Indians, in contrast, tend to take the train), and then buy a rather pricy Kashmiri shawl or art-work to take back with them to Sweden. So to T. Thomas I say: don't underestimate the backpackers! They might not look like much, but they're trying not to look like much. They are still loaded, and should be included in the proposed Scheme to Sell India.

Tourism is a business based partly on the availability of leisure (sun, beaches, mountains to climb, food to taste, stuff to buy, etc.). But these days it is also potentially enabled by opportunities to learn -- about history, culture, religion, or the environment. Some of these might seem distasteful to some, but it's quite possible to self-consciously "exploit" one's geo-historical heritage tastefully. And by this point in history, the histories of British, French, and Portuguese colonialism in India ought to be far more interesting as a selling point to potential British, French, and Portuguese tourists than as a source of angst for Indians themselves.

One way to balance historical tourism of the sort I've been describing might be to attach it to important sites in the freedom struggle. Places where Gandhi did something interesting... that sort of thing. (The latter might appeal to NRI tourists in particular.)

The Rza

He talks about the "de-tuned" (discordant) piano sample that is such a trademark of the early Wu-Tang records, his own records (under the Rza alias), and finally the Ghost Dog soundtrack. (Rza also did Kill Bill: Volume 1, but they discussed that in an earlier interview.)

He also explains his various aliases: "Prince Rakeem" (early days), "Rza" (1992-1997), and "Bobby Digital" (1997-2000 or so). The turn to militancy and self-discipline in the middle phase explains how it was possible for him to be so prolific for a period. And the turn back to a 'party' persona also explains why he hasn't done anything comparable since then.

The most interesting part for music heads will be the first 15 minutes. The most interesting part from a biographical perspective is the last 10-15 minutes, when Rza and Terry talk about ODB (who was actually Rza's cousin), and how growing up poor makes it impossible to ever really experience childhood.

A Conference on the Tsunami at Columbia's SIPA

I missed the morning panel on the seismic impact of the Tsunami. However, I did come across this article at the Guardian, which discusses it.

Afshan Khan, of UNICEF, gave the keynote address, highlighting her organization's efforts to assist children affected by the Tsunami. She made the point that in many of the affected areas, there were severe problems in terms of security and quality of life even before the Tsunami. One example is the water supply, which was talked about as a concern after the Tsunami wave left salt in fresh water sources. In many places in Southeast Asia, there were severe problems in the water supply even before the Tsunami.

Another issue much talked about in the coverage of the Tsunami was the danger that recently-orphaned children might be abducted by child-traffickers. Khan argued that this isn't as big a problem as has been reported, largely because many of the children who lost parents are being looked after by extended family. Moreover, there were significant problems in the trafficking of children all throughout Southeast Asia before the Tsunami as well.

Vector-borne diseases. One of the morning speakers alluded to the relief that many aid workers have felt that the explosion in diseases like malaria, cholera, and Denge fever, which the WHO had predicted soon after the Tsunami hit, have not materialized. With malaria, the Tsunami actually helped to slow the disease, as mosquitoes can't breed in brackish water. (See this link at Tsunami Help)

Khan added that here, as with water and child protection, there are actually opportunities to "leverage up" the quality of living in the wake of the Tsunami. That is to say, the influx of aid money and the current attention on the above problems can be an opportunity to raise standards to a level above where they were before the tsunami. Khan gave examples on how this might work with regard to fighting vector-born diseases (she mentioned the increased use of bed-nets). But she didn't say much about how this "leverage up" strategy might work in terms of fighting child-trafficking in particular.

Another speaker whose presentation I found interesting was Anne Marie Murphy, of Seton Hall University (no home page, but she's quoted here). She talked about how the domestic political situation in Indonesia has affected their government's response. The Indonesians have set a three-month deadline for NGO aid workers, as well as groups such as the UNHCR, to leave Aceh. (See the Jakarta Post)

She also explained some of the particulars of the conflict between the Indonesian government and the rebels in Aceh province. The rebel fighters (the "Free Aceh Movement" or "GAM") started an insurgency in 1976. After Suharto's government fell in 1998, the GAM and the TNI had come close to signing a peace deal; a senior general had even gone to the province to apologize for earlier military-sponsored atrocities in the region. In the Indonesian media, there was quite a bit of sympathy for the Acehnese. But the progress of that peace was derailed by the events in East Timor in 1999. Following the failure of the referendum-strategy, the government was reluctant to make any compromises with a separatist movement that might lead to any further secessions. In 2003, the fragile peace collapsed, and the government again declared martial law. Things were as bad as ever when the Tsunami hit in December, but the two sides signed a provisional truce in the wake of the disaster. (The truce is now in danger of falling apart again, as this report shows.)

Corruption in the Indonesian military. According to Murphy, there are some elements in the Indonesian military that would like to see the conflict continue. According to her information, only 30% of the military's budget comes from the state. The rest comes from "military businesses" and illict activities like smugggling. The generals have a free hand in "military operations areas" like Aceh, and therefore they have an interest in keeping the conflict going. Indonesia is one of the most corrupt (or to put it in a more friendly way, "least official") economies in the world, and this is going to be a huge problem for brokering a more stable social and political environment in Aceh, irrespective of the progress of Tsunami relief and rehabilitation.

On the same panel, I was interested in what Sreenath Sreenivasan had to say about the Indian government's hesitation about receiving aid at a time when it wants to establish itself as a regional power. Sreenivasan pointed out that the Indian military played a major role in providing assistance in the immediate aftermath of the Tsunami. An Indian navy hospital was in Sri Lanka within a few hours of the Tsunami, delivering medicines. In contrast, the U.S.S. Duluth didn't arrive in Sri Lanka until January 10. When the U.S. Navy came, however, they made sure the cameras were rolling... Perhaps India has to do more PR internationally to ensure that its good works are noted by the international media.

Sreenivasan lamented that the "self-sufficiency" of South Asia as a region isn't widely recognized. He alluded to this article in the Globalist, by Ashutosh Sheshablaya, on the "Great Indian Absence" from the relief story.

Finally, Sreenivasan pointed out that in international disasters, there is often a gap between the amount of money that is donated, and the amount of money that can actually be spent, due to human and organizational limitations. After the devastating Hurricane in 1998 ("Hurrican Mitch"), US $1 billion was pledged, but only $200 million spent. After the earthquake in Iran in 2003, again, $1 billion was pledged, but this time only $20 million spent! An unprecedented $4 billion has been pledged for the Tsunami relief effort. It is an open question whether it will be humanly possible for all that money to be used quickly.

As a side note, Sreenivasan mentioned that he had recently met with the Sri Lankan parents of "Baby 81". The parents of the baby and the baby himself (Abhilash) were recently brought to the U.S. by the Good Morning America TV show as a "symbol of hope." Sreenivasan's wife had served as a translator, and he was able to talk with the parents and get their side of the story. Apparently, the father, who lost his barbershop business in Sri Lanka, had borrowed a lot of money to rebuild his shop. He had accepted the American offer to visit the U.S. partly because he wanted to try and raise money to pay back the debt. The amount he owes: $600.

And just a few small comments on the media panel. The question the panel was asking -- did the mainstream media do a good job covering the Tsunami? -- seems to me to be somewhat unanswerable, at least as long as the role of the media in covering disasters remains a little unclear. Should the media be merely reporting events dispassionately, or should it use the dissemination of information to raise awareness with an explicitly moral, humanitarian aim? The other unanswerable question is whether readers should dictate the shape and scope of the news, or whether that responsibility lies with editors and journalists. The journalists on the panel argued that the limitations in the western media's coverage of the Tsunami (one thinks of the inordinate coverage of the supermodel who was stuck in a tree in Phuket) are a function of the audience.

Suleman Din, one of the panelists, is a journalist for the Newark Star-Ledger, who normally covers the "desi NJ" beat. But after the Tsunami he was sent to Sri Lanka, where he filed a series of groundbreaking reports. The Star-Ledger's archives require payment, but I came across a couple of his Tsunami pieces here, and here.

Born Into Brothels: Ethical Questions, and Links

We finally saw Born Into Brothels last night. The documentary won an Oscar last week, but it will never be shown in India, apparently to protect the identities of the mothers of the children in the film.

There have been some complaints about the film's negativity, but I think it's fair to dismiss those. Though the filmmakers are clearly making Born Into Brothels with an ethical and humanitarian goal in mind (i.e., help keep these kids out of the life of prostitution and crime that seems to be their fate), it's not a protest film or an "exploitation" film. These are the children of prostitutes, living in a notorious neighborhood in Calcutta, but remarkably, there are no scenes of violence against them or explicit sexuality around them in the film. (There is one scene with implied violence, which also features a string of the most aggressive Bengali curse-words imaginable, but it only lasts a few seconds). Instead, the film focuses on the mundane aspects of their lives, and of course on photography -- which is often quietly remarkable (as the above image shows).

One of the interpreters Briski worked with has also complained about the film:

Meanwhile, the documentary has had its share of controversies. It has "ethical and stylistic" problems, says Partha Banerjee, interpreter between the filmmakers and the children. He has reportedly written to the Academy Of Motion Picture Arts And Sciences, complaining that the children's lives had worsened. Authorities at Sabera Foundation's home, where some of the children live, said other kids didn't know about their Sonagachhi connection. Now, the award has brought the kids into global prominence.(link)

The fact that the lives of some of the children worsened doesn't surprise me. Briski is quite clear that her goal isn't to extract the kids, or save them at any cost. Rather, she wants to help them help themselves, without severing them from their families or their surroundings. With that goal and that methodology, it's virtually inevitable that there will be some failures.

One can also justify the film along a "greatest good" argument. Some good will come from the money that the sale of the children's photographs has presumably raised, as well as from the revenue from the film, and even from funds sent in by viewers of the film who see it and want to help. Briski has already started a school. It's possible that the lives of many more kids than just these seven or eight will be helped by what she started.

And finally, many of the American reviewers had issues with the film's tone. Here I have to concede they have a point. Briski tries hard to ensure that this isn't a movie about herself (i.e., as a saint), and also not a voyeuristic "look at how miserable these kids are" affair. The result is a film with an approach I haven't seen before. It's original -- and that, more than anything else, is why it probably deserved the Oscar -- but it sometimes seems a little unsure of what it's trying to do.

* * * * *

Some links

A commentor on Tiffinbox posted some additional links about the film, including the site Kids With Cameras, which many other blogs have linked to:

It leaves out, for instance, the work of many other photographers who have introduced young people who have few worldy prospects to a new life by introducing them to photography.

Shahidul Alam and his colleages have worked for eight years with a group of young photographers who call themselves Out of Focus. (link).

Nancy McGirr teaches photography to children who worked in a garbage dump in Guatemala. (link. Also here)

And Zana Briski is doing her best to make her work in Kolkata more than a one-time event. She started Kids With Cameras (link)

to send other photographers to countries around the world to train children to become photographers. Gigi Cohen (whoalso has worked with Child Labor & the Global Village) is currently in Haiti.

And Ms. Musings links to an NPR interview with Briski the day after she won the Oscar.

UPDATE: See Shashwati Talukdar's response to the nasty review in Outlook.